A retrospective evaluation of the quality of malaria case management at twelve health facilities in four districts in Zambia

Pascalina Chanda-Kapata, Emmanuel Chanda, Freddie Masaninga, Annette Habluetzel, Felix Masiye, Ibrahima Soce Fall

1Ministry of Health, Headquarters, Ndeke House. P.O. Box 30205,Lusaka, Zambia

2Ministry of Health, National Malaria Control Centre, P.O. Box 32509, Lusaka, Zambia

3World Health Organisation, WHO Country Office, Lusaka, Zambia

4University of Camerino, School of Pharmacy, Italy

5University of Zambia, Main Campus, Lusaka, Zambia

6World Health Organization, AFRO, Congo

A retrospective evaluation of the quality of malaria case management at twelve health facilities in four districts in Zambia

Pascalina Chanda-Kapata1*, Emmanuel Chanda2, Freddie Masaninga3, Annette Habluetzel4, Felix Masiye5, Ibrahima Soce Fall6

1Ministry of Health, Headquarters, Ndeke House. P.O. Box 30205,Lusaka, Zambia

2Ministry of Health, National Malaria Control Centre, P.O. Box 32509, Lusaka, Zambia

3World Health Organisation, WHO Country Office, Lusaka, Zambia

4University of Camerino, School of Pharmacy, Italy

5University of Zambia, Main Campus, Lusaka, Zambia

6World Health Organization, AFRO, Congo

PEER REVIEW

Peer reviewer

Davidson H. Hamer, MD, Professor of International Health and Medicine, Boston University Schools of Public Health and Medicine, Boston, MA, USA.

Tel. +260-973543773

Fax +1-617-414-1261

E-mail: dhamer@bu.edu

Comments

This is a relatively small, retrospective study of malaria case management practices in Zambia. It highlights several aspects that require attention including the use of diagnostics for all patients, decreasing the use of SP for malaria test confirmed cases, eliminating the use of anti-malarial drugs for patients WHO test negative for malaria, and assuring that all patients with confirmed malaria receive treatment.

Details on Page 503

Objective:To establish the appropriateness of malaria case management at health facility level in four districts in Zambia.

Malaria, Quality, Diagnosis, Treatment, Antimalarials, Microscopy, Rapid diagnostic tests, Zambia

1. Introduction

Prompt and effective case management is part of an essential package of integrated malaria control[1]. Malaria case management strategy involves two main components: accurate case identification with parasitological diagnosis and appropriate treatment with the recommended drugs. This is promoted through the provision of guidelines to inform WHO member states on their national malaria diagnosis and treatment guidelines[1,2].

In Zambia, malaria services are provided free of charge in line with the health reforms of 1993[3] as part of the Basic Health Care Package (BHCP) and the user fee removal policy of 2006[4]. The malaria prevention and control services are provided within this financing policy framework. The current malaria diagnosis and treatment guidelines in Zambia demand that: All patients with suspected malaria should undergo a routine confirmatory diagnostic test regardless of age, using microscopy or rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs); all uncomplicated malaria cases should be treated with the sixdose regimen of artemether-lumefantrine (AL); severe malaria cases should be treated with quinine and all these malaria services should be provided at no cost to the user[5,6].

The efficacy and cost effectiveness of the AL and sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) have been well documented by studies conducted in the country and AL has been found to be more efficacious and cost-effective than SP[7,8]. Studies on the effectiveness of the available strategies for malaria diagnosis at the point of care in Zambia have shown that RDTs are more cost-effective than microscopy and clinical diagnosis of malaria[9,10]. The availability and use of malaria interventions are monitored through the routine health management system and specialised population surveys such as the Zambia Demographic and Health Survey[11] and the Malaria Indicator Surveys[10,12,13]. All these sources of information have demonstrated that progress has been made in improving access to preventive and curative tools and corroborate findings in the World Malaria Report of 2010[2]. The impact of the malaria control interventions has been demonstrated by reductions in both parasite and anaemia prevalence[12-14] and is thought to have contributed to reductions in child mortality in Zambia[11].

However, WHO reports have recently indicated that Zambia is among the countries experiencing an increase in malaria transmission after the initial decline in disease morbidity and mortality[2]. This is supported by up to 15% increase in the in-patient malaria cases between 2008 and 2009[2,15].

Uncomplicated malaria, if treated early and appropriately does not progress to the severe form of malaria and consequently does not lead to death[1]. For malaria fatalities to be prevented, the health workers must be able to diagnose the disease definitively using RDTs or microscopy and treat with the appropriate antimalarial in line with the national diagnosis and treatment guidelines for malaria in the country[5,6].

However, little attention is paid to how the quality of these services can be enhanced. Quality and not just the availability of health services is important if health outcomes are to be improved significantly[16]. It is important to invest in quality improvements in public health facilities because more than 80% of the malaria patients in Zambia seek care from these facilities[17,18]. Thus, this paper endeavours to establish the appropriateness of malaria case management at the health facility level among four districts in Zambia.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and study sites

A retrospective evaluation of the quality of malaria case management was conducted at 12 health facilities as a part of a larger study on willingness to pay for malaria risk reduction[19]. The study sites were four districts in four of the nine provinces of Zambia. The districts were Chongwe, Chingola, Kabwe and Monze and were conveniently sampled due to the availability of secondary data which was a basis for the retrospective review. The sites represent both the high and low malaria epidemiological zones and cover both urban and rural settings[20].

