Elevated calprotectin levels are associated with mortality in patients with acute decompensation of liver cirrhosis

Camila Matiollo, Elayne Cristina de Morais Rateke, Emerita Quintina de Andrade Moura, Michelle Andrigueti,Fernanda Cristina de Augustinho, Tamara Liana Zocche, Telma Erotides Silva, Lenyta Oliveira Gomes, Mareni Rocha Farias, Janaina Luz Narciso-Schiavon, Leonardo Lucca Schiavon

Abstract

BACKGROUND

Acute decompensation (AD) of cirrhosis is related to systemic inflammation and elevated circulating cytokines. In this context, biomarkers of inflammation, such as calprotectin, may be of prognostic value.

AIM

To evaluate serum calprotectin levels in patients hospitalized for complications of cirrhosis.

METHODS

This is a prospective cohort study that included 200 subjects hospitalized for complications of cirrhosis, 20 outpatients with stable cirrhosis, and 20 healthy controls. Serum calprotectin was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay.

RESULTS

Calprotectin levels were higher among groups with cirrhosis when compared to healthy controls. Higher median calprotectin was related to Child-Pugh C, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy. Higher calprotectin was related to acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) and infection in the bivariate, but not in multivariate analysis. Calprotectin was not associated with survival among patients with ACLF; however, in patients with AD without ACLF, higher calprotectin was associated with a lower 30-d survival, even after adjustment for chronic liver failure-consortium (CLIF-C) AD score. A high-risk group (CLIF-C AD score ≥ 60 and calprotectin ≥ 580 ng/mL) was identified, which had a 30-d survival (27.3%) similar to that of patients with grade 3 ACLF (23.3%).

CONCLUSION

Serum calprotectin is associated with prognosis in patients with AD without ACLF and may be useful in clinical practice to early identify patients with a very low short-term survival.

Key Words: Inflammation; Liver cirrhosis; Acute-on-chronic liver failure

INTRODUCTION

Cirrhosis is characterized by fibrosis and nodule formation of the liver, secondary to different mechanisms of liver injury that lead to chronic necroinflammation[1]. The natural history of cirrhosis is usually marked by a long-lasting compensated phase, followed by a decompensated stage characterized by the occurrence of complications such as ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and gastrointestinal bleeding related to portal hypertension[2]. Parallel to worsening liver function and progression of portal hypertension, there is a derangement in the immune system denominated as cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction (CAID). CAID is a complication associated with a dynamic coexistence of both acquired immunodeficiency, which contributes to the high rate of infection in patients with decompensated cirrhosis, and systemic inflammation, which may exacerbate the clinical manifestations of cirrhosis, such as hemodynamic changes and kidney injury[3,4].

Systemic inflammation is a consequence of persistent and inadequate stimulation of immune system cells. Advanced cirrhosis, particularly decompensated disease, is associated with increasing disorders of gut homeostasis, including changes in microbiota, reduced motility, bacterial overgrowth, and increased intestinal permeability[5]. These factors intensify the systemic exposure to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) from intestinal microorganisms and their products, which provides chronic stimulation of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), expressed on innate immune cells[3,4]. In addition, systemic inflammation can occur in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) even in the absence of bacterial infections due to the release of damaged liver damageassociated molecular patterns (DAMPs)[6]. Knowing the characteristics of the immune system of patients with cirrhosis is important for understanding and developing new diagnostic and therapeutic tools that reduce morbidity and mortality in these patients.

Calprotectin is a heterodimeric complex composed by S100A8 and S100A9 proteins, also called MRP8 and MRP14, or calgranulin A and B, respectively[7]. Calprotectin is found in neutrophils and monocytes, accounting for 60% of the cytosolic protein content of neutrophils[8]. Due to its high stability in biological fluids, calprotectin can be used in clinical practice as a marker of neutrophil activity in several chronic inflammatory diseases, infections, and cancer[7]. Fecal concentrations of calprotectin are well established in clinical practice to differentiate irritable bowel syndrome from inflammatory bowel disease and to monitor disease activity in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis[8]. Circulating calpro-tectin levels, although less studied, were reported to be related to the presence of cirrhosis and severity of liver dysfunction[9,10]. However, these preliminary small studies focused on alcohol-induced liver disease and were mainly comprised by patients outside the context of acute decompensation (AD)[9,10]. Hence, we aimed to evaluate circulating calprotectin in patients hospitalized for AD of cirrhosis, investigating its prognostic significance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

This study is part of a project that aimed to follow a cohort of adult patients (≥ 18 years of age) admitted to the emergency room of a Brazilian tertiary hospital due to AD of liver cirrhosis. Details about the methodology were previously published[11] and are briefly presented below.

