Enhanced recovery and medical management after head and neck microvascular reconstruction

Sunder Gidumal, Douglas Worrall, Noel Phan, Anthony Tanella, Samuel DeMaria, Brett Miles

1Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029, USA.

2Department of Anesthesiology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029, USA.

Abstract

Keywords: Enhanced recovery, fast track surgery, major head and neck surgery, preoperative carbohydrate loading,evidence-based medicine, surgical outcomes, length of stay, cost

INTRODUCTION

Protocols to expedite patient recovery after surgery were first pioneered in the late 1990s by colorectal and cardiothoracic surgeons looking to reduce length of hospital stay and postoperative complications.Conventional postsurgical care for these populations frequently involved a hospital stay of five to ten days and significant postoperative complications, such as prolonged ileus, loss of physical mobility, and poor wound healing[1-4]. Surprisingly, innovations in surgical technique, such as the advent of laparoscopy over open abdominal surgery, had a limited impact on patient recovery; thoughtful standardization of pre-,intra-, and post-operative care, however, was shown to improve outcomes and enhance recovery after surgery significantly. A paper by Kehletet al.[5], “Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome”, is often credited as the first systematic review to compile and evaluate many of these perioperative interventions. From this paper and others, Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) was developed and gave way to the significant developments in this field over the last decade.

The foundational concept of ERAS is that major surgery incites a significant biologic stress response in the patient. Length of stay and severity of postoperative complications correlate with the magnitude of this stress and how it is managed. Interventions aimed at reducing the magnitude of this stress response are paramount and are performed in the following ways[6-8]:

· A multidisciplinary team working together to reduce the impact of surgery;

· A multimodal approach to resolving issues that delay recovery and cause complications;

· A standardized, evidence-based approach to all phases of perioperative care;

· Changes in management using interactive and continuous audits.

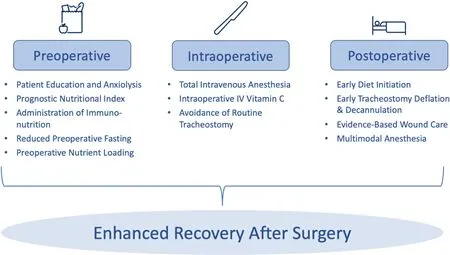

Some reviews in multiple surgical fields have been performed on this subject in efforts to compile the most compelling interventions for readers to learn from and implement in their own institutions. Our research team has published previously on this topic, specifically highlighting interventions applicable to head and neck surgery and its patient population[8]. This review builds upon and emphasizes that work while also focusing on compelling perioperative interventions that have not yet reached universal acceptance despite convincing evidence and thus have not been discussed much elsewhere. While certain well-established interventions, such as perioperative antibiotics and deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis, often have the strongest data to support their use, we have included these established practices only for completeness in the final section on “accepted practices”. We hope to focus the attention of our readership on the interventions that may not currently be in practice at their respective institutions in the hopes of future widespread investigation and implementation [Figure 1].

Figure 1. Overview of perioperative ERAS interventions. The interventions highlighted in this review have been chosen because they have demonstrated compelling evidence to merit their inclusion in an ERAS program, but they still lack universal acceptance among those providing care for patients undergoing head and neck oncologic surgery.

ERAS for major head and neck surgery

ERAS protocols have become increasingly popular in the field of head and neck surgery over the last decade[9-11]. The ERAS Society, a nonprofit medical society, was formed in 2010 to promote and develop ERAS programs and build on foundational work in enhanced recovery in colorectal and thoracic surgery from the beginning of the century. The official ERAS society recommendations for head and neck surgery were published in 2017, setting off a slew of research both to report outcomes of the implementation of these protocols as well as to trial new interventions that build off the tenets of ERAS[12].

While the composition of interventions comprising an ERAS protocol has differed amongst the many head and neck institutions reporting results of their ERAS implementation, the results of these implementations are often similar. In particular, implementation studies have demonstrated that, compared to control groups treated with conventional perioperative care, ERAS patient cohorts experience reduced ICU and hospital stays, reduced delay between surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy, diminished narcotic use in the first 24-72 h after surgery, and fewer overall complications[13-16].