2.2. Sampling

All the patient registers were reviewed for 2008 at each of the 12 level one health facilities (3 facilities per district). The year 2008 was used for the review because this is when the supply of malaria commodities (including RDTs and antimalarials) was optimal and the health facility staff had received the required in-service training on malaria case management as documented in the malaria programme reports[21,22].

2.3. Data collection

The quality assessment was based on the malaria diagnosis and treatment guidelines for Zambia which were in use in 2008. The quality of management of malaria was established for each facility, health worker characteristics were assessed and all data were entered in the transcribing sheet developed for the survey. Each health worker was identified using their hand writing. The number of health workers at each of the health facilities was limited and it was possible to identify the handwriting according to each health worker, verified by the health centre in-charge and the corresponding days of being on duty for a particular healthworker. After that, the characteristics of the health worker were verified and entered into the questionnaire. These included sex, age, profession, in service training on malaria, IMCI training, residence (rural or urban) and years of service. A total of 39 health workers were considered for analysis out of the expected 36 (3 per district). The parameters considered for quality of malaria case management were:

● Proportion of suspected malaria cases in whom a parasitemia confirmatory test (RDT or microscopy) was performed.

●Proportion of malaria parasite positive cases treated with the recommended antimalarial.

● Proportion of parasite negative cases in whom no antimalarial was prescribed.

The Pearson chi-square test was used to identify characteristics which affected quality of case management based on the differences in proportions; aP-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. The variables used were sex, profession, in service training on malaria, IMCI training, residence (rural or urban), district and years of service at the facility.

The main outcome measure was the proportion of malaria patients managed according to the national guidelines. The explanatory factors were the health worker characteristics, which were found to be associated with the malaria case management quality parameters.

The main limitation of the study is that it was a retrospective review of health facility records, therefore, the investigators could not control the record completeness for each patient’s socio-demographic variables. The missing socio-demographic variables in health facility registers was a common practice as the heath centre staff focused more on writing down the patient name, the clinical investigations and drugs prescribed rather than the age and gender of the patients. Secondly, in this study, we could not directly measure the availability of RDTs and drugs on each day but the information used for malaria commodity availability was based on program reports and the population based Malaria Indicator Survey of 2008 for Zambia.

2.4 Ethics clearance

The ethics clearance for this study was provided by the Tropical Diseases Research Centre Research Ethics Committee in Ndola, Zambia.

