Erasable/Inerasable L1 Transfer in Interlanguage Phonology: An Optimality Theory Analysis of /a?n/and Sentence Stress in Chinese Learners of English

fan Yi

Peking University

Abstract: The areas affected by the L1 transfer to L2, such as phonotactics and stress, appear to have different degrees of erasability through training and practice. This paper attempts a theoretical analysis to account for empirical observations of L1 transfer in diphthong-coda coalescence and in sentence stress for Chinese learners of English in an American accent training course. Using the framework and tableau method of Optimality Theory (Prince and Smolensky 1993), the phonological paradigm that views languages’ differences as symptomatic of differences in rankings of a set of universal violable constraints, this paper posits the underlying ranking at work in (a) the segmental case where [a?] is the observed output for /a?n/; (b) the suprasegmental case where no stress contrast is observed for a pair of phonologically similar sentences with contrastive stress. It is argued that, in the segmental case, the coalescence of the second vowel of a diphthong with an alveolar nasal coda results from the high ranking of markedness constraints, including Complex Syllable; and in the suprasegmental case, sentence stress is greatly affected by changes in the ranking of the constraint culminativity.Aside from shedding light on the understudied issue of diphthong-coda coalescence, this research also contributes to the discussion of the comparative erasability of L1 transfer for the two areas and demonstrates how a deduction-based theoretical method may actually have practical implications for guiding the design of L2 teaching methodology of English pronunciation as well as for promoting native English speakers’ clearer understanding of Chinese learners of English on the global stage.

Keywords: Chinese ESL learners, coalescence, diphthong, second language acquisition, sentence stress, Optimality Theory

Introduction

The term “interlanguage” (Selinker 1972) refers to the linguistic systems of L2 learners,conceived of as distinct from both the L1 and the L2 systems. By recognizing that L2 learners’ language systems are as fully developed and rule-governed as any language system, the interlanguage theory offers a dynamic, pragmatic perspective on these systems’ nature and changes,more so than the earlier contrastive analysis theory, which focuses on explaining L2 learners’ error production solely through observable differences between the L1 and the L2. In the decades since Selinker’s first coining of “interlanguage,” SLA researchers have attempted to flesh out the theory,such as Major (2001), whose Ontogeny Phylogeny model posits that L1, L2, and Universal Grammar(UG) all have effects on the interlanguage, but in a specific order at different stages of the acquisition of L2. However, recognizing the idiolect status of interlanguage also raises some difficulties: how exactly do we characterize it, and how do we generalize various kinds of interlanguage formed from different L1 and L2 contexts? Pursuing the answers to these questions may contribute to refining pedagogical methods from an educational perspective, illuminating underlying mechanisms of language interactions from a theoretical perspective, and improving native speakers’ understanding of interlanguage traits for better communications from a social perspective.

Optimality Theory (OT), originally formulated by Prince and Smolensky in 1993, presents a flexible, constraint-based approach that can show clearly what kind of influences L1, L2, and UG can have on the idiolect. This framework advances the following procedure: for an input, potential candidates are generated and subjected to evaluation by a set of constraints that are universal, which then determines the optimal output. In general, constraints fall under two categories: faithfulness constraints, which are concerned with preserving traits of the input, and markedness constraints, which are concerned with the “preferred shape” of surface representations (Iosad 2018). While the ranking of constraints essentially encodes properties specific to the language, OT can account for the fact that interlanguage forms can have phonological elements that seem to be unpredictable from either L1 or L2 surface rules because low-ranked constraints can exert influence on the output, in a situation of the “emergence of the unmarked” (McCarthy & Prince 1994). Furthermore, the development of the interlanguage of ESL speakers over time could be modeled from an OT perspective as migration of constraint rankings: at first, any highly ranked markedness constraints that are characteristic of L1 retain their prominence since L1 is the initial base upon which the interlanguage develops; then, as L2 input increases, learners proceed to rerank constraints, and faithfulness constraints and markedness constraints highly ranked in L2 rise in prominence. The dynamic system of this reorganization may find a stable equilibrium before approaching the native L2 ranking.

Despite the many possible advantages OT may offer for explaining interlanguage issues, the application of this framework remains at a nascent stage in L2 phonological acquisition research.Currently, there does not yet exist an extensive body of OT research concerning the interlanguage of L1 Mandarin Chinese and L2 English specifically, but evidence from research on the interlanguage of L2 English with various other L1 support the viability of such an approach in general, particularly in regards to phonotactics - c.f. Broselow, Chen, and Wang (1998) on obstruent codas of Chinese ESLs,also further discussed in section 3.1.1 of this paper; Hancin-Bhatt (2000) on codas in Thai ESLs; Bunta and Major (2004) on vowels of Hungarian ESLs; Cardoso (2006) on voiceless codas of Brazilian Portuguese ESLs; Chan (2010) on initial consonant clusters of Cantonese ESLs; Nguyen (2019) on final consonant clusters of Vietnamese ESLs; Al-Yami and Al-Athwary (2021) on consonant clusters of Saudi ESLs. Additionally, OT research has been conducted on the phonotactics in the interlanguage of L1 English with L2 of other languages, e.g., Zhang (2016) on L2 Mandarin; Guimaraes (2017) on L2 Brazilian Portuguese. This paper extends this OT L2 phonotactics research tradition by contributing new research on the coalescence of diphthongs and consonants in the interlanguage of Chinese ESLs,which is an understudied area. This paper also engages in conversation with coalescence research in OT outside of the interlanguage context, such as Zaleska (2020).

When moving beyond the lexical level, the interface of syntax and phonology is involved, so more variables need to be considered. For instance, sentence stress has attracted numerous studies in terms of specific languages. Selkirk (1995; 2000) theorizes the interaction of constraints on the stress in prosodic phrasing, highlighting focus as well as sentence stress in default English sentences. Ishihara (2011)examines the role of focus as independent from prosodic phrasing in Japanese, which leads to multiheaded or headless prosodic phrases. Feldhausen (2016) uses Stochastic Optimality Theory to account for inter-speaker variation in an examination of clitic left dislocations in Spanish prosody. However,there have been very few studies on sentence stress of the interlanguage of speakers whose L1 is a tonal language, and L2 is a stress-timed language. But in fact, sentence stress is exactly the area where these learners make the most noticeable errors. For example, Nguyn, Ingram, and Pensalfini (2008) observe how prosodic transfer from L1 Vietnamese has affected learners’ ability to produce and perceive focus in noun phrases in the phrase prosody of English. Ji and Liu (2021) investigate Chinese ESLs’ sentence stress errors. This paper independently confirms some theoretical conclusions of Ji and Liu regarding Align constraints, but while Ji and Liu examine stress using an excerpt of textbook sentences as the test case, this paper directly examines a matched pair of phonologically similar sentences.