Consecutive subjects admitted to the emergency room for AD of cirrhosis between January 2015 and September 2018 were evaluated for inclusion. The exclusion criteria were: Hospitalization for elective procedures; hospitalization not related to complications of liver cirrhosis; hepatocellular carcinoma outside Milan criteria; severe extrahepatic disease; inflammatory bowel disease; inflammatory rheumatic disorders (such as psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and ankylosing spondyloarthritis); extrahepatic malignancy; and use of immunosuppressive drugs.

The diagnosis of cirrhosis was established either histologically (when available) or by combination of clinical, imaging, and laboratory findings in patients with evidence of portal hypertension. AD was defined by acute development of hepatic encephalopathy, large ascites, gastrointestinal bleeding, bacterial infection, or any combination of these.

Twenty healthy individuals evaluated during routine laboratory tests and 20 patients with stable cirrhosis followed at our outpatient clinic served as control groups. Details about the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the control groups were previously published[12] and are available at Supplementary material and methods.

The study protocol complies with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee on Human Research of the Federal University of Santa Catarina.

Methods

Patients were evaluated within 24 h of admission by one of the researchers involved in the study. They were followed during their hospital stay and 30-d mortality was evaluated by phone call in case of hospital discharge. In case of more than one hospital admission during the study period, only the most recent hospitalization was considered.

Active alcoholism was defined as an average overall consumption of 21 or more drinks per week for men and 14 or more drinks per week for women during the 4 wk before enrolment (one standard drink is equal to 12 g absolute alcohol)[13]. All patients admitted for AD of cirrhosis in our institution are actively screened for bacterial infections. A diagnostic paracentesis was performed in all patients with ascites at admission. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) was diagnosed when the neutrophil count in the ascitic fluid was ≥ 250 neutrophils/mm3in the absence of intra-abdominal source of infection, regardless of negative culture[14]. Hepatic encephalopathy was graded according to West-Haven criteria[15] and, if it was present, a precipitant event was actively investigated and lactulose was initiated and the dose adjusted as needed. All subjects with acute variceal bleeding received intravenous octreotide and an antibiotic (intravenous ceftriaxone) and underwent urgent therapeutic endoscopy after stabilization. Severity of liver disease was estimated using the Child-Pugh classification system[16] and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD)[17] calculated based on laboratory tests performed at admission. ACLF, chronic liver failure (CLIF)-sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA), and CLIF-consortium (CLIF-C) AD scores were defined as proposed by the European Association for the Study of the Liver-Chronic Liver Failure Consortium[18,19].

Serum calprotectin levels

Blood samples were obtained within 24 h following hospitalization (inpatients) and after medical evaluation (outpatients). Peripheral blood samples were centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 min at room temperature within 1 h following collection. Serum samples were then aliquoted and stored at -80 °C until analysis. Serum calprotectin levels were measured using a commercial quantitative sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay kit (FineTest, REF EH4140, Wuhan, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All measurements were performed in duplicates. Results were determined from a standard curve carried out from six human calprotectin standards, with a lower detection threshold of 15.625 ng/mL.

Statistical analysis

The normality of variable distribution was determined by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The correlation between numerical variables was evaluated using Spearman’s correlation coefficient. Continuous variables were compared using the Student’s t-test in case of a normal distribution or Mann-Whitney test in the remaining cases. Categorical variables were evaluated by the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to explore factors independently associated with ACLF and infection. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed to investigate the relationship between variables of interest and survival. The best cutoffs of calprotectin for predicting mortality were chosen based on the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves. Survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and survival differences between groups were compared using a log-rank test. All tests were performed using SPSS software, version 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States). A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics and assessment of calprotectin levels according to study group

Two hundred and forty patients were involved in this research: 200 subjects admitted for AD, 20 individuals with stable cirrhosis, and 20 healthy controls. Age and gender were similar across the study groups. The main characteristics of the two groups with cirrhosis are depicted in Table 1. In hospitalized patients, the mean age was 57.29 ± 11.56 years and 71.5% were male. The most frequent etiology of cirrhosis was alcohol (53.0%), followed by hepatitis C (29.0%) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (12.6%). Hospitalized subjects were mainly categorized as Child-Pugh C (45.5%) and the mean MELD score was 17.6 ± 7.0.

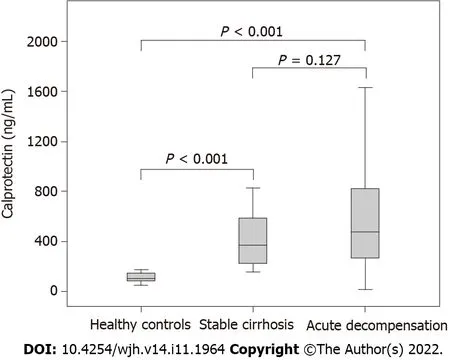

Figure 1 shows the levels of calprotectin according to the study group. No significant difference in circulating calprotectin was noted when hospitalized patients were compared to the stable cirrhosis group (477.2 ng/mL vs 369.5 ng/mL, P = 0.127). However, healthy subjects showed significantly lower calprotectin levels as compared to subjects hospitalized for AD (98.88 ng/mL vs 477.2 ng/mL, P < 0.001) and outpatients with stable cirrhosis (98.88 ng/mL vs 369.5 ng/mL, P < 0.001).