3. Results

3.1. Patterns of case malaria management

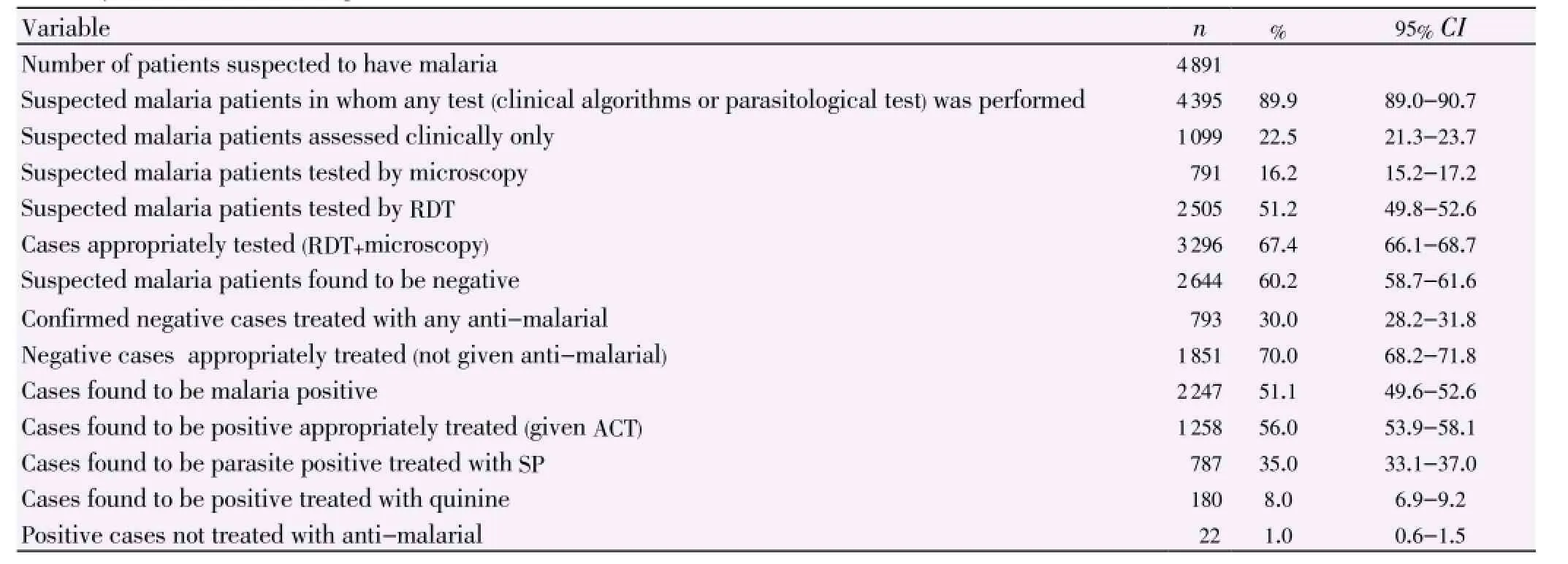

Out of all the 4 891 suspected malaria patients WHO visited the 12 health facilities between January and December 2008, more than 80% of the patients had a temperature taken to establish their fever status. About 67% (CI9566.1-68.7) of the suspected malaria patients had a confirmatory parasitological test, with more tested by RDT than by microscopy (Table 1). A fifth of the suspected malaria cases were subjected to clinical diagnosis only.

Of the 2 247 malaria cases reported by health workers (complicated and uncomplicated), 56% (CI9553.9-58.1) were treated with AL, 35% (CI9533.1-37.0) treated with SP, 8% (CI956.9-9.2) were given quinine and 1% were not given any antimalarial (Table 1). Of the reported malaria cases 29% were clinically diagnosed, 71% were parasitologically confirmed (59% by RDT and 12% by microscopy). Approximately 30% of the patients WHO were reported not to have malaria were still prescribed with an anti-malarial, contrary to the guidelines.

3.2 District variations

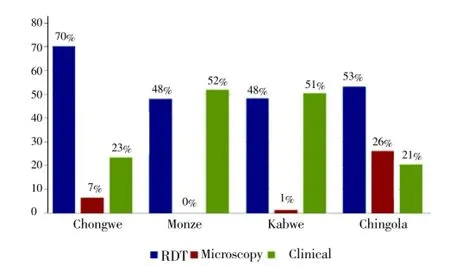

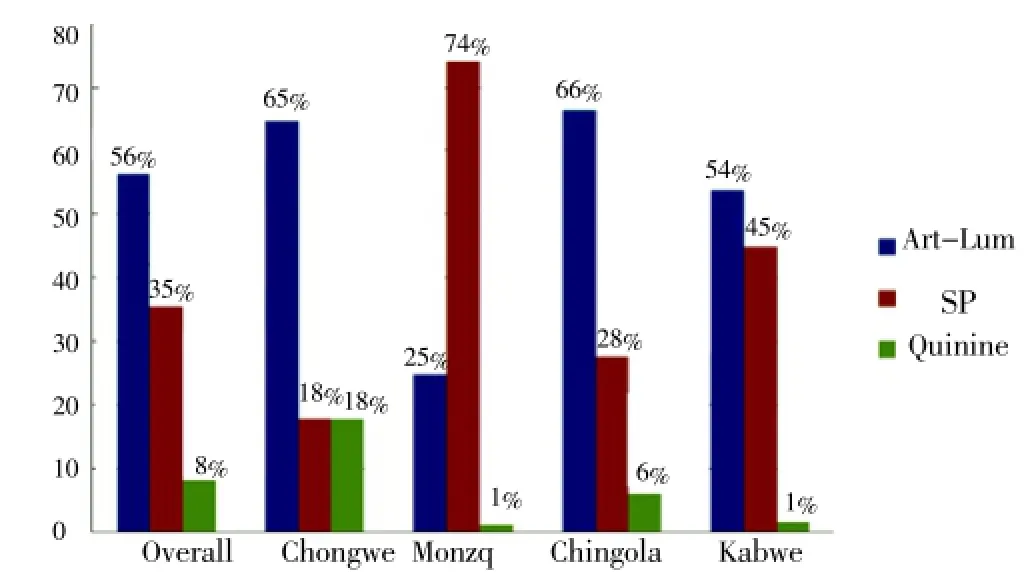

There were variations among districts in the proportion ofpatients in whom a diagnostic tool was used. In Monze and Kabwe districts, more than half of the patients were only clinically diagnosed to have malaria, whereas in Chongwe and Chingola, more than three quarters of the patients had a confirmatory test performed (Figure 1). According to NMCP programme reports, all the districts received adequate supplies of RDTs and antimalarials in 2008. Similarly, the choice of antimalarials for the treatment of cases classified to have malaria differed by district (Figure 2). Chingola and Chongwe districts showed higher prescriptions of AL, while Monze district showed the least.

Table 1 Summary of malaria case management.

Figure 1.Proprotion of patients per district in whom a diagnostic tool was used or clinical diagnosis was applied only.

Figure 2.Choice of the anti-malarials to treat malaria cases according to district.