Thus, there are two focuses of study in this paper based on the observations of Chinese learners of English in a training course: first, diphthong interactions with nasal codas, which is the aspect that is most resistant to change; second, sentence stress in relation to constraints regarding new information and focus, which is the aspect that has very noticeable change. Therefore, the direction shaping the investigations of this paper is to visualize the factors behind the problems made by Chinese learners of English. By studying the most difficult and easiest aspects of the interlanguage of some students, some recommendations can be made about the balance of content focus in second language pronunciation classes. Furthermore, as increasing numbers of Chinese learners of English engage in academic and business pursuits internationally, the traits of interlanguage of Chinese learners are also worthy of being brought to the attention of native English speakers and other global audiences to facilitate better understanding and smoother international communications.

Context on Empirical Observations

The empirical observations for which the theoretical analysis of this paper attempts to explain originate from a data corpus formed during an observational study of Chinese university students from diverse majors and different years of graduating classes who signed up for an American accent training course. These students attended the training course with the intention of pursuing educational or vocational opportunities abroad in the future. The classes incorporated both segmental and suprasegmental training, emphasizing how to pronounce vowels and consonants correctly and how to produce complicated onset and coda clusters, as well as explicitly examining sentences and sentence stress. Prior to the start of the classes, students were asked to submit a voice recording of their reading of a diagnostic sheet of sample words and sentences. Throughout each week, students submitted homework assignments of their recorded readings of assigned sentences and paragraphs. The course concluded with the students submitting a recording of them rereading the diagnostic assignment. Aside from the sound files from these assignments, observations were also drawn from student performance and participation in class.

From the variety of information available for examination, the aspect selected for analysis was the one that appeared to be most resistant to change across all levels of English proficiency or amount of experience studying English, and the aspect that appeared to have the most change across the students.Although the errors in these categories appear to result from L1 interference, sentence stress is an area where this interference could be overcome. Specifically, the items examined are the word “down” and the underlined portion of these sentences: (a) How many pets do you have? I have two. (b) I study hard because I have to.

Theoretical Analysis of Phonotactics and Stress

Part 1: Phonotactics

The Case of “Down”

“Down” was the most frequently mispronounced word in the diagnostic test as well as the end of the course follow-up. To evaluate this situation, first, a previous study examining obstruent codas is discussed in depth, then a new ranking system accommodating nasal codas is built from that study’s ranking basis, and then the discussion is expanded to other diphthongs.

Obstruent Codas: A Summary and Evaluation of Broselow, Chen, and Wang (1998)

Broselow, Chen, and Wang’s 1998 paper analyzes Chinese native speakers’ simplification of English forms with obstruent codas. Through OT, they reveal how L2 learners’ strategies reflected the influence of previously low-ranked markedness constraints in the native language that now rose high enough in the interlanguage ranking to make a difference.

From a preliminary analysis, they note that participants resorted to epenthesis, deletion, or devoicing when faced with obstruent codas, which are not seen in Chinese. They posit the following rankings for a generalization of the interlanguage of each situation (lettering of rankings mine, for ease of distinction and reference):

Ranking a - simple deletion: No Obs Coda >> Dep >> Max

Ranking b - simple epenthesis: No Obs Coda >> Max >> Dep

Ranking c - simple devoicing: No Voiced Obs Coda >> Max, Dep >> Ident (voi) >> No Obs Coda

There was also some inconsistency of strategies for individual participants, some of which Broselow et al. attribute to the malleable nature of interlanguage systems, but some of which they account for by bringing to the fore a particular markedness constraint, Wd Bin (Word Binarity), that favors words containing two syllables.

Then, they incorporate Wd Bin in positing two possible ranking systems to account for certain inconsistent participants: one which results in epenthesis if the input form is monosyllabic, but in deletion, if it is disyllabic:

Ranking d: No Obs Coda >> Max, Dep >> Wd Bin

And another, which results in epenthesis for monosyllabic inputs but devoicing for disyllabic inputs:

Ranking e: No Voiced Obs Coda >> Wd Bin >> Max, Dep >> Ident (voi), No Obs Coda

Whileranking eis an interesting hypothesis and appears to present an explanation of occasional devoicing, I find its validity as an interlanguage grammar ranking doubtful and to be challenged. After all, the ranking of Wd Bin above faithfulness constraint Dep would entail that monosyllabic inputs with no codas or with sonorant codas would also have winning outputs with epenthesis. In fact, these occurrences are next to none, based on my data. How to accommodate and repair this ranking would be something to explore at a different time. Now, I would like to useranking das a basis to build upon a more detailed ranking to accommodate some phenomena in nasal codas and also complex codas with both a nasal and an obstruent.

Extension to Nasal Codas

The particular subset of codas in Broselow et al.’s (1998) investigation, obstruent codas, presents a complex case in interlanguage phonology because obstruent codas are not observed or deduced to be in any underlying forms in Chinese. On the other hand, the Chinese language does have two nasal codas:the alveolar nasal [n] and the velar [?]. Thus, it might seem, at first glance, that if an input contained such a simple allowed nasal coda, then the winning output coda should be preserved and epenthesis unnecessary: for example, an input of /s?n/ would be predicted to be mapped to an output of [s?n]; an input of /da?n/ would be predicted to be mapped to an output of [da?n].

In fact, while the output of soon [s?n] for /s?n/ was indeed generally seen, the overwhelming majority of students I observed exhibited an output of [da?] for /da?n/. The discrepancy shows that there are some constraints at work in the interlanguage whose effects might not be readily deduced from observing obstruent codas alone. This manifests in significant interactions between the vowels and the codas: coalescence of the second vowel of a diphthong with the alveolar nasal coda.

Here, it is also appropriate to briefly describe the phonotactics of diphthongs in the native Chinese. While diphthongs do occur, they do not appear in the environment of nasal codas.Furthermore, while /a?/ does not exist in Chinese, /au/, which is very close, does, which the participants often use instead in their interlanguage. However, for the purposes of this paper, I have notated any production of [a] as [a?] for simplicity. The one-to-one correspondence can be seen as an allophone issue of phonetics that does not erase any contrasts, much like the American pronunciation of /a?/ can actually be /??/.)

The constraints that are relevant to this case are as follows:

Markedness constraints:

● Complex Syllable: assign one violation mark for every complex syllable (μμμ). In this case, a diphthong and a nasal consonant would constitute a complex syllable.

● No Obs Coda: assign one violation mark for an obstruent coda (from Broselow et al.).

● Onset: assign one violation mark for an onset-less syllable. (In this case, its inclusion is necessitated by a hypothetical losing candidate where a diphthong is parsed as two syllables.)

Faithfulness constraints:

● Ident: assign one violation mark for each input segment changed in the output.

● Max: assign one violation mark for each input segment deleted in the output.

● Ident (dorsal): assign one violation mark for every dorsal feature altered from the input. Dorsal includes features, such as the place of a vowel as well as that of a consonant; the back and high features of a vowel would be equivalent to the glottal feature of a consonant.

● Max (dorsal): assign one violation mark for every dorsal feature deleted from the input.

● Linearity: assign one violation mark for disruption of the order of features from the input.

● Uniformity: assign one violation mark for each case of coalescence.