Factors associated with calprotectin levels in hospitalized cirrhotic patients

No significant correlations were observed between calprotectin levels and numerical variables studied (Supplementary Table 1).

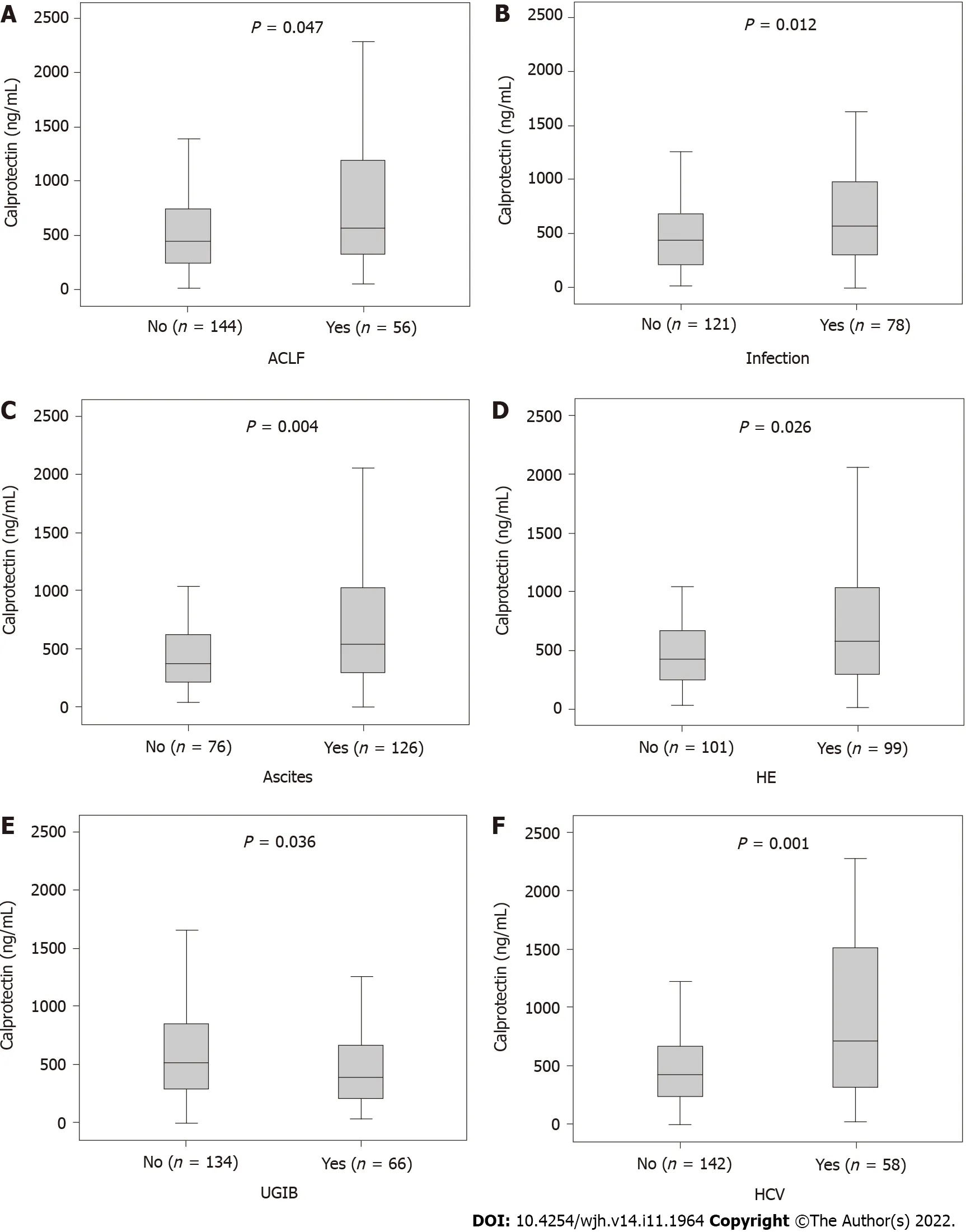

Male patients had higher serum calprotectin levels (530.5 vs 368.2 ng/mL, P = 0.015). When calprotectin concentrations were evaluated according to the presence of specific complications, significantly higher median values were observed among patients with ACLF (577.8 vs 453.3 ng/mL, P = 0.047), infection within the first 48 h (581.3 vs 446.5 ng/mL; P = 0.012), ascites (552.7 vs 385.9 ng/mL; P = 0.004), and hepatic encephalopathy (581.3 vs 428.1 ng/mL; P = 0.026) (Figure 2A-D). On the other hand, significantly lower median values were observed among patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) (401.4 vs 532.4 ng/mL; P = 0.036) (Figure 2E). Median calprotectin levels were similar regardless of the diagnosis of acute alcoholic hepatitis (475.8 vs 478.6 ng/mL; P = 0.964) or alcoholic liver disease as a cause of cirrhosis (512.7 vs 450.6 ng/mL; P = 0.118). Patients with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis had higher serum calprotectin concentrations (716.5 vs 427.8 ng/mL, P = 0.001) (Figure 2F). No differences were observed regarding other causes of cirrhosis.

Figure 1 Box plot of serum calprotectin levels among healthy controls, stable cirrhostics, and hospitalized cirrhotics with acute decompensation. The line across the box indicates the median value; the box contains the 25% to 75% interquartile range; and the whiskers represent the highest and the lower values. There were no differences in calprotectin levels between patients with acute decompensation and stable cirrhosis patients (P = 0.127).Significantly lower calprotectin levels were observed among healthy controls compared to stable cirrhosis (P < 0.001) and patients with acute decompensation (P <0.001).

Serum calprotectin concentrations were higher in Child-Pugh C patients compared with Child-Pugh A (586.4 ng/mL vs 313.8 ng/mL, P = 0.006) and Child-Pugh B (586.4 ng/mL vs 406.7 ng/mL, P = 0.002). There was no difference in calprotectin concentrations between Child-Pugh A and B patients (313.8 ng/mL vs 406.7 ng/mL, P = 0.163).

Calprotectin levels according to the presence of ACLF or infection in patients admitted for complications of cirrhosis