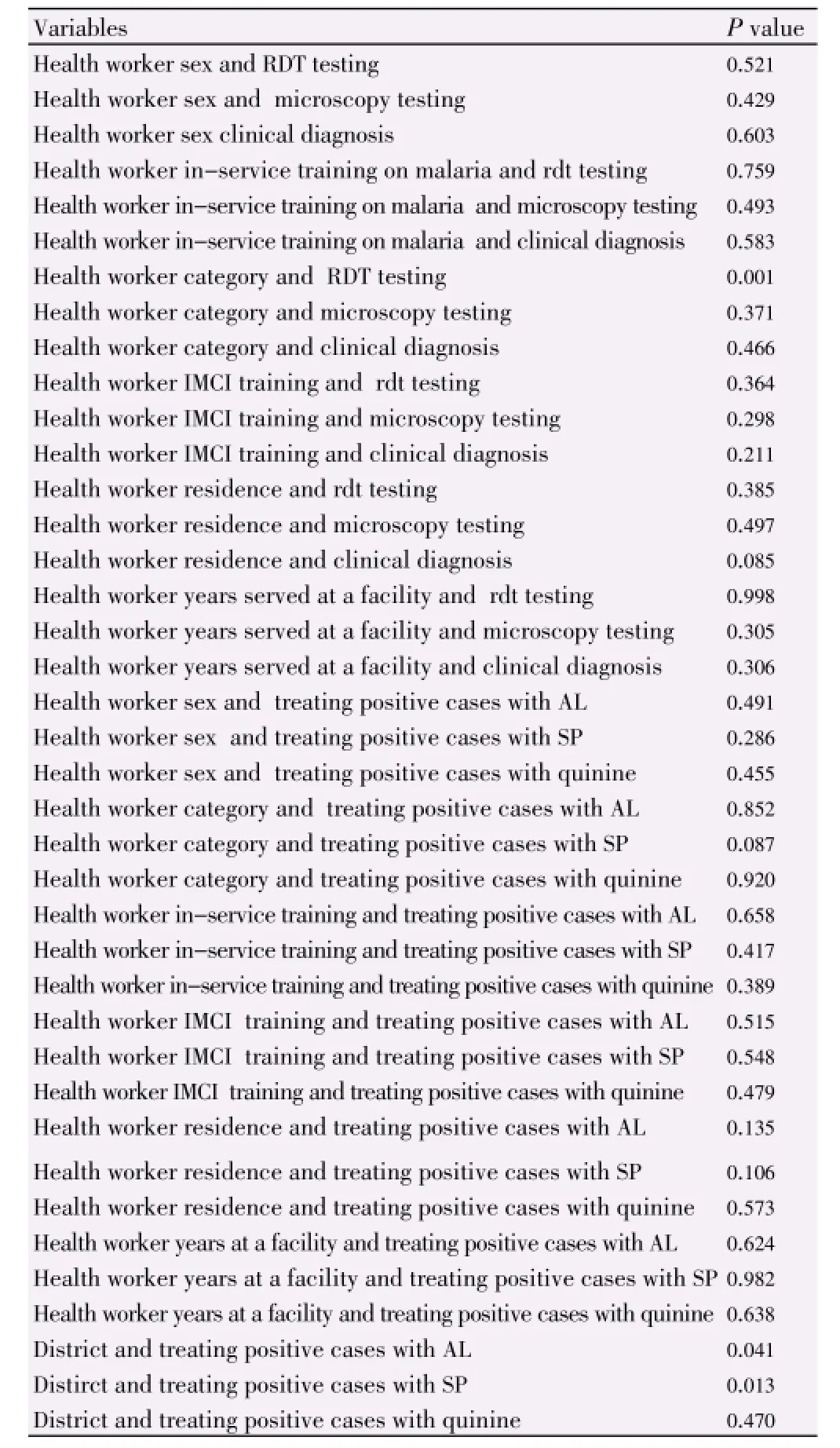

3.3 Association between health worker characteristics and quality of case malaria management

The decision whether to use the RDT test or not varied with the health worker category (P=0.001) as shown in Table 2. Nurses used RDTs two times more frequently than clinical officers and environmental health technicians. The district of residence was found to be associated with a decision to prescribe SP (P=0.001) or AL (P=0.041) respectively. Health workers from Chingola and Chongwe prescribed AL to 65% and 66% of the malaria positive cases, respectively (Figure 2) while Kabwe and Monze health workers prescribed AL to 54% and 25% malaria positive cases respectively. Health workers from Monze district prescribed SP more than AL to the malaria positive cases (74% versus 25%). Gender, in service training on malaria, years of residence in the district and length of service at the facility were not associated with diagnostic and treatment choices.

Table 2 Association between health worker characteristics and quality of case management.

4. Discussion

Malaria case management in the surveyed districts was characterised by poor adherence to diagnostic and treatment guidelines. The non-adherence was mainly in terms of: inconsistent use of confirmatory tests (RDT or microscopy) for malaria cases; prescribing anti-malarials which are not recommended (SP) in the national guidelines and prescribing anti-malarials to cases testing negative. The indicators for assessment of quality used in this study are consistent with what is internationally accepted as quality of care indicators based on a Delphi survey of national and international experts[23].