Rather than focusing on the clinical outcomes of implementing a comprehensive ERAS pathway as many groups have already done successfully, we instead direct our attention to individual interventions themselves and the physiology that explains their success. These enhanced recovery interventions are chronologically organized into three categories: (1) preoperative, which includes both pre-and postadmission interventions; (2) intraoperative; and (3) postoperative, which includes both pre-and postdischarge interventions. We seek to shed light on select interventions within each category that have demonstrated clinical success and have sound physiologic explanations but have not yet been established in widespread use; we make a case for their implementation in future ERAS protocols.

Preoperative interventions

Patient education and anxiolytics

Patients undergoing major head and neck surgery often present stress and anxiety on the day of surgery.Fear of surgical and anesthetic complications, anxiety about a prolonged hospital stay, and the uncertainty surrounding a cancer treatment course are all factors that can contribute to increasing a patient’s psychological stress levels. Furthermore, previously published bio-behavioral models of stress have demonstrated that psychological stress worsens wound healing and increases the risk of tumor recurrence through the same mechanisms as physiological stress. These mechanisms include increased insulin and cortisol secretion, increased production of arachidonic acid, and increased catabolism[8,17,18].

A patient’s understanding of their planned treatment is often limited to that discussed in a preoperative clinic visit, which may parallel diagnostic discovery related to their disease process. Enhanced preoperative communication between surgeon and patient may alleviate patient anxiety and mitigate increased stress levels before surgery. It may be done by building a shared understanding of the surgical plan and setting expectations regarding the pre-and post-operative course[17-19]. Additionally, an independent discussion with the anesthesiologist in the preoperative setting has been shown to reduce stress levels[18,19]. While the value of these discussions is obvious, the time required to adequately counsel patients undergoing complex head and neck surgery is often a barrier in the real-world setting, given the pressures of clinical practice. While these discussions’ most effective timing and exact content have not been well described, managing patient expectations and improving their understanding of treatment course are recommended as an early part of enhanced recovery protocol and represents a target for improvement[8,20,21].

Assessment of preoperative nutritional status

Up to 57% of head and neck cancer patients suffer from malnutrition caused by catabolic tumor cytokines,mechanical obstruction within the aerodigestive tract, and anorexia from alterations in neurotransmitters and immunoregulatory hormones[8,22]. Malnutrition leads to an immunocompromised state and predisposes patients to postoperative complications such as poor wound healing, infection, poor survival outcomes, and increased risk of locoregional recurrence[8,23].

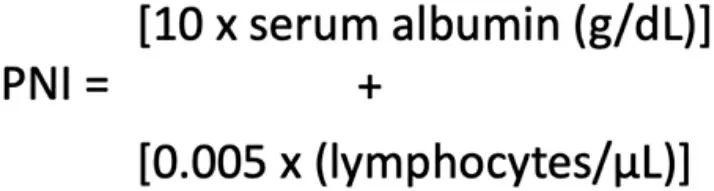

Originally developed in 1984 to screen surgical candidates for malnutrition prior to gastrointestinal surgery,Onodera’s prognostic nutritional index (PNI) has gained significant traction as a preferred nutritional screen prior to head and neck surgery[24]. PNI uses a simple formula [Figure 2] to calculate a nutritional score with just two variables: serum albumin and total lymphocyte count. A PNI ≤ 40 is associated with a significantly increased risk of postoperative complications Clavien-Dindo grade II and IIIa as well as prolonged hospital stay[25]. Furthermore, a PNI score under 40 has been shown as a stronger and more consistent prognostic indicator for postoperative complications due to malnutrition than body mass index[25]. In addition to the surgical setting use, PNI has also been used successfully to predict worse outcomes after chemotherapy, demonstrating the wide-ranging applicability of the metric as an indicator of malnutrition[26]. While other validated nutritional screens have also been employed to screen for nutritional status in head and neck populations, no single metric of malnutrition has yet been established as the standard of care[26]. Interestingly, despite the supporting evidence, many institutions do not utilize PNI routinely in clinical practice. It is believed that all patients presenting as candidates for head and neck surgery should be screened using PNI, and patients should be referred to a dietician for further evaluation and management.