Variables related to ACLF are exhibited in Supplementary Table 2. ACLF at admission was associated with higher calprotectin levels in the bivariate analysis (577.75 vs 453.05 ng/mL, P = 0.047). The logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate variables independently associated with ACLF. The following covariates were included: Gender, ascites, leukocyte count, sodium, C-reactive protein (CRP), and calprotectin. Other covariates with statistical significance in the bivariate analysis, such as hepatic encephalopathy, creatinine, INR, Child-Pugh, and MELD, were not incorporated in this analysis because they are closely related to the CLIF-SOFA score and ACLF definition. In the logistic regression analysis, ACLF was independently related to male gender (odds ratio [OR] = 2.782, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.277-6.867, P = 0.026), ascites (OR = 2.793, 95%CI: 1.270-6.143, P = 0.011), and leukocyte count (OR = 1.087, 95%CI: 1.003-1.178, P = 0.041). Serum calprotectin concentrations were not associated to the presence of ACLF in the logistic regression analysis.

Factors associated with bacterial infection were also analyzed and are depicted in Supplementary Table 3. As previously mentioned, in the bivariate analysis, higher calprotectin was observed among patients with bacterial infection detected in the first 48 h of hospitalization (581.30 vs 446.50 ng/mL, P = 0.012). A multiple logistic regression analysis was performed including the following variables: Active alcoholism, UGIB, Child-Pugh C, MELD, CRP, and calprotectin. Other variables with statistical significance in the bivariate analysis were not included in the regression analysis because they have already been included. In this analysis, infection was independently associated with high CRP values (OR = 1.027, 95%CI: 1.015-1.040, P < 0.001) and inversely related to hospitalization for UGIB (OR = 0.157, 95%CI: 0.061–0.401, P < 0.001).

Circulating calprotectin and survival in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis

During the first 30 d, 39 patients died (20%). Four patients were excluded from the survival analysis due to loss of follow-up. Survival analysis was performed considering the whole group and separately accordingly to the presence or absence of ACLF at admission. Calprotectin was not associated with 30-d survival in univariate Cox regression analysis when all patients were included (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.012, 95%CI: 0.996-1.028, P = 0.134) and when evaluating only those with ACLF at admission (HR = 0.982, 95%CI: 0.932-1.034, P = 0.491). However, when considering only subjects without ACLF, calprotectin levels were associated with 30-d mortality (HR = 1.018, 95%CI: 1.002-1.034, P = 0.024). A complete survival analysis among patients without ACLF is presented in Table 2.