In this study, the majority of the confirmed malaria cases were confirmed by the RDT strategy and less by microscopy. These findings are consistent with earlier reports on the same in the country[22]. This is partly because the RDTs are more available in Zambia than functional microscopes[24,25]. Furthermore, RDTs are easier to scale up while microscopy scale up is a challenge due to the capital investments required[26]. It can therefore be said that the use of RDTs has played a major role in increasing the malaria case confirmation capacity in Zambia. When RDTs were absent, malaria confirmation was less than 20%[21]. Based on the findings of this study and also in line with the WHO recommendations, countries wishing to improve malaria confirmation capacity should consider investing in RDTs at all levels of care where microscopy services are not available. This has the potential to improve patient management outcomes and reduce inappropriate prescription of antimalarials[8,27,28]. A decrease in inappropriate prescription of antimalarials contributes to reducing drug pressure and consequently may help delay the emergence of parasite resistance to ACTs which are being used as first line treatment for uncomplicated malaria[29,30].

Apart from improving health outcomes, parasitological malaria confirmation has an important role in disease epidemiology because it improves the estimation of the malaria burden and better planning of the control interventions. Given that 29% of the reported malaria cases were diagnosed clinically only, it is not possible to estimate the true prevalence of malaria using the reported figures.

The diagnosis result is supposed to inform clinicians on the decision of whether to prescribe an anti-malarial or not. However, this was frequently not the case as seen by prescriptions of other anti-malarials than AL. The 35% persons prescribed SP should be considered inappropriate because this is not line with the national diagnosis and treatment guidelines. Only children less than 1 year are supposed to be prescribed SP for uncomplicated malaria. It is highly unlikely that these accounted for the 35% of the anti-malarial prescriptions because the children under 1 year account for approximately 4% of the general population[31]and malaria is less frequent in children under one year.

Among the patients with a negative parasitological test result, appropriate management implies not prescribing any anti-malarial. It was found that some patients with a negative test were still prescribed anti-malarials. This finding is similar to previous ones reported in Zambia by Hameret alin 2007[24] and elsewhere in Africa[27,32-34]. When the health workers don’t have the capacity to identify the other causes of fever they are likely to give an anti-malarial. Therefore, it is important to work with other programs for joint capacity building including supervision in order to improve the integrated management of illnesses.

This study has demonstrated that malaria in-service trainings were not associated with better malaria case management practices. This finding is similar to what has been reported in Kenya where it was found that in service training and possession of guidelines did not have an effect on the quality of malaria case management[35]. Also, in a health facility survey involving children in Malawi, it was found that in service training on malaria management was not associated with treatment quality[36]. In light of this, it is cardinal that joint program supervision should be promoted for continuous assessment of health workers’ performance.

It is important to note here that in this study, the approach was to analyse the health worker practices as opposed to asking health workers directly why they don’t prescribe AL[37] so as to avoid the ‘blame game’. In studies where health workers have been asked to account for their lack of adherence to malaria diagnosis and treatment guidelines, they have cited requiring more training or fear of stock-outs of commodities and the associated cost of ACTs[37,38]. However the latter two arguments may not always hold because the non-prescription of AL occurs even when the drug is available and in countries such as Zambia, patients are not required to pay for antimalarial drugs. Therefore, the cost to the patient cannot be an impediment to AL being prescribed to the patients. In Malawi where the policy change was made to adopt SP and not ACT, only 37.4% of children received appropriate treatment[39] whereas in Uganda before the policy change to ACTs was implemented, only 40% were prescribed the recommended anti-malarials[40]. Therefore it seems that health workers blame the ‘system’ in which they work instead of seeing themselves as part of the solution, when in fact, as health workers they are part of the health system and their actions do impact on malaria case management [27,37,41,42]. The under utilisation of diagnostic results and inappropriate prescription of anti-malarials reported in this study and other studies has also been reported among private clinics in Kenya [43]and pharmacies in Ivory Coast[44]. Therefore, this illustrates how widespread this problem is and how it may be a contributor to slowing progress in reducing malaria related mortality.

Innovative approaches on how to improve health worker adherence to treatment guidelines are required in order to contribute to better malaria case management at lower level health facilities. It is important to develop mentoring programmes for health workers where they begin to see themselves as part of the solution of delivering effective case management, otherwise the full benefits and health outcomes of implementing effective malaria case management may not be realised[37].

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this study was supported by The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation support to PATH for the Malaria Control Evaluation Partnership for Africa (MACEPA) project, Grant Number: OPP1013468. We thank Dr. Peter Mwaba, the Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Health Zambia. We wouldalso like to thank the District Health Offices for consistently providing data. Thank you to the programme officers at National Malaria Control Centre and the district staff for their support.

Comments

Background

This article describes a retrospective review of malaria case management in four districts in Zambia. Past evaluations have demonstrated deficiencies in the use of diagnostics for malaria and the proper prescription of artemisinin-based combination therapy.

Research frontiers

Zambia rapidly scaled up the availability and use of RDTs for malaria between 2004 and 2006. This paper describes how well these tests were being used a few years later in 2008 and the effect of specific factors (such as type of health care provider and malaria in-service training) on the proper use of diagnostics and prescription of AL.