Twelve ranking arguments for these constraints are deduced as follows:

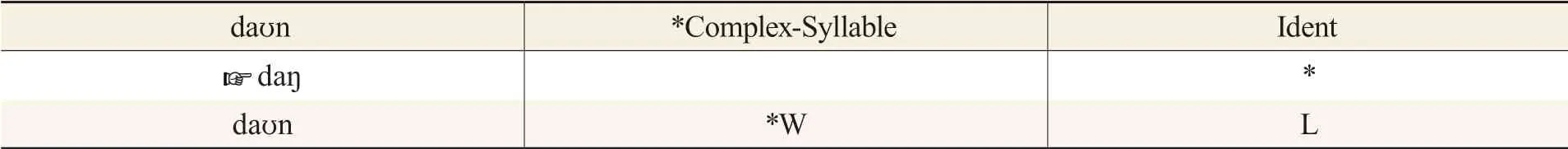

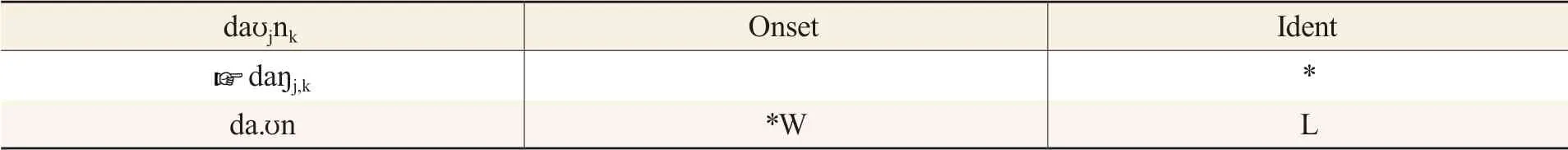

(1) Complex Syllable >> Ident

da?n *Complex-Syllable Ident da? *da?n *W L

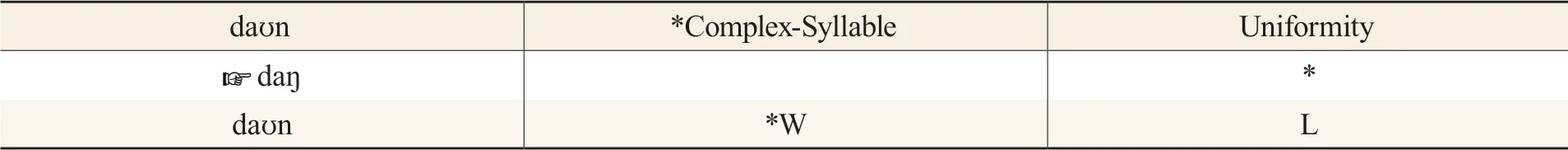

(2) Complex Syllable >> Uniformity

da?n *Complex-Syllable Uniformity da? *da?n *W L

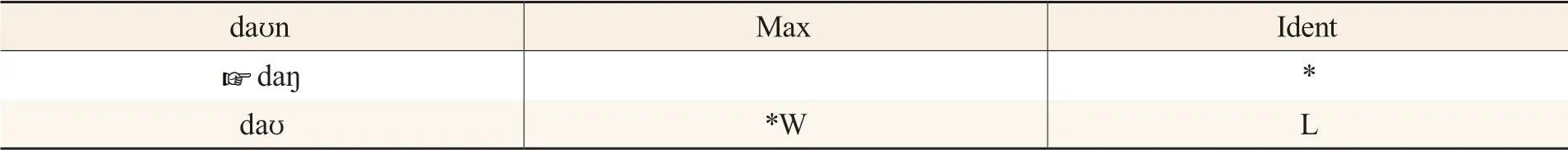

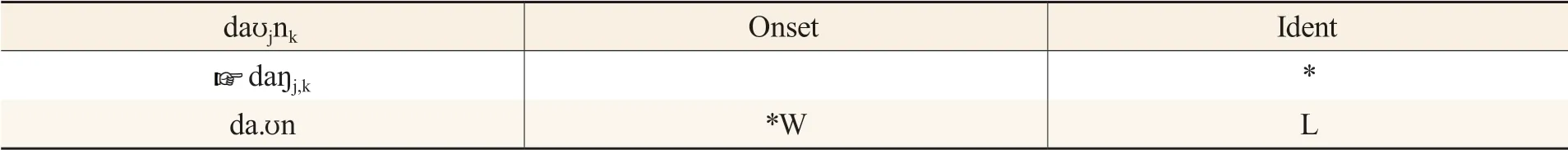

(3) Max >> Ident

da?n Max Ident da? *da? *W L

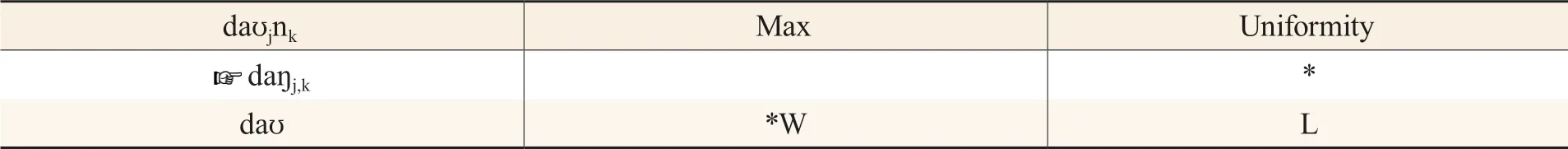

(4) Max >> Uniformity

da?jnk Max Uniformity da?j,k *da? *W L

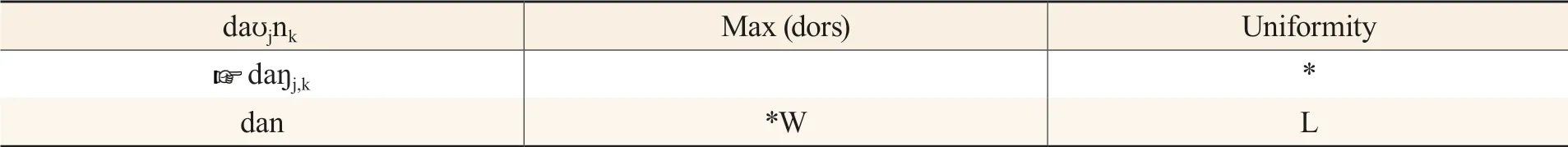

(5) Max (dors) >> Uniformity

da?jnk Max (dors) Uniformity da?j,k *dan *W L

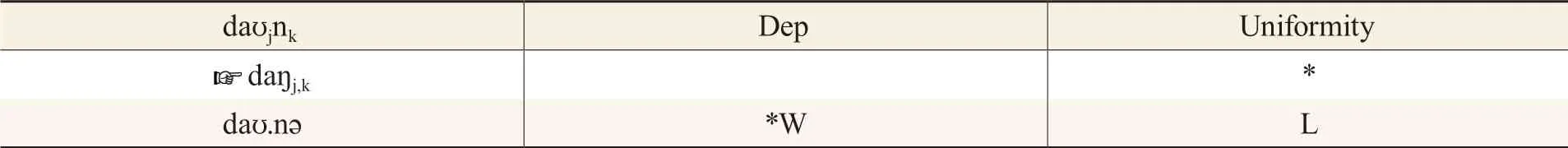

(6) Dep >> Uniformity