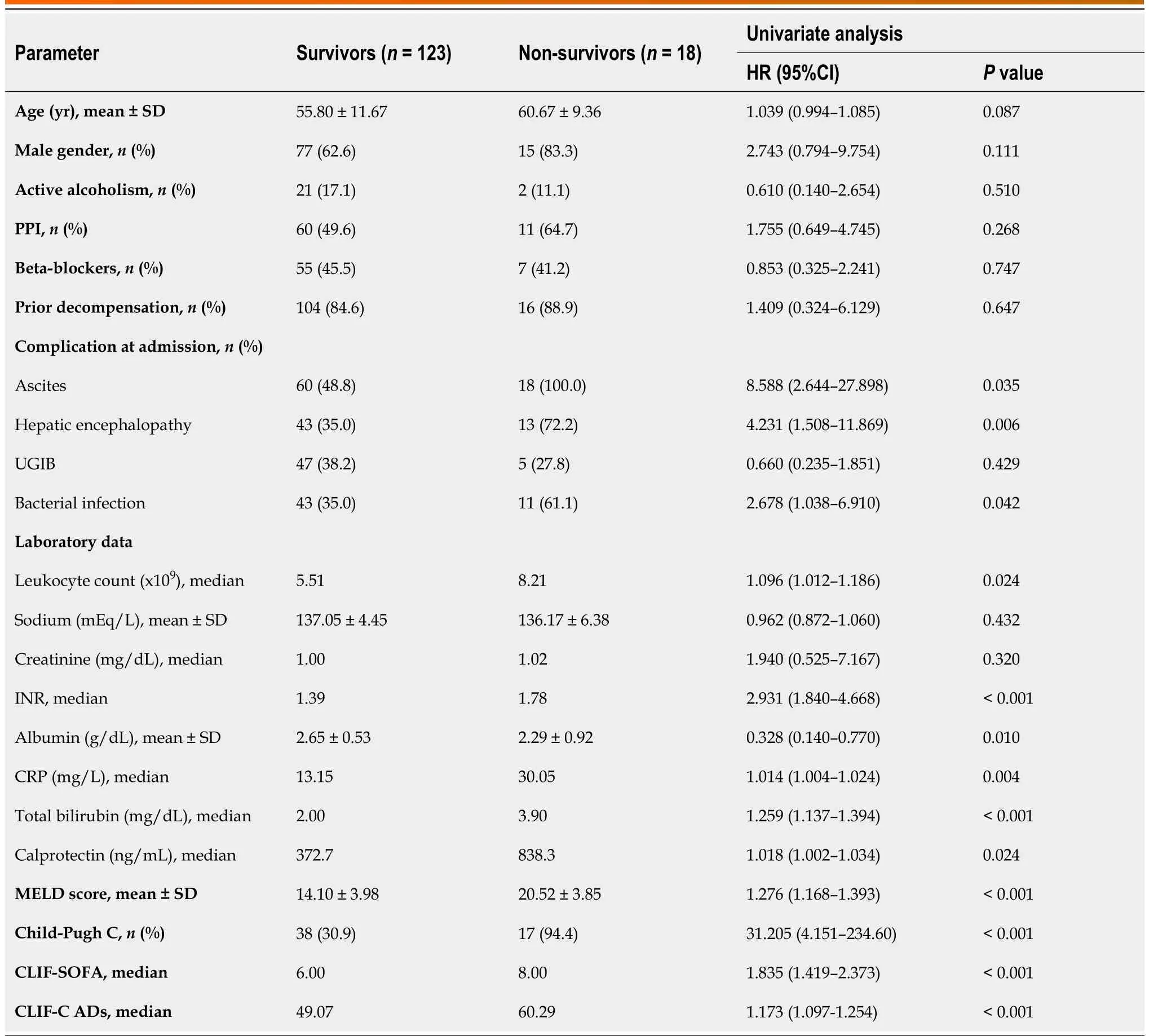

Table 2 Univariate Cox-regression analysis of factors associated with 30-d mortality among patients hospitalized for acute decompensation of cirrhosis without acute-on-chronic liver failure

Due to the relatively low number of events observed in the subgroup without ACLF, we chose to include in a multivariate Cox regression analysis only calprotectin and CLIF-C AD score, the recommended prognostic model in this context[19]. In this analysis, both serum calprotectin (HR = 1.021, 95%CI: 1.003-1.040, P = 0.023) and CLIF-C AD score (HR = 1.178, 95%CI: 1.00-1.262, P < 0.001) were independently associated with 30-d survival.