Related reports

The findings described in this research are moderately different from those of a previous evaluation of malaria case management practices in Zambia (Hamer DHet al.(2006). In the current study, 715 of patients were parasitologically confirmed whereas in the earlier one, only 27% had a diagnostic test done. This suggest that the use of malaria diagnostics, either RDT or microscopy, has improved between 2006 and 2008 in Zambia.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This is far from the innovative research. It is a practical retrospective review of clinic records in a small number of health centers (n=12). However, the selection of health centers in four different areas of the country with different levels of malaria transmission helps to make the results more generalizable.

Applications

The findings reported by Chanda-Kapataet al. demonstrate continued problems with malaria case management in Zambia. In addition to demonstrating a need for further strengthening of the use of malaria diagnostics, there is also a need to improve the use of AL instead of SP. Innovative interventions to improve malaria case management are urgently needed.

Peer review

This is a relatively small, retrospective study of malaria case management practices in Zambia. It highlights several aspects that require attention including the use of diagnostics for all patients, decreasing the use of SP for malaria test confirmed cases, eliminating the use of anti-malarial drugs for patients WHO test negative for malaria, and assuring that all patients with confirmed malaria receive treatment.

[1] World Health Organisation. Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. [Online] Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/ publications/2010/9789241547925_eng.pdf. [Accessed on 27 September, 2013].

[2] World Health Organisation. World malaria report 2010. Geneva: Switzerland; 2010. [Online] Available from: http://www.who. int/malaria/world_malaria_report_2010/en/. [Accessed on 27 September, 2013].

[3] Central Statistical Office. Zambia demographic health survey 2007. Lusaka, Zambia: Central Statistical Office; 2009. [Online] Available from: http://countryoffice.unfpa.org/zambia/drive/2007_ zdhs_final_report.pdf. [Accessed on 27 September, 2013].

[4] Masiye F, Chitah BM, Chanda P, Simeo F. Removal of user fees at primary health care facilities in Zambia: a study of effects on utilisation and quality of care. Zambia: Department of Economics, University of Zambia; 2008. [Online] Available from: http://www. equinetafrica.org/bibl/docs/Dis57FINchitah.pdf. [Accessed on 27 September, 2013].

[5] World Health Organization. Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Online] Available from: http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/ atoz/9789241547925/en/. [Accessed on 10 December, 2013].

[6] Ministry of Health. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of malaria in Zambia. 3rd ed. Lusaka: Ministry of Health; 2010.

[7] Haque R, Thriemer K, Wang Z, Sato K, Wagatsuma Y, Salam MA, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of artemether-lumefantrine for the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Bangladesh. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2007; 76(1): 39-41.

[8] Chanda P, Masiye F, Chitah BM, Sipilanyambe N, Moonga BH, Banda P, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of artemether lumefantrine for treatment of uncomplicated malaria in Zambia. Malar J 2007; 6: 21.

[9] Chanda P, Castillo-Riquelme M, Masiye F. Cost-effectiveness analysis of the available strategies for diagnosing malaria in outpatient clinics in Zambia. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2009; 7: 5.

[10] Ministry of Health. Zambia national malaria indicator survey. National Malaria Control Centre, Lusaka, Zambia: Ministry of Health; 2008. [Online] Available from: http://nmcc.org.zm/files/ ZambiaMIS2008Final_000.pdf. [Accessed on 27 September, 2013].

[11] Central Statistical Office, Central Board of Health, and ORC Macro. Zambia demographic and health survey 2001-2002. Calverton, Maryland, USA: Central Statistical Office, Central Board of Health, and ORC Macro; 2003. [Online] Available from: http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR136/FR136.pdf. [Accessed on 27 September, 2013].

[12] Ministry of Health. Zambia national malaria indicator survey 2006. Lusaka, Zambia: Ministry of Health; 2006. [Online] Available from: http://nmcc.org.zm/files/2006_Zambia_Malaria_Indicator_Survey. pdf. [Accessed on 27 September, 2013].

[13] Ministry of Health. Zambia national malaria indicator survey 2008. Lusaka, Zambia: Ministry of Health; 2009. [Online] Available from: http://nmcc.org.zm/files/ZambiaMIS2008Final.pdf. [Accessed on 27 September, 2013].

[14] Chizema-Kawesha E, Miller JM, Steketee RW, Mukonka VM,Mukuka C, Mohamed AD, et al. Scaling up malaria control in Zambia: progress and impact 2005-2008. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2010; 83(3): 480-488.

[15] Ministry of Health. Assessment of the health information system in Zambia. Lusaka: Ministry of Health; 2007. [Online] Available from: http://nmcc.org.zm/files/ZambiaHISAssessmentReport.pdf. [Accessed on 27 September, 2013].

[16] Gouwsa E, Bryceb J, Pariyoc G, Schellenbergd JA, Amarale J, Habicht JP. Measuring the quality of child health care at firstlevel facilities. Soc Sci Med 2005; 61: 613-625.