Figure 2. Formula for Onodera’s Prognostic Nutritional Index (PNI).

Preoperative immunonutrition

When possible, patients who suffer from malnutrition may benefit from a brief delay prior to surgery to undergo nutritional prehabilitation, a practice that has been shown to improve postoperative outcomes. The administration of immunonutrition, nutritional formulas containing essential nutrients to promote adequate immune response after medical treatment or surgery, has demonstrated improved outcomes[27]. In addition to supplementing caloric intake to combat malnutrition, immunonutritional formulas are often comprised of a variety of immunoactive additives, including L-arginine, omega-3 fatty acids, and RNA nucleotides. L-arginine, in particular, has garnered the most attention for its beneficial impact on wound healing and infection prevention prior to surgery.

L-arginine (now “arginine”), an amino acid, is an essential component of both the urea cycle and the nitric oxide cycle[28]. Although arginine is synthesized in the kidney from citrulline, additional dietary arginine is needed for growth, wound repair, and infection prevention[29]. Arginine improves wound healing through two mechanisms: the generation of nitric oxide as well as the upregulation of growth hormone and insulinlike growth factor. Firstly, nitric oxide (NO), the chemical that forms the basis for many vasodilatory medications such as nitroglycerin, is generated from arginine in the nitric acid cycle. The biological effects of NO on vascular tone have been shown to improve blood flow to free flaps in both healthy and diseased individuals, with effects lasting for weeks after administration[30,31]. Secondly, dietary arginine administration has been shown to elevate serum levels of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1). These hormones are key components of the anabolic response required for wound healing and are associated with increased collagen production[31,32]. The improved wound healing afforded by arginine administration has been shown to reduce fistula formation after surgery for oral and laryngeal cancer, with greater effect associated with higher doses up to 20 g/day[33-35].

Arginine also improves infection prevention. Firstly, the increased blood flow due to NO generation improves microbial defenses by increasing white blood cell delivery to tissue. Secondly, through mechanisms that are not completely understood, arginine increases the response of peripheral lymphocytes to mitogenic stimulus and restores the activity of macrophages often depressed by physiologic stress[31,36].However, it is notable that adverse clinical outcomes have been reported with the administration of arginine after the establishment of a severe infection rather than as infection prophylaxis, a finding that has been attributed to the maladaptive reduction in blood pressure that can come from NO generation in the setting of septic hypotension[37].

Very recent outcomes research has further substantiated claims that arginine improves both wound healing and infection prevention. A Cochrane meta-analysis from 2018 of 19 randomized controlled trials evaluating immunonutrition administration prior to head and neck surgery demonstrated a significant reduction in the rate of fistula formation among patients who received the intervention[38]. Furthermore, two extensive studies published after this meta-analysis also demonstrated significant reductions in hospital length of stay and wound infection complications[27,39]. While the most effective dosing and timing of preoperative supplementation are not yet established, it is our view that all patients, particularly those with malnutrition, should receive immunonutritional supplementation prior to scheduled head and neck surgery to reduce the risk of wound complications and prolonged hospital stay.

Reduced fasting

For decades, patients have been instructed not to eat or drink after midnight the day before surgery in order to mitigate the risks of aspiration during anesthetic induction and intubation. Nothing by mouth, or “nil per os (NPO)”, after midnight is thought to cause dehydration, increase anxiety and physiologic stress, and induce a catabolic state that increases insulin resistance and perioperative hyperglycemia[40]. Perioperative hyperglycemia is associated with numerous perioperative complications such as the increased risk of infection, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation, and interventions that reduce hyperglycemia have successfully reduced postoperative complications[41,42]. Furthermore, the instructions of nothing by mouth after midnight might be misconstrued as instructions not to take certain daily medications, such as antihypertensives, the abstinence from which can increase cardiac lability in the perioperative period[41-43].