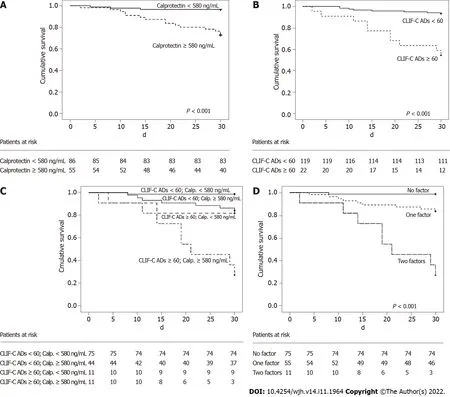

The area under the ROC curve for calprotectin to predict 30-d mortality was 0.773 ± 0.058 in patients without ACLF. Figure 3A shows the Kaplan-Meier curve for calprotectin concentrations dichotomized at a cutoff of 580 ng/mL. The Kaplan-Meier survival probability was 96.5% in patients with calprotectin levels < 580 ng/mL and 72.7% for subjects with results ≥ 580 ng/mL (P < 0.001). At this cutoff point, calprotectin levels showed a sensitivity of 83.3%, specificity of 67.5%, positive predictive value of 27.3%, and negative predictive value of 96.5% for predicting 30-d mortality. The positive likelihood ratio was 2.563 and the negative likelihood ratio was 0.247.

The Kaplan-Meier survival probability was also calculated according CLIF-C AD score categorized at a cutoff of 60[19]. The Kaplan-Meier survival probability was 93.3% in individuals with a CLIF-C AD score < 60 and 54.5% in those with a value ≥ 60 (P < 0.001) (Figure 3B). At this cut-off point, CLIF-C AD score showed a sensitivity of 55.6%, specificity of 90.2%, positive predictive value of 45.5% and negative predictive value of 93.3% to predict 30-d mortality. The positive likelihood ratio was 5.694 and the negative likelihood ratio was 0.492.

A subsequent analysis associating both variables was performed. The Kaplan-Meier survival probability was 98.7% in subjects with a CLIF-C AD score < 60 and calprotectin concentration < 580 ng/mL, 84.1% in subjects with a CLIF-C AD score ≥ 60 and calprotectin concentration < 580 ng/mL, 81.4% in subjects with a CLIF-C AD score < 60 and calprotectin concentration ≥ 580 ng/mL, and 27.3% in subjects with a CLIF-C AD score ≥ 60 and calprotectin concentration ≥ 580 ng/mL (Figure 3C).

Since the second and third groups had very similar survival rates, 84.1% and 81.4%, both were grouped. Thus, three groups were obtained according to the presence of factors CLIF-C AD score ≥ 60 or calprotectin ≥ 580 ng/mL. The Kaplan-Meier analysis showed a survival probability of 98.7% in patients without any of the factors (CLIF-C AD score < 60 and calprotectin < 580 ng/mL), 83.6% in the presence of one factor (CLIF-C AD score ≥ 60 or calprotectin ≥ 580 ng/mL), and 27.3% in the case of two factors (CLIF-C AD score ≥ 60 and calprotectin ≥ 580 ng/mL). The P value was 0.002 when the first and second groups were compared, and P < 0.001 for comparison between the first and third groups, and also for comparison between the second and third groups (Figure 3D). Based on this new classification, CLIF-C AD score ≥ 60 combined with calprotectin ≥ 580 ng/mL showed a sensitivity of 44.4%, specificity of 97.6%, positive predictive value of 72.7%, and negative predictive value of 92.6% to predict 30-d mortality. The positive likelihood ratio was 18.222 and the negative likelihood ratio was 0.569.

Figure 2 Box plot of serum calprotectin levels in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis according to the presence of specific complications. The line across the box indicates the median value; the box contains the 25% to 75% interquartile range; and the whiskers represent the highest and the lower values. A-D: Significantly higher calprotectin levels were observed among patients with (A) acute-on-chronic liver failure (P = 0.047), (B) infection (P =0.012), (C) ascites (P = 0.004), and (D) hepatic encephalopathy (HE) (P = 0.026); E: Lower levels of calprotectin were observed among patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) (P = 0.036); F: Higher levels in patients with hepatitis C virus infection (HCV) (P = 0.001).