da?jnk Dep Uniformity da?j,k *da?.n? *W L

(7) Dep >> Ident

da?n Dep Ident da? *da?.n? *W L

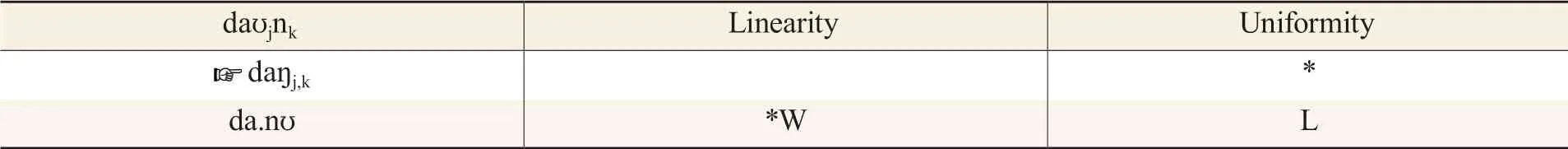

(8) Linearity >> Uniformity

da?jnk Linearity Uniformity da?j,k *da.n? *W L

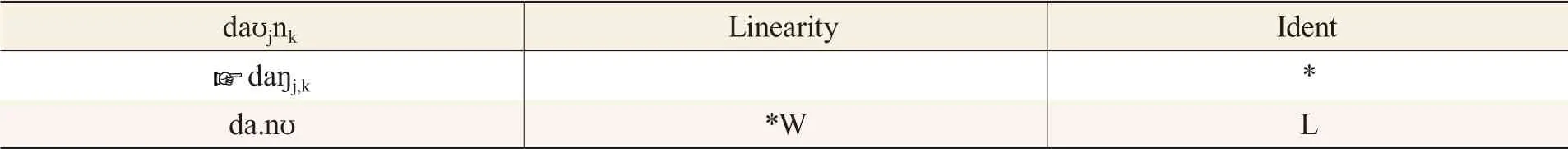

(9) Linearity >> Ident

da?jnk Linearity Ident da?j,k *da.n? *W L

(10) Onset >> Uniformity

da?jnk Onset Ident da?j,k *da.?n *W L

(11) Onset >> Ident

da?jnk Onset Ident da?j,k *da.?n *W L

(12) Dep >> Onset

ɑn Dep Onset ɑn *dɑn *W L

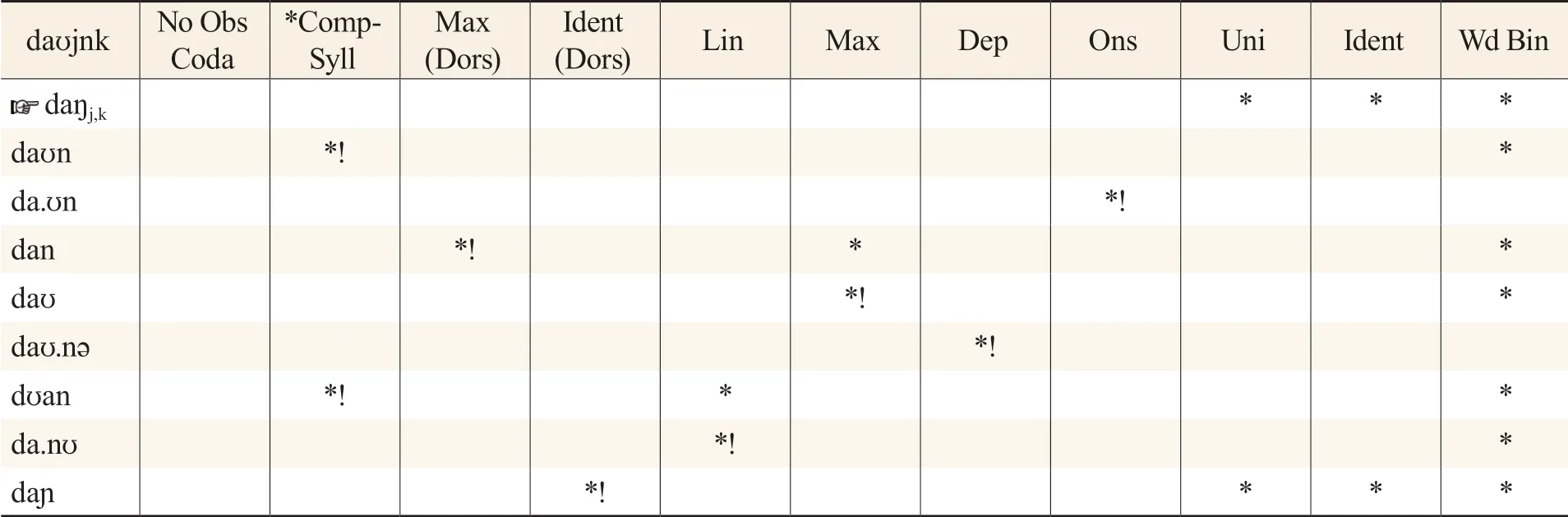

The results of the above ranking arguments are incorporated with the assumptions and rankings ofranking dof Broselow et al. (context-dependent epenthesis or deletion) to produce the following ranking and tableau for [da?n]:

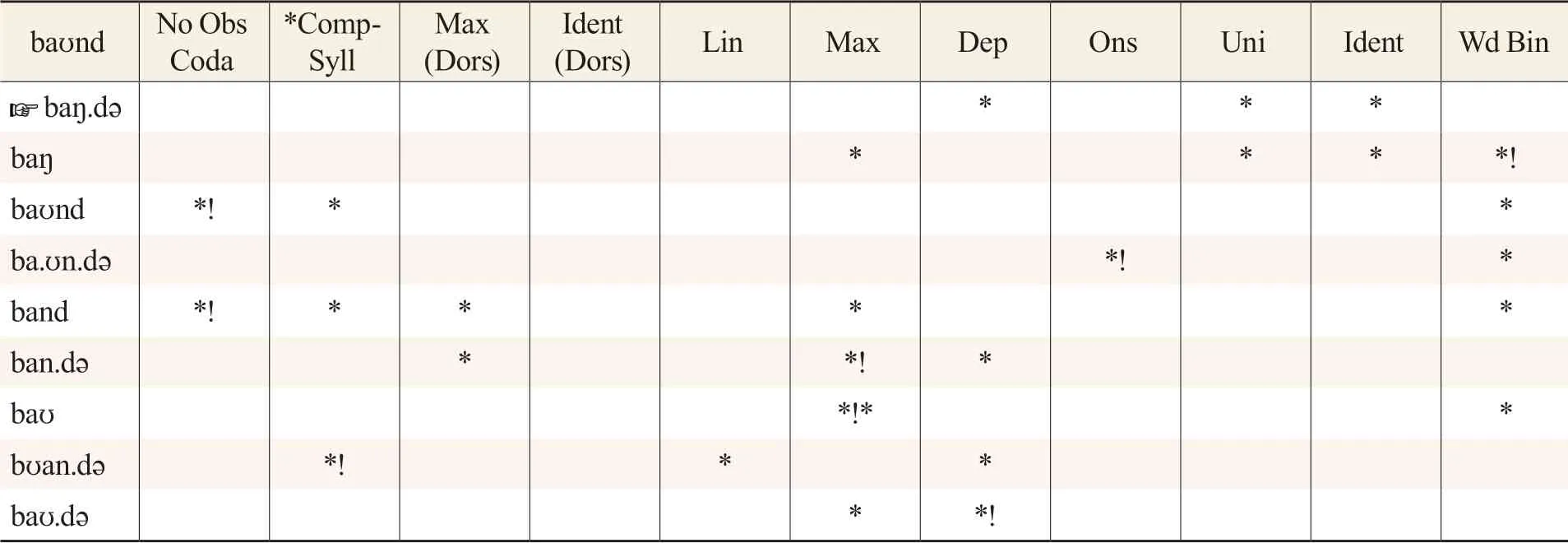

No Obs Coda, Complex Syllable >> Max (dorsal), Ident (dorsal), Linearity, Max, Dep >> Onset >>Uniformity, Ident >> Word Binarity

da?jnk No Obs Coda*Comp-Syll Max(Dors)Ident(Dors) Lin Max Dep Ons Uni Ident Wd Bin da?j,k * * *da?n *! *da.?n *!dan *! * *da? *! *da?.n? *!d?an *! * *da.n? *! *da? *! * * *

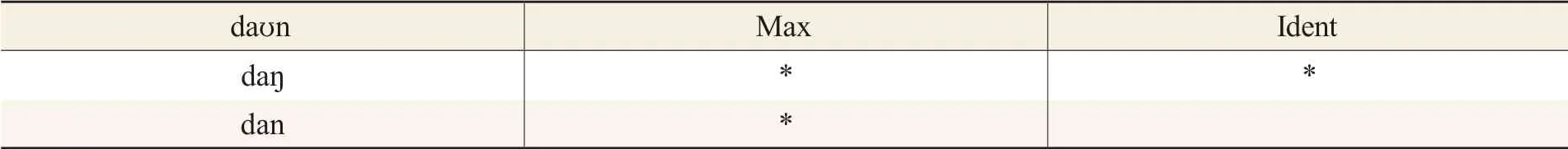

It needs to be clarified that, although it seems that many constraints cannot be ranked in relation to each other, it is still useful to keep a distinct Max (dorsal) from Max as a reminder of what features are coalescing. In a situation where coalescence is not recognized, we would have to mark [da?] for Max,and be subject to the quandary that [dan] is more optimal than [da?]:

da?n Max Ident da? * *dan *

A Further Integration with Broselow et al. (1998): Considering the Monosyllabic Complex Coda Input [ba?nd], and Disyllabic Complex Coda Input “?ba?nd”

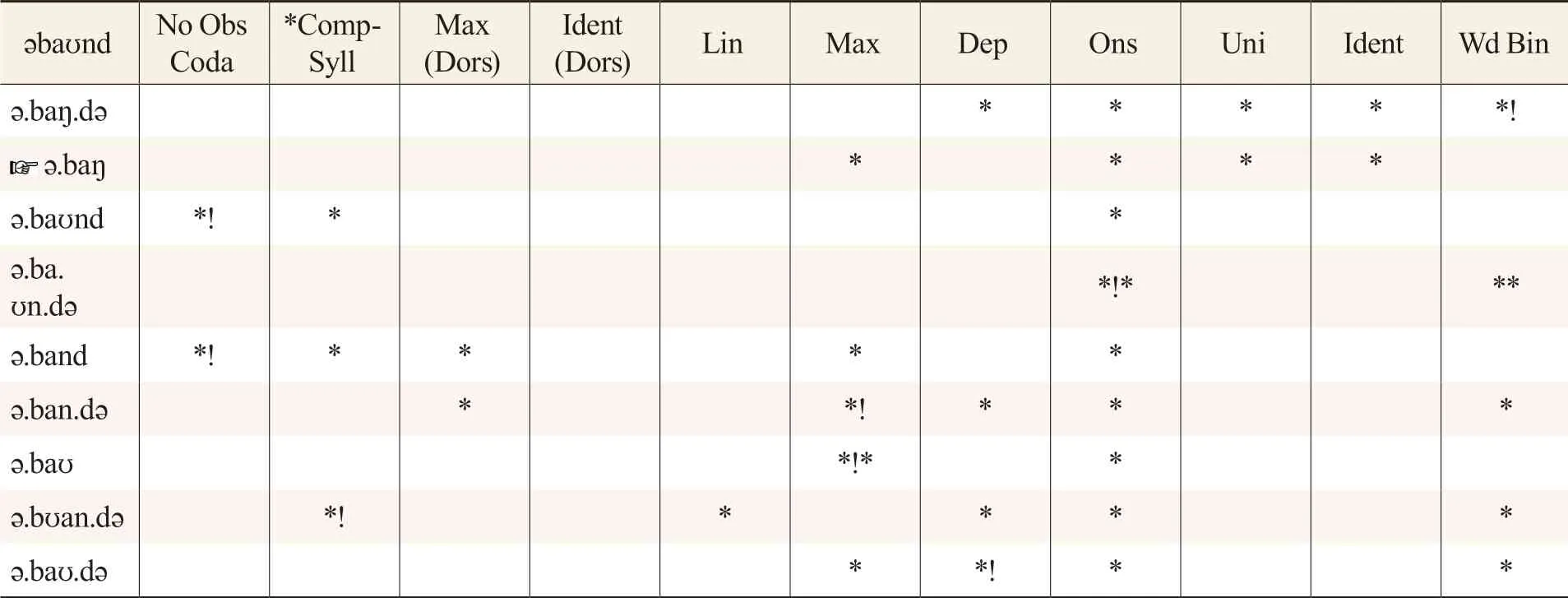

As the next step in the exploration, I now look at the case when there is an input with a complex coda consisting of both a nasal and an obstruent stop. The integrated ranking predicts coalescence with epenthesis for [ba?nd] and coalescence with deletion for “?ba?nd,” as shown as follows:

ba?nd No Obs Coda*Comp-Syll Max(Dors)Ident(Dors) Lin Max Dep Ons Uni Ident Wd Bin ba?.d? * * *ba? * * * *!ba?nd *! * *ba.?n.d? *! *band *! * * * *ban.d? * *! *ba? *!* *b?an.d? *! * *ba?.d? * *!