The American Society for Anesthesiologists (ASA) most recently published new preoperative fasting guidelines in 2017, which are liberal than the conventional teaching of NPO after midnight and consider the risks of complications imparted by more stringent fasting criteria[44]. These updated guidelines allow for the consumption of heavy foods up to 8 h before surgery, light foods up to 6 h before surgery, and clear liquids up to 2 h before surgery. They assume normal gastrointestinal anatomy and function and apply to elective procedures requiring general anesthesia, regional anesthesia, or sedation. Because many patients undergoing major head and neck surgery have disease processes or comorbidities that may increase the risk of aspiration (e.g., gastroesophageal reflux disease, altered anatomy along the upper aerodigestive tract),many institutions use the cutoff of 8 h of fasting for any solid foods, light or heavy.

Perioperative nutrient loading (glucose, protein)

The physiologic stress of surgery induces a metabolic response that results in insulin resistance and subsequent hyperglycemia[40,45]. As previously mentioned, hyperglycemia in the intraoperative and postoperative settings is associated with significant morbidities, such as poor wound healing, atrial fibrillation, pulmonary complications, and heart failure[41,42]. Preoperative oral carbohydrate loading,through consumption of a carbohydrate-rich clear liquid up to 2 h before surgery, has been shown to increase insulin sensitization in the intraoperative setting[46]. This practice minimizes preoperative gluconeogenesis and glycogen depletion and reduces insulin resistance by 50%, lowering the risk of perioperative hyperglycemia and its associated comorbidities[46,47]. Evidence indicates that many patients are likely to benefit from the practice of oral carbohydrate loading with carbohydrate-rich clear liquids up to 2 h before surgery.

While solid data on the benefits of preoperative carbohydrate loading has been recognized, newer evidence suggests that patients who add protein to their preoperative carbohydrate bolus demonstrate even fewer postoperative complications than those who take carbohydrates alone[48]. While the mechanism of action is not yet clear, it is thought that in addition to further reducing insulin resistance, the addition of protein or amino acids to the preoperative oral carbohydrate load reduces the acute-phase inflammatory response to surgery. It has been demonstrated through measurements of c-reactive protein, a marker of inflammation,which appears to be lower in patients taking protein with their preoperative carbohydrate than those taking carbohydrates alone and those taking just water before surgery[48-50]. Prior studies have demonstrated that elevated levels of inflammatory markers in the first 24 h after surgery are associated with higher rates of postoperative complications; thus, through this mechanism, protein supplementation prior to surgery is thought to reduce postoperative complications[51]. Although a further study will be required to elucidate the precise mechanism of action of this intervention, we recommend considering preoperative oral loading with 25 g of carbohydrates and 7 g of protein or amino acids to reduce insulin resistance and inflammation perioperatively.

Intraoperative interventions

Anesthetic agents

Short-acting anesthetic agents, such as propofol and remifentanil, are preferred for maintaining anesthesia during head and neck surgery. Long-acting agents are associated with an increased risk of residual neuromuscular blockade and critical respiratory events, leading to worse patient outcomes[52,53].Furthermore, recent data suggest an association between volatile anesthetics, such as desflurane,sevoflurane, isoflurane, and increased rates of cancer metastasis. The completion of an ongoing randomized controlled trial, General Anesthetics in Cancer Resection Surgery (GA-CARES Trial - NCT03034096), may shed more light on whether the choice of general anesthetic impacts long-term cancer morbidity and mortality. While those data are completed, we currently favor the use of short-acting total intravenous anesthesia in place of traditional inhaled anesthetic agents.

Vitamin C administration

Recent data support the administration of intravenous vitamin C in the perioperative setting as a mechanism to reduce postoperative pain and narcotic usage[54,55]. Vitamin C, a water-soluble vitamin found widely in fruits and vegetables, plays a prominent role in wound healing and hemostasis. It is best exemplified by the pathologic state that develops in vitamin C deficiency, scurvy, which is characterized by spontaneous bleeding, anemia, and gingival ulceration. Vitamin C is also known that have antinociceptive properties that exert an ameliorative effect on chronic pain syndromes[56-58]. Vitamin C, administered intravenously shortly before surgery or shortly after anesthetic induction, appears to significantly reduce pain scores and opioid use starting 1 h after surgery and lasting up to 48 h[54]. Given the remarkably low acute toxicity of vitamin C and the absence of any reported adverse effects of this practice, practitioners may wish to consider intravenous administration of 3 g of vitamin C 30 min after anesthetic induction.