Figure 3 Cumulative 30-d survival of patients hospitalized with acute decompensation of cirrhosis without acute-on-chronic liver failure according to calprotectin levels categorized at 580 ng/mL and CLIF-C acute decompensation score at 60. A: The Kaplan-Meier survival probability was 96.5% in subjects with a calprotectin level < 580 ng/mL and 72.7% in those with a value ≥ 580 ng/mL (P < 0.001); B: The Kaplan-Meier survival probability was 93.3% in individuals with a CLIF-C acute decompensation (AD) score < 60 and 54.5% in those with a value ≥ 60 (P < 0.001); C: The Kaplan-Meier survival probability was 98.7% in subjects with a CLIF-C AD score < 60 and calprotectin concentration < 580 ng/mL, 84.1% in subjects with a CLIF-C AD score ≥ 60 and calprotectin concentration < 580 ng/mL, 81.4% in subjects with a CLIF-C AD score < 60 and calprotectin concentration ≥ 580 ng/mL, and 27.3% in subjects with a CLIF-C AD score ≥ 60 and calprotectin concentration ≥ 580 ng/mL; D: The Kaplan-Meier survival probability was 98.7% in subjects with none of the factors (CLIF-C AD score < 60 and calprotectin concentration < 580 ng/mL), 83.6% in subjects with one of the factors (CLIF-C AD score ≥ 60 and calprotectin < 580 ng/mL or CLIF-C AD score < 60 and calprotectin ≥ 580 ng/mL), and 27.3% in subjects with both factors (CLIF-C AD score ≥ 60 and calprotectin ≥ 580 ng/mL), in which P = 0.002 between the first and second groups, and P < 0.001 between the first and third, and between the second and third groups.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, no differences in serum calprotectin levels were observed when patients with stable cirrhosis were compared with individuals hospitalized for AD. However, healthy subjects had lower calprotectin concentrations than both groups of patients with cirrhosis. Plasma calprotectin levels were previously studied in patients with alcohol-induced cirrhosis. In that study including 84 patients and 16 healthy controls, no differences in calprotectin levels were found between healthy controls and subjects with compensated or decompensated alcoholic cirrhosis[9]. Higher circulating calprotectin in patients with cirrhosis included in the present study probably reflects specific characteristics of our cohort, but also may be a consequence of the relatively small sample size of that preliminary study. Conversely, other studies have shown that faecal calprotectin concentrations are higher in patients with liver cirrhosis compared to healthy patients[20,21] and in acute decompensation when compared to stable cirrhosis[22].

Significantly higher serum calprotectin levels were observed in patients with ascites, those with hepatic encephalopathy, and Child-Pugh C patients. Data on circulating calprotectin concentrations in cirrhosis are scarce. An early study by Homann and colleagues observed no relationships between plasma calprotectin and variables related to liver disease severity, such as albumin and total bilirubin[9]. On the other hand, another paper from the same group reported a weak positive correlation between calprotectin plasma levels and the Child-Pugh score, but without significant difference between Child-Pugh classes[10]. In the present study, higher calprotectin levels were associated with the presence of ACLF and bacterial infection in the bivariate exploration, but not in the logistic regression analysis. Although no previous studies addressed this biomarker and ACLF, higher plasma calprotectin was associated with bacterial infection in patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis in a small study[9]. In addition, ascitic fluid calprotectin has been recently reported to be increased in SBP and might represent a practical alternative to the traditional ascitic polymorphonuclear cell count[23]. Outside the context of liver cirrhosis, elevated circulating calprotectin was reported in other conditions characterized by a robust inflammatory response such as tuberculosis[24], sepsis[25,26], COVID-19[27], and several rheumatic diseases[28].

When we evaluated the group of patients hospitalized for complications of cirrhosis as a whole, serum calprotectin concentrations were not associated with prognosis. On the other hand, when we addressed only those with AD without ACLF, circulating calprotectin was related to 30-d mortality even after adjustment for CLIF-C AD score. In a previous study including patients with alcoholic cirrhosis, plasma calprotectin levels was related to a shorter survival, exhibiting higher prognostic value than other classical markers in these patients, such as albumin, bilirubin, and ascites[9]. Later, the same research group studied plasma and ascitic fluid calprotectin concentrations in patients with various etiologies of liver cirrhosis[10]. In both studies, plasma calprotectin was a significant marker of poor survival in alcohol-induced cirrhosis, but had no prognostic value in other etiologies[9,10]. It is noteworthy that this finding of a possible selective regulation of calprotectin in alcoholic liver disease was not confirmed in a longitudinal study of active drinkers, in which patients and controls had similar fecal calprotectin values[29]. These studies predated the establishment of the ACLF concept and, unlike our study, did not consider the categorization of patients in AD or ACLF. Patients with cirrhosis requiring hospitalization for AD episodes are known to have a widely variable prognosis, depending on whether or not they have ACLF[18]. ACLF impacts not only the natural history of cirrhosis, but also the progression of cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction that migrates to a predominantly immunodeficient phenotype similar to that found in sepsis[30]. Thus, an influence of ACLF on circulating inflammatory markers is expected and further studies are still needed to explain the difference in the prognostic value of calprotectin in patients with AD and ACLF.