[17] Chanda P, Hamainza B, Mulenga S, Chalwe V, Msiska C, Chizema-Kawesha E. Early results of integrated malaria control and implications for the management of fever in under-five children at a peripheral health facility: a case study of Chongwe rural health centre in Zambia. Malar J 2009; 8: 49.

[18] Chanda P, Chipeta J, Chimutete M, Kango M, Ndhlovu M, Msiska C, et al. An assessment of management of severe malaria in Zambia health facilities. Med J Zambia 2007; 34: 92-97.

[19] Chanda P. The quality of malaria case management and the perceived value of malaria risk reduction in four districts in Zambia[dissertation]. Italy: University of Camerino; 2011.

[20] Masaninga F, Chanda E, Chanda-Kapata P, Hamainza B, Masendu HT, Kamuliwo M, et al. Review of the malaria epidemiology and trends in Zambia. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2012; 3: 89-94.

[21] National Malaria Control Centre. Zambia national malaria control programme: enumeration activities annual summary report. Lusaka: National Malaria Control Centre; 2009. [Online] Available from: http://nmcc.org.zm/files/02_EnumerationSummary20091110. pdf. [Accessed on 27 September, 2013].

[22] Ministry of Health. Malaria Programme Review 2010. Lusaka: Ministry of Health; 2011. [Online] Available from: http://nmcc. org.zm/files/MalariaReport2011September.pdf. [Accessed on 27 September, 2013].

[23] Ntoburi S, Hutchings A, Sanderson C, Carpenter J, Weber M, English M, et al. Development of paediatric quality of inpatient care indicators for low-income countries-a Delphi study. BMC Pediatr 2010; 10: 90.

[24] Hamer DH, Ndhlovu M, Zurovac D, Fox M, Yeboah-Antwi K, Chanda P, et al. Improved diagnostic testing and malaria treatment practices in Zambia. JAMA 2007; 297: 2227-2231.

[25] Zurovac D, Ndhlovu M, Sipilanyambe N, Chanda P, Hamer DH, Simon JL, et al. Paediatric malaria case management with artemether-lumefantrine in Zambia: a repeat cross sectional study. Malar J 2007; 6(1): 31.

[26] Moody A. Rapid diagnostic tests for malaria parasites. Clin Microbio Rev 2002; 15(1): 66-78.

[27] Kyabayinze DJ, Asiimwe C, Nakanjako D, Nabakooza J, Counihan H, Tibenderana JK. Use of RDTs to improve malaria diagnosis and fever case management at primary health care facilities in Uganda. Malar J 2010; 9: 200.

[28] Sserwanga A, Harris JC, Kigozi R, Menon M, Bukirwa H, Gasasira A, et al. Improved malaria case management through the implementation of a health facility-based sentinel site surveillance system in Uganda. PLoS One 2011; 6(1): e16316.

[29] Wongsrichanalai C, Barcus MJ, Muth S, Sutamihardja A, Wernsdorfer WH. A review of malaria diagnostic tools: microscopy and rapid diagnostic test (RDT). Am J Trop Med Hyg 2007; 77(6 Suppl): 119-127.

[30] White NJ. Antimalarial drug resistance. J Clin Invest 2004; 113(8): 1084-1092

[31] Central Statistical Office, Zambia. 2000 Census Report. Lusaka: Central Statistical Office, 2000. [Online] Available from: http:// www.zamstats.gov.zm/about_us/abt_publications.htm. [Accessed on 27 September, 2013].

[32] Moonasar D, Goga AE, Frean J, Kruger P, Chandramohan D. An exploratory study of factors that affect the performance and usage of rapid diagnostic tests for malaria in the Limpopo Province, South Africa. Malar J 2007; 6: 74.

[33] Bisoffi Z, Sirima BS, Angheben A, Lodesani C, Gobbi F, Tinto H, et al. Rapid malaria diagnostic tests vs. clinical management of malaria in rural Burkina Faso: safety and effect on clinical decisions. A randomized trial. Trop Med Int Health 2009; 14(5): 491-498.

[34] Nomhwange TI, Whitty CJ. Diagnosis of malaria in children’s outpatient departments in Abuja, Nigeria. Trop Doct 2009; 39(2): 90-92.

[35] Zurovac D, Rowe AK, Ochola SA, Noor AM, Midia B, English M, et al. Predictors of the quality of health worker treatment practices for uncomplicated malaria at government health facilities in Kenya. Int J Epidemiol 2004; 33(5): 1080-1091.

[36] Osterholt DM, Rowe AK, Hamel MJ, Flanders WD, Mkandala C, Marum LH, et al. Predictors of treatment error for children with uncomplicated malaria seen as outpatients in Blantyre district, Malawi. Trop Med Int Health 2006; 11(8): 1147-1156.

[37] Wasunna B, Zurovac D, Goodman CA, Snow RW. Why don’t health workers prescribe ACT? A qualitative study of factors affecting the prescription of artemether-lumefantrine. Malar J 2008; 7: 29.

[38] Derua YA, Ishengoma DR, Rwegoshora RT, Tenu F, Massaga JJ, Mboera LE, et al. Users’ and health service providers’ perception on quality of laboratory malaria diagnosis in Tanzania. Malar J 2011; 10(1): 78.