Avoiding routine tracheostomy

Routine tracheostomy is often used to secure the airway following reconstructive head and neck surgery within the oral cavity. This practice reduces airway resistance, improves patient comfort, and reduces the need to manipulate the newly reconstructed field in cases in which postoperative ventilatory support is required[59]. The practice of routine tracheostomy in head and neck surgery may also be rooted in anecdotal surgical experience or anesthesiologist’s comfort levels. However, tracheostomy is associated with a high complication rate of 8%-45%[60]. These complications include tracheomalacia, tracheal stenosis, obstruction of the tracheostomy cannula, tracheo-innominate and tracheoesophageal fistulas, pneumonia, and bleeding to adjacent structures[61]. Furthermore, the presence of a tracheostomy tube increases rates of dysphagia and aspiration because the laryngeal elevation is restricted during swallowing[59].

As an alternative to routine tracheostomy, recent evidence supports overnight orotracheal or nasotracheal intubation as a means to secure the airway against the risk of postoperative airway edema. In some cases,extubation in the operating room with close observation is the most appropriate management. Compared with patients who underwent tracheostomy, patients who were managed with overnight intubation were found to have reduced overall length of hospital stay, the incidence of postoperative dysphagia, time to first oral intake, and rates of lower respiratory infections[59,62,63]. The downsides of overnight intubation include prolonged sedation, reliance on an intensive care setting to provide management for intubated patients requiring a ventilator, and the lack of a secure airway once extubation is performed. Interestingly, the outcomes classically associated with prolonged sedation such as atelectasis and increased length of stay,however, have been shown to occur more frequently in patients with tracheostomies[62]. Furthermore, the increased cost associated with an ICU stay is more than offset by the reduction in cost associated with an earlier time to discharge[64,65]. However, certain procedures may preclude the possibility of avoiding a tracheostomy due to a less stable airway or aerodigestive reconstruction. While we recognized the challenges of airway management and certainly favor a case-by-case approach, we recommend that routine tracheostomy practices should be avoided.

Postoperative interventions

Early diet initiation

Early initiation of oral diet is an essential tenet amongst ERAS programs in all surgical fields[66-68]. It has been established that early postoperative enteral, rather than parenteral, feeding reduces the risk of infection,improves insulin resistance, improves nutritional uptake, and ultimately reduces the length of hospital stay in surgical patients[60,69]. The increase in gastrointestinal (GI) hormone secretion associated with enteral feeding has been shown to improve both macrophagic activity and absorptive function in the GI tract and is the mechanism by which the clinical benefits of enteral feeding are attributed[70].

Head and neck patients represent a unique population due to violation of oral cavity and pharyngeal structures and have traditionally been kept nothing-by-mouth after major head and neck surgery for six to twelve days to avoid salivary fistula[71]. Postoperative enteral nutrition, either through a nasogastric or gastrostomy tube, is now common, with parenteral nutrition reserved only for patients with an absence of intestinal function or with contraindications to enteral access[12]. In the last decade, however, new evidence in the general surgery field has shown benefits of early oral feeding compared to enteral therapy. These benefits include a decreased length of stay and improved quality of life[72,73]. Furthermore, weak evidence supports early oral intake as a mechanism to preserve muscle memory associated with swallowing[74].Historically, however, head and neck services have hesitated to start an oral diet on the first postoperative day (POD-1) out of concern that overuse of the tongue and pharynx could increase the risk of wound dehiscence and fistula formation in the aerodigestive tract. Until recently, head and neck surgery data on the benefits of early oral regimens had been sparse and inconclusive[60,71]. It has led to the continued avoidance of standardized oral diet initiation for head and neck patients[8].