CLIF-C AD score was devised as a prognostic parameter in patients hospitalized for AD of cirrhosis without ACLF. In the original study, it was established that patients with a score ≥ 60 should be classified as having a high risk for 90-d mortality, with rates above 30%[19]. In the present study, patients were grouped into three categories according to the observed prognostic factors (CLIF-C AD score and calprotectin level). The Kaplan-Meier survival probability was 98.7% in subjects with none of the factors (CLIF-C AD score < 60 and serum calprotectin < 580 ng/mL), 83.6% in subjects with either factor (CLIF-C AD score ≥ 60 or serum calprotectin ≥ 580 ng/mL), and 27.3% in subjects with both factors (CLIF-C AD score ≥ 60 and serum calprotectin ≥ 580 ng/mL). A similar cutoff point of calprotectin (524 ng/mL) was previously suggested to assess survival in alcohol-induced cirrhosis[10]. Thus, the combination of the two factors may be useful in identifying patients with a very low 30-d mortality rate, allowing for better individualization of care and eventually establishing criteria for early hospital discharge, thus reducing complications of prolonged hospitalization[19]. On the other hand, a high-risk group (CLIF-C AD score ≥ 60 and serum calprotectin ≥ 580 ng/mL) was also identified, which have a 30-d survival (27.3%) similar to patients with grade 3 ACLF (23.3%)[18]. Those patients at the high category might be candidates for early interventions that could improve survival, including evaluation for liver transplantation.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, serum calprotectin levels are increased in patients with cirrhosis and correlated with variables associated with the severity of liver disease. Higher circulating calprotectin is associated with a worse 30-d survival in those hospitalized for AD without ACLF, but not among ACLF patients. The combination of serum calprotectin and CLIF-C AD score is able to better stratify the prognosis and may be particularly useful in clinical practice to early identify patients with AD of cirrhosis and a very low short-term survival, even in the absence of ACLF at admission.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research methods

This is a prospective cohort study that included three study groups: 200 subjects hospitalized for complications of cirrhosis, 20 outpatients with stable cirrhosis, and 20 healthy controls. Serum calprotectin was collected at hospital admission in the group with acute decompensation. Hospitalized patients were followed for 30 d for survival analysis

Research results

Higher calprotectin was associated with variables related to more advanced liver disease, acute-onchronic liver failure (ACLF), and infection. Calprotectin was not associated with survival among patients with ACLF. In patients with acute decompensation without ACLF, higher calprotectin was inversely associated with 30-d survival. The combination of calprotectin with the CLIF-C AD score offered a better prognostic discrimination than the variables alone.

Research conclusions

Serum calprotectin are increased in liver cirrhosis and correlated with variables associated with the severity of liver disease. Higher circulating calprotectin is associated with a worse 30-d survival in those hospitalized for complications of cirrhosis without ACLF. The combination of serum calprotectin and CLIF-C AD score is able to better stratify the prognosis than any of the factors alone.

Research perspectives

The routine incorporation of the calprotectin test is a reality. Serum calprotectin may allow early identification of patients with a very low short-term survival, even in the absence of ACLF at admission. Larger, multicentric future studies are recommended to validate these results.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions: Schiavon LL and Narciso-Schiavon JL designed the research; Rateke ECM and Matiollo C contributed to sample handling and general laboratory analysis; De Augustinho FC, Zocche TL, Silva TE, Macalli C, and Narciso-Schiavon JL collected the clinical data; Moura EQA Andrigueti M, Gomes LO, and Farias MR contributed to specific laboratory analysis; Schiavon LL and Matiollo C analyzed the data and wrote the paper; Farias MR and Narciso-Schiavon JL reviewed the manuscript.

Supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico.

Institutional review board statement: The study protocol complies with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee on Human Research of the Federal University of Santa Catarina.

Informed consent statement: All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: There is no conflict of interest regarding this manuscript.

Data sharing statement: Technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset available from the corresponding author upon request at leo-jf@uol.com.br. Participants gave informed consent for data sharing.

STROBE statement: The authors have read the STROBE Statement—checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement—checklist of items.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

ORCID number: Camila Matiollo 0000-0001-6144-6776; Elayne Cristina de Morais Rateke 0000-0002-0459-7903; Emerita Quintina de Andrade Moura 0000-0003-4051-5335; Michelle Andrigueti 0000-0002-1479-3780; Fernanda Cristina de Augustinho 0000-0003-3190-7177; Tamara Liana Zocche 0000-0002-7948-0953; Telma Erotides Silva 0000-0002-9041-8915;Lenyta Oliveira Gomes 0000-0001-8971-5827; Mareni Rocha Farias 0000-0002-4319-9318; Janaina Luz Narciso-Schiavon 0000-0002-6228-4120; Leonardo Lucca Schiavon 0000-0003-4340-6820.

S-Editor: Liu JH

L-Editor: Wang TQ

P-Editor: Liu JH

World Journal of Hepatology2022年11期

World Journal of Hepatology2022年11期

- World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Multiple hepatic infarctions secondary to diabetic ketoacidosis: Acase report

- Liver test abnormalities in asymptomatic and mild COVID-19 patients and their association with viral shedding time

- Current status of disparity in liver disease

- Haemochromatosis revisited

- Current management of liver diseases and the role of multidisciplinary approach