Note, however, that the above ranking seems unsatisfactory due to the fact that the deciding constraint, Wd Bin, is lower than the mutually unranked Max and Dep, in which the first two candidates each have a violation. Yet, while the first solution is to treat this as evidence that Wd Bin should be ranked higher than Dep, this would also be a problematic move since doing so would mean that an input of a monosyllabic word with no coda or with no complex syllable and a nasal coda, would have as its most favored output, a candidate with epenthesis. This is not observed. How exactly to resolve this point could be a good future exploration.

?ba?nd No Obs Coda*Comp-Syll Max(Dors)Ident(Dors) Lin Max Dep Ons Uni Ident Wd Bin ?.ba?.d? * * * * *!?.ba? * * * *?.ba?nd *! * *?.ba.?n.d? *!* **?.band *! * * * *?.ban.d? * *! * * *?.ba? *!* *?.b?an.d? *! * * * *?.ba?.d? * *! * *

Although there are no neat comparable pairs in the actual recorded data to fully verify this, in the memory of students’ oral responses in class, such patterns seem to exist for some individuals. It would be a good case to test in follow-up studies.

Additional Thoughts on More Situations Involving [a?n]

From the process of doing the OT analysis, some more loose ends and stray thoughts relating to “a?”have been encountered; as they enrich the context and point to future areas of interest, they will also be discussed below.

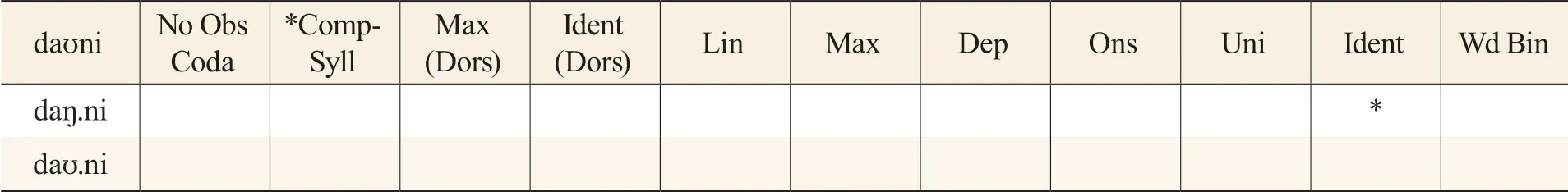

First, what would happen in the case of [a?n] occurring in the middle of a word but not immediately followed by any consonants? For example, among the words tested in my data is the word “downy.”Seeing that it can be parsed in a way that avoids Complex Syll by making the [n] the onset of the second syllable, it might have been expected that the majority of the students would be able to pronounce it as /da?.ni/:

da?ni No Obs Coda*Comp-Syll Max(Dors)Ident(Dors) Lin Max Dep Ons Uni Ident Wd Bin da?.ni *da?.ni

However, it was found that there was a substantial number who continued to pronounce it as /da?.ni/; of these students, all pronounced /da?n/ as /da?/. This phenomenon of defying phonotactics is a case of faithfulness to an identified morphological base, which can be explained by Output-Output Correspondence (Benua 1997; Burzio 2005). Once “down” is recognized as the noun root of the adjective, there is a tendency to retain faithfulness to its standalone pronunciation even in the adjectival form.

Second, are there more reasons why the coalescence might happen? There is interference by English loanwords and proper name translations into Chinese. Yip (1993) discusses the phonology of English loan words in Cantonese, arguing that it is a process of subjecting English inputs to the constraints that define well-formedness in Cantonese. Silverman (1992) points out that in adapting loan words, only part of the signal is detected by a Perceptual Scan, and the result of the scan is registered as the input. I think that knowledge of such transliterated words can be a source of interference with L2 learning of new words that are similar to transliterated ones. In my specific example, proper nouns that include segments of /a?n/, such as “Brown” (布朗) or “Pound” (龐德),are often transliterated in Chinese with characters that have the pinyin “ang,” which is pronounced/a?/. Even when participants can distinguish audio input of /a?/ versus /a?n/, they cannot maintain a consistent distinction in the production of these sounds, showing that the Perceptual Scan is not an issue.

Third, what of [a?] with other nasal codas? Because there does not seem to normally exist in English the combinations of /a?m/ or /a??/, and the sentences and word sets provided to the students to use contained no nonce words, there was no opportunity to see how the students would respond in other contexts of a? + nasal coda.

Fourth, can [a?] to /a?/ be seen in other obscure situations? Students have been observed to render[al] as /a?/, in words such as “call.” Had English contained common words with [aln] sequence, those could have been a test case to see if the winning output might end up being /a?/ as well. (Of course,this would involve more complexity than could be contained in the scope of this paper, but it is an interesting thought nonetheless.)

Extensions: Diphthongs Other Than [a?] + Nasal Codas

The mapping of [da?n] to /da?/ is perhaps distinct enough for those unfamiliar with phonetics to pick up, but an examination of other diphthongs with this constraint ranking sheds light on other details, too.

A diphthong that also ends with “?” is [o?]. Like [a?], it has an analog in Chinese, which is [ou],which similarly cannot exist with nasal codas.

A review of the assignment texts for words incorporating [o?n] resulted in finding “tone”and “phone.” The previous ranking constraints that were built in place to explain [da?n] to /da?/,when applied to [to?n], predict a winning output of /to?/ for the interlanguage. The review of the recordings of the students confirmed that this was indeed a very common output. This output /o?/may not strike a listener as having the same degree of deviance from /o?n/ as /a?/ has compared to /a?n/, possibly because “o” is already a back vowel like “?,” and the change of sound in the diphthong is just a small shift from mid to high position. In contrast, “a?” has a central (or front)to back, low to high shift.

This paper tried to verify this result with the case of “phone.” The most common outputs for it were“f??” as well as “fo?,” which may seem unusual. However, it should be taken into account that it is not uncommon for British English to be the variety taught in Chinese primary schools, and in British English, “phone” would be [f??n]. English taught at beginner levels often focused on concrete nouns of daily life, so it is not unlikely that some students acquired [f??n] as the underlying input, but at a later time, under different tutelage, acquired the more abstract word “tone” as [to?n]. Another equally pertinent factor is that in Chinese, bilabials and labiodentals cannot precede [o?] but can precede [??].Students whose interlanguage was closer to that of the L2 English likely demoted this markedness constraint to be able to produce /fo?/.

Finally, a few other common diphthongs will be summarily touched upon. The diphthong [e?] (which has a Chinese counterpart [ei]); [a?] (counterpart [ai]); [??] (closest equivalent is [uai], which occurs in complementary distribution to [ai]) all have high front vowels as the second part of the diphthong. To subject an input like line [le?n] or lane [la?n] or loin [l??n] to our ranking order implies that coalescence would be again favored, generating a nasal that would preserve the features of +high and +front. Such a candidate would be the palatal nasal [?]. It is important to note that in both English and Mandarin Chinese, [?] does not normally exist, especially not as codas, so *[?] is likely a markedness constraint that plays a role in preventing this coalescence in the majority of cases. It appears that the strategy adopted by many students instead is nasalization of [?] along with the dropping of the velar nasal. This does not violate *[?] and Complex Syllable, and the retention of the nasalization may be considered another facet of coalescence able to occur. This can be a direction for future investigation as well.