However, recent work in the field of head and neck surgery has demonstrated convincing evidence that initiation of oral diet on POD-1 reduces the length of stay without an increase in perioperative complications[75]. More compelling evidence now supports older studies that had occasionally shown that rates of fistula formation were not increased by early oral feeding[76-79]. Together with the aforementioned promising data seen in the general surgery populations, these findings suggest that oral feeding as early as postoperative day one is likely to improve dysphagia outcomes, quality of life, and length of stay in patients after head and neck oncologic surgery. We are currently exploring clinical trials in order to compare outcomes of early oral feedingvs.traditional approaches.

Tracheostomy management

For patients who require tracheostomy, early tracheostomy tube cuff deflation, 24 h capping trials to judge readiness for decannulation, and subsequent early decannulation are all practices that have improved outcomes in tracheostomized patients[8,12]. Additionally, recent data have supported the implementation of two new strategies for managing tracheostomies in the postoperative setting: immediate use of an uncuffed tracheostomy tube and the use of high flow oxygen therapy (HFOT).

Immediate placement of an uncuffed tracheostomy tube, rather than placement of a cuffed tube with subsequent deflation, has recently been shown to reduce time to decannulation as well as the length of stay[80]. Uncuffed tracheostomy tubes both reduce resistance to airflow around the tube, allowing for earlier assessment of readiness for decannulation, and reducing pressure on the esophagus, diminishing the risk of dysphagia in the postoperative setting. While it has been proposed that the lack of a cuff to prevent tracheal secretions from entering the lower airway may lead to increased rates of lower respiratory infection,equivalent rates of respiratory complications have been found in cuffed and uncuffed populations[80].

High flow oxygen therapy through a tracheostomy tube has reduced rates of postoperative pulmonary complications in preliminary work[81]. Oxygen provided at a rate of 60 L/min from the cessation of mechanical ventilation to decannulation reduces anatomical dead space and improves airway humidification, thus decreasing the risk of mucous plugging and retention of respiratory secretions[82,83].Patients undergoing HFOT did not suffer from adverse events often associated with positive-pressure oxygenation such as pneumothorax. Furthermore, these patients benefited from reduced time to mobilization, reduced physiotherapy needs and decreased overall length of stay[81]. Further work in larger study populations will be required to establish HFOT as common practice in patients after tracheotomy.

Wound care

While postoperative wound care after head and neck surgery must be individualized, the use of specific dressing types for skin grafts and specific drainage mechanisms after neck dissection facilitate faster recovery, reduced pain, and lower infection rates. The management of the donor sites for split-thickness skin grafts (STSG) has garnered attention because patients often report more pain from the skin graft donor site than from the reconstructive sites where the majority of surgery is performed[84]. STSG donor sites heal more quickly, with fewer infections, and with less pain with hydrocolloid dressings [e.g., DuoDERM hydrocolloid (ConvaTec, Princeton, NJ)] compared with non-moist dressings (e.g., sterile gauze). While other moist dressings [e.g., Tegaderm transparent film (3M Health Care, St. Paul, MN)] lead to slower healing than hydrocolloid, they also demonstrate superiority over non-moist dressings with respect to healing and infection rates[85,86].

The use of prophylactic mechanical drains following neck dissection helps prevent the accumulation of serosanguinous fluid under skin flaps before hematomas or seromas can develop. Active drains, such as the Jackson-Pratt (JP), provide low or high levels of negative pressure to remove fluid actively from a cavity.Compared to passive drains, such as Penrose, active drains facilitate more rapid healing and better adherence to skin flaps. The often-cited concern that the negative pressure of an active drain compromises a microvascular anastomosis has not consistently been demonstrated[87].

Finally, the use of wound vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) therapy is a safe, established practice in head and neck surgery that is used to aid in the healing of complex wounds. When administered over skin graft recipient sites, wound VAC therapy has been shown to increase graft acceptance rates and decrease healing time compared to conventional wound care[88]. More recently, the immediate use of perioperative wound VAC therapy in the neck has been shown to be safe after neck dissection and microvascular anastomosis.This practice demonstrated lower rates of infection when compared to conventional therapy and was not associated with any events of vascular compromise[89]. Additional work is required to determine whether wound VAC therapy to the neck also demonstrates superiority over more conventional active draining mechanisms when applied immediately after neck dissection and microsurgery.