[39] Holtz TH, Kachur SP, Marum LH, Mkandala C, Chizani N, Roberts JM, et al. Care seeking behaviour and treatment of febrile illness in children aged less than five years: a household survey in Blantyre District, Malawi. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2003; 97(5): 491-497.

[40] Nshakira N, Kristensen M, Ssali F, Whyte SR. Appropriate treatment of malaria? Use of antimalarial drugs for children’s fevers in district medical units, drug shops and homes in eastern Uganda. Trop Med Int Health 2002; 7(4): 309-316.

[41] Zurovac D, Rowe AK. Quality of treatment for febrile illness among children at outpatient facilities in sub-Saharan Africa. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 2006; 100(4): 283-296.

[42] Achan J, Tibenderana J, Kyabayinze D, Mawejje H, Mugizi R, Mpeka B, et al. Case management of severe malaria - a forgotten practice: experiences from health facilities in Uganda. PLoS One 2011; 6(3): e17053.

[43] Abuya TO, Molynuex CS, Orago AS, Were S, Marsh V. Quality of care provided to febrile children presenting in rural private clinics on the Kenyan coast. Afr Health Sci 2004; 4(3): 160-170.

[44] Kiki-Barro CP, Konan FN, Yavo W, Kassi R, Menan EI, Djohan V, et al. [Antimalaria drug delivery in pharmacies in non-severe malaria treatment. a survey on the quality of the treatment: the case of Bouaké (C?te d’Ivoire)]. Sante 2004; 14(2): 75-79. French.

10.12980/APJTB.4.2014C153

*Corresponding author: Pascalina Chanda-Kapata, Ministry of Health, Headquarters, Ndeke House. P.O. Box 30205, Lusaka, Zambia.

E-mail: pascykapata@gmail.com

Tel: 260 977 879101

Foundation Project: Supported by The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation support to PATH for the Malaria Control Evaluation Partnership for Africa (MACEPA) project, Grant Number: OPP1013468.

Article history:

Received 12 Apr 2014

Received in revised form 18 Apr, 2nd revised form 24 Apr, 3rd revised form 29 Apr 2014

Accepted 20 May 2014

Available online 28 Jun 2014

Methods:This study was a retrospective evaluation of the quality of malaria case management at health facilities in four districts conveniently sampled to represent both urban and rural settings in different epidemiological zones and health facility coverage. The review period was from January to December 2008. The sample included twelve lower level health facilities from four districts. The Pearson Chi-square test was used to identify characteristics which affected the quality of case management.

Results:Out of 4 891 suspected malaria cases recorded at the 12 health facilities, more than 80% of the patients had a temperature taken to establish their fever status. About 67% (CI9566.1-68.7) were tested for parasitemia by either rapid diagnostic test or microscopy, whereas the remaining 22.5% (CI9521.3.1-23.7) were not subjected to any malaria test. Of the 2 247 malaria cases reported (complicated and uncomplicated), 71% were parasitologically confirmed while 29% were clinically diagnosed (unconfirmed). About 56% (CI9553.9-58.1) of the malaria cases reported were treated with artemether-lumefantrine (AL), 35% (CI9533.1-37.0) with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine, 8% (CI956.9-9.2) with quinine and 1% did not receive any anti-malarial. Approximately 30% of patients WHO were found negative for malaria parasites were still prescribed an anti-malarial, contrary to the guidelines. There were marked inter-district variations in the proportion of patients in WHOm a diagnostic tool was used, and in the choice of anti-malarials for the treatment of malaria confirmed cases. Association between health worker characteristics and quality of case malaria management showed that nurses performed better than environmental health technicians and clinical officers on the decision whether to use the rapid diagnostic test or not. Gender, in service training on malaria, years of residence in the district and length of service of the health worker at the facility were not associated with diagnostic and treatment choices.

Conclusions:Malaria case management was characterised by poor adherence to treatment guidelines. The non-adherence was mainly in terms of: inconsistent use of confirmatory tests (rapid diagnostic test or microscopy) for malaria; prescribing anti-malarials which are not recommended (e.g. sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine) and prescribing anti-malarials to cases testing negative. Innovative approaches are required to improve health worker adherence to diagnosis and treatment guidelines.

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine2014年6期

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine2014年6期

- Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine的其它文章

- Study of the efficacy of a Wheaton coated bottle with permethrin and deltamethrin in laboratory conditions and a WHO impregnated paper with bendiocarb in field conditions

- Pharmacognostical study and establishment of quality parameters of aerial parts of Costus speciosus-a well known tropical folklore medicine

- Hepatocurative potential of Vitex doniana root bark, stem bark and leaves extracts against CCl4-induced liver damage in rats

- In vitro α-amylase inhibitory activity and in vivo hypoglycemic effect of methanol extract of Citrus macroptera Montr. fruit

- Antimicrobial activity of some essential oils against oral multidrugresistant Enterococcus faecalis in both planktonic and biofilm state

- Phytochemical and biological studies of Butia capitata Becc. leaves cultivated in Egypt