Part 2: Sentence Stress

An observation from the experience of teaching sentence stress is that students may not know where to place stress initially. They may place equal stress on every single word, an effect of L1 transfer because in Chinese, sentence stress is minimal due to tone assignments to individual words.When students were taught to recognize that new information and content words should be stressed,their sentence stress patterns improved.

Stress: Definitions

One early conceptualization of stress is by Newman (1946: 172-173), who defines stress in English as the “pitch, vowel quantity, and articulatory force” given to a certain syllable in a word or a certain word in a phrase or a sentence. Schmerling (1976: 4) defines stress as a “subjective impression of prominence.” Cruttenden (1997: 18) uses stress to mean prominence in length, loudness, and pitch. He distinguishes four degrees of stress in English at the constituent level and beyond: 1) primary stress; 2)secondary stress; 3) tertiary stress; 4) unstressed.

From the above definitions, we can see that there is a consensus that stress refers to the perceived prominence in terms of pitch, force, and duration, which is given to a certain syllable in a word or to a certain word in a phrasal constituent or a sentence. It can be categorized into lexical stress (or word stress), phrasal stress (or pitch accent), and sentence stress (or nuclear stress).

Chomsky and Halle (1968) advocate the predictability of sentence stress from words and the structure or structures of the higher orders of the phrasal organization through the algorithm of the Nuclear Stress Rule, which assigns stress to the right-edge word within the boundaries of phrases.Schmerling (1976) examines Chomsky and Halle’s Cyclic Approach to assigning stress using the Nuclear Stress Rule. In every hierarchy, there is one main stress within the phrase. Thus, while words have lexical stress, there is a word that receives prominent stress in a phrase, and a phrase that receives prominent stress in a clause. This simplistic hierarchy is still a good model for instructing Chinese learners of English, who benefit from learning about the placement of stress in different levels of context because of the lack of this hierarchy in Chinese.

Büring (2016: 7) posits an alternative procedure for assigning stress in default sentences that have no context:

Sep 1: Put pitch accents on open class elements; put the minimal number to guarantee that each syntactic phrase contains at least one PA (pitch accent).

Step 2: (a) Delete pitch accents if they are followed by at least one other PA, or alternatively; (b) Add pitch accents on open class elements (OCEs) if they are followed by at least one other PA.

Büring takes open class elements (OCEs) to mean content words, such as nouns, adjectives,and main verbs, and closed class elements (CCEs) to mean function words, such as pronouns,prepositions, determiners, and auxiliaries. Büring’s reduced focus on hierarchies and greater emphasis on distinguishing the classes of elements indicates the recognition of the need to account for morphosyntactic characteristics in assigning stress.

However, another factor also needs to be considered: the information structure of the sentence. Given information is the topic or theme, and new information is comment and rheme. New information is also the undeletable part of words that answers whquestions. Focus is where new and contrastive information lies; it is a grammatical category.Certain structures, such as cleft sentences and passive voice sentences, can foreground fixed focus positions. New information and focus usually invite sentence stress.

Thus, syntactic structures, as well as parts of speech and information structures, are all important factors in determining sentence stress.

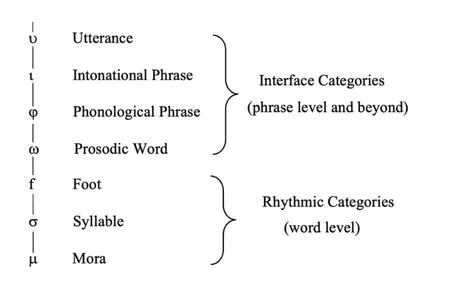

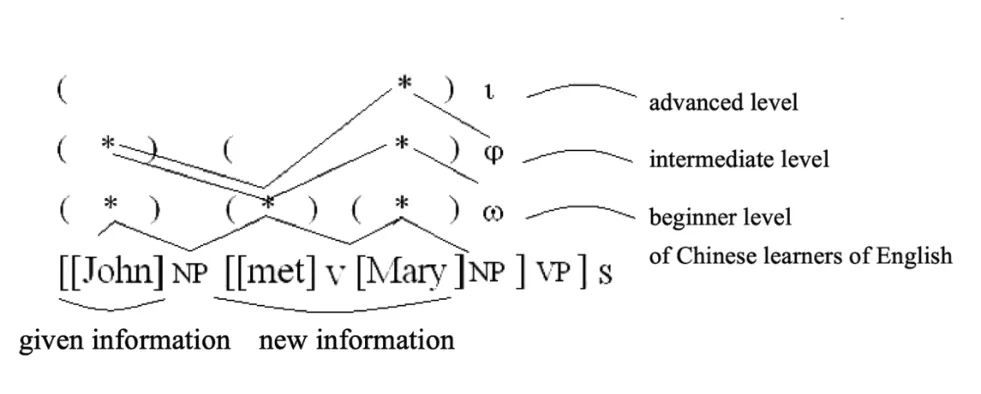

As Figure 1 above shows, there is a hierarchy of phonological units, and sentence stress will interact among interface categories from a prosodic word (ω) and a phonological phrase (φ) to an intonational phrase (ι) and an utterance (υ).

Figure 1: Hierarchy of phonological units (cf. Selkirk 1978; Ito & Mester 2012)

An Examination of Simple Sentence Stress

At this point, it can be said that sentence stress is no simple matter to approach. For this analysis,two simple sentences of 3 words each, being a pair of contrastive stress, will be used. They are: How many pets do you have? (a) I have two. (b) I study hard because I have to.

The sentence stress constraints determined to be relevant for this analysis are drawn from established constraints in OT studies of stress or adapted from examinations of stress from other perspectives:

● Culminativity: Each prosodic phrase (φ, ι) contains one and only one grid-mark (i.e., prominence or stress) (Ishihara, 2011:1881).

● Align R φ [Align (φ, R; P, R)]: For each φ, there is a P such that the right edge of φ coincides with the right edge of P (modeled after the template of Ishihara, 2011:1876.)

● *Unstressed content word at φ level: For each φ, the content words are allotted stress.

● *Unstressed new information: For each φ, words that produce new information are allotted stress.

● Max (stress)-assign one violation mark for every point of stress that exists in the phonological phrase level that is not stressed in the intonational phrase.