Pain management

The use of multimodal analgesia in the postoperative setting has been shown to reduce overall opioid use and expedite recovery[12,90-92]. Pain regimens consisting of multiple opioid-sparing analgesics, such as gabapentin, acetaminophen, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), have demonstrated synergistic effects and enable the reservation of opioids for breakthrough pain alone[13]. Gabapentin, in particular, appears to provide a significant ameliorative effect on postoperative pain and analgesic consumption when administered preoperatively and continued in the postoperative setting[93,94]. Regional anesthesia through nerve blocks performed pre- and intra-operatively has demonstrated success in reducing postoperative pain scores without a significant increase in morbidity[95,96]. Notably, however, intraoperative infusion of long-acting local anesthetics into donor sites after harvest for free flap reconstruction does not appear to reduce postoperative pain scores[97]. Additionally, the use of longer-acting opioids or those with reduced habit-forming potentials, such as methadone or tramadol, decreases overall opioid usage, reduces postoperative pain, and increases patients’ quality of life[95,98,99].

Despite widespread beliefs to the contrary, NSAIDs, such as ketorolac, celecoxib, and diclofenac, have been shown not to increase the risk of postoperative bleeding in surgical patients[100-103]. However, a synergistic effect between ketorolac and heparin used for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis appears to increase the risk of bleeding in head and neck patients when used together, despite neither agent increasing the risk when used alone[104-106]. These findings have been interpreted to caution the concomitant use of NSAIDs and heparin derivatives and to encourage individualization of the use of NSAIDs based on the analgesic needs and bleeding risk of the patient[8].

Accepted postoperative practices

Several perioperative interventions that have established as part of routine care in the setting of head and neck surgery; we mention them here for completeness. Preoperatively, the benefits of cessation of alcohol intake and smoking are widely documented; patients should be counseled to undergo these lifestyle modifications prior to surgery and encouraged to maintain these changes even after the perioperative period. Antibiotic prophylaxis against surgical site infections during clean-contaminated surgical cases is well-established, with the administration of antibiotics typically 1 h prior to surgery and continued for 24 h[107-110]. Intraoperatively, the benefits of regional nerve blocks, normothermia, prophylaxis for postoperative nausea and vomiting, and goal-directed hemodynamic therapy are published widely.Postoperatively, prophylaxis against deep vein thrombosis is a widely accepted practice to reduce the rate of postoperative venous thromboembolism[111]. Although no randomized clinical trial has been conducted to lend evidence to the utility of perioperative free flap monitoring, the practice of intensive monitoring every 1-4 h for up to 72 h after surgery has become routine[12,112-114]. Lastly, the need for and benefit of early mobilization and pulmonary physical therapy after the surgery is commonly accepted to reduce the incidence of postoperative vascular, musculoskeletal, and pulmonary complications[4,12,60,66-68,115-118].

CONCLUSION

The application of ERAS protocols to head and neck surgical populations has become more widespread in the last decade. Continued evaluation of newly developed interventions presents an ongoing opportunity to reduce the length of hospital stay, treatment costs, and complication rates and improve patient quality of life. These interventions also provide an opportunity for future investigations to improve outcomes in head and neck microvascular surgery.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to the conception of the study, performed literature analysis, and interpretation, and contributed to the manuscript writing process: Gidumal S, Worrall D, Tanella A, Phan N

Made substantial contributions to the conception of the study, contributed to the manuscript writing process, and provided administrative, technical, and material support: DeMaria S, Miles B

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All figures are original. The authors give consent for publication.

Copyright

? The Author(s) 2021.

Plastic and Aesthetic Research2021年7期

Plastic and Aesthetic Research2021年7期

- Plastic and Aesthetic Research的其它文章

- AUTHOR INSTRUCTIONS

- Lateral abdominal wall reconstruction

- Using injectabIe fiIIers for midface rejuvenation

- Advances in tracheal reconstruction and tissue engineering

- Immediate microvascular maxillofacial reconstruction and dental rehabilitation: protocol,case report, and literature review

- Overview of magnetic resonance lymphography for imaging lymphoedema