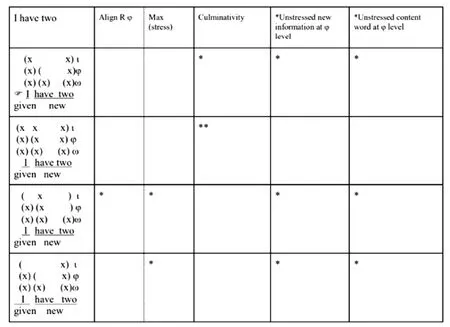

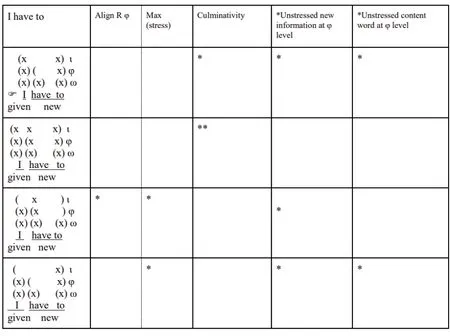

The actual sentence stress patterns varied from student to student, but there appears to be a rough pattern that is dependent on the level of English or length of English study. For example, beginners,such as students who did not major in English language and were freshmen, tended to put stress on every single word equally. Intermediate students, students who had studied college-level English courses and who generally had had more practice and exposure to listening and speaking in English,tended to assign stress only on some words but did not always do so on the right words. There were also advanced students whose sentence stress patterns approximated those produced by native speakers. As the most interesting of the three, the output of a representative intermediate student was chosen for the OT analysis:

How many pets do you have? I have two

I study hard because I have to.

The ranking order is as follows: Align R φ, Max (stress) >> Culminativity >> *Unstressed content word at φ level, *Unstressed new information.

This ranking order shows that the constraints that take into account information structure and category of words are low in consideration of the observed Chinese learners of English before any training.

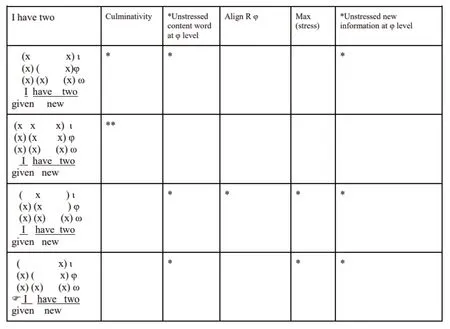

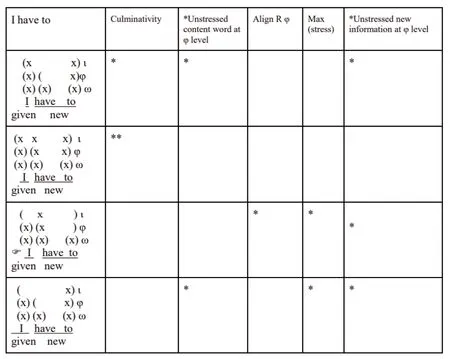

Below are some results showing the different constraint rankings and winners of the most common student response post-training course:

The new ranking order thus is as follows: Culminativity >> *Unstressed new information >> Align R φ >> Max (stress) >> *Unstressed content word at φ level

This ranking of a representative output of post-training results reveals how markedness constraints regarding content and information structure have altered.

This examination of a pair of phonologically similar sentences makes it more evident to notice the differences in the rankings of Chinese learners of English of different proficiency levels. By completing a period of study in the American accent training course, students were able to revise and update the ranking order of constraints in their interlanguage. The pair of test sentences make it clear that the promotion of the constraint, Culminativity, and the demotion of the constraints, Align R φ and Max(stress) are necessary for students to acquire L2 English stress patterns.

Conclusion

The results of this theoretical analysis reveal interesting insights concerning the empirical observation that for Chinese learners of English, L1 transfer in certain aspects of phonotactics appears to be harder to alter than that in sentence stress. This may be because the phonotactics of L1 has comparable complexity to L2, whereas, in the area of sentence stress, L1’s rules are nearly nonexistent.

The case of [da?n] to /da?/ serves as a fascinating exemplar of coalescence in the interlanguage of Chinese learners of English. However, it appears to be the tip of an iceberg, as many variations and related points of interest remain to be satisfactorily explained. The striking persistence of this particular“L1 transfer” effect is, in fact, much like the emergence of the unmarked. Its stability across students’experience levels and training times poses a classroom challenge and merits the development of future strategies specifically targeting coalescence.

Meanwhile, the initial patterns of sentence stress produced by the observed Chinese learners of English appear to be a correlation between the level of expertise or experience in English and the highest phonological level that was recognized. For example, beginner learners only noticed lexical stress and did not account for phonological phrase stress; intermediate learners showed variability in stress indicating recognition of phonological phrase stress, and advanced learners showed the most nuanced stress variability that could come from also being aware of intonational phrase stress (see Figure 2 below). The teaching of stress, then, entails not instructing any alternative system of stress but building up the incorporation of higher levels of phonological units.

Figure 2: Generalization of patterns of sentence stress at different proficiency levels

In the context of language teaching, phonotactic errors might be prominent to the instructor and tempting to be the focus of training through repetition, but some can be very difficult to change due to the order of the constraints of the interlanguage that makes a certain pronunciation very stable. The focus of pronunciation training might be better placed on sentence stress, which was observed to be an area of solid improvement. Errors in sentence stress may impede communication effectiveness more so than particular phonotactic errors.These observations may not only be of interest to instructors in China but also be relevant to those in English-speaking countries, for example, training programs at universities with a tradition of recruiting international graduate students as teaching assistants.

As a theoretical analysis of field observations, this paper also demonstrates the potential value of Optimality Theory as a tool for instructors of pronunciation seeking to identify areas in students’performance that may require targeting. As stressed previously, interlanguage may be idiosyncratic. In a classroom, students may have a variety of L1 dialect backgrounds and L2 proficiency levels; limited resources and time constraints may not permit instructors to systematically uncover all areas of each student’s errors. However, with OT, instructors may be able to logically deduce a student’s underlying ranking order of phonological constraints based on a sample of the student’s output and use this order to extrapolate and identify other potential issues. This may help instructors better tailor training to the needs of students. Although what has been discussed is drawn from the context of L1 Chinese and L2 English, the usefulness of this technique theoretically can be extended to other L1 and L2 combinations of interest worldwide, for example, L1 English and L2 Chinese.

Besides pedagogical implications, this paper, by explaining the variation in interlanguage levels of Chinese ESLs objectively in terms of linguistically grounded constraint rankings, may contribute to native English speakers’ clearer and less biased understanding of the pronunciation patterns of Chinese speakers of English in business and academic situations on the global stage. Popularizing such a perspective of interlanguage is conducive to the avoidance of misunderstandings of additional meanings conveyed by L1-influenced pronunciation and to the strengthening of successful international dialogue.

Contemporary Social Sciences2022年5期

Contemporary Social Sciences2022年5期

- Contemporary Social Sciences的其它文章

- Enlightenment from Development Experience of World-Class Universities in Foreign Inland Regions

- A Study of Sanxingdui Museum’s Building of International Communication Capacity

- On the Development of Modern Tourism in Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan Province

- Research on the Development of Rural Tourism in the Context of Comprehensively Promoting Rural Revitalization: A Social-System-Based Approach

- Rural Road Investment and Economic Growth

- Research on the Influence Degree and Effect of Support on Innovation Incentives for R&D Personnel in Micro and Small Enterprises: An Empirical Study based on the China Micro and Small Enterprise Survey (CMES)