Mobility and social deprivation on primary care utilisation among paediatric patients with asthma

Jennifer A Lucas , Miguel Marino, Sophia Giebultowicz, Katie Fankhauser, Shakira F Suglia, Steffani R Bailey, Andrew Bazemore, John Heintzman,

1Department of Family Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon, USA

2OCHIN Inc, Portland, Oregon, USA

3Department of Epidemiology, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, USA

4American Board of Family Medicine, Lexington, Kentucky, USA

5Center for Professionalism & Value in Health Care, Washington, DC, USA

ABSTRACT Objective Asthma care is negatively impacted by neighbourhood social and environmental factors, and moving is associated with undesirable asthma outcomes. However, little is known about how movement into and living in areas of high deprivation relate to primary care use. We examined associations between neighbourhood characteristics, mobility and primary care utilisation of children with asthma to explore the relevance of these social factors in a primary care setting.Design In this cohort study, we conducted negative binomial regression to examine the rates of primary care visits and annual influenza vaccination and logistic regression to study receipt of pneumococcal vaccination. All models were adjusted for patient- level covariates.Setting We used data from community health centres in 15 OCHIN states.Participants The sample included 23 773 children with asthma aged 3–17 across neighbourhoods with different levels of social deprivation from 2012 to 2017. We conducted negative binomial regression to examine the rates of primary care visits and annual influenza vaccination and logistic regression to study receipt of pneumococcal vaccination. All models were adjusted for patient- level covariates.Results Clinic visit rates were higher among children living in or moving to areas with higher deprivation than those living in areas with low deprivation (rate ratio (RR) 1.09, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.17; RR 1.05, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.11). Children moving across neighbourhoods with similarly high levels of deprivation had increased RRs of influenza vaccination (RR 1.13, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.23) than those who moved but stayed in neighbourhoods of low deprivation.Conclusions Movement into and living within areas of high deprivation is associated with more primary care use, and presumably greater opportunity to reduce undesirable asthma outcomes. These results highlight the need to attend to patient movement in primary care visits, and increase neighbourhood- targeted population management to improve equity and care for children with asthma.

INTRODUCTION

There is consistent and compelling evidence that neighbourhood characteristics affect paediatric asthma outcomes. Asthma is influenced by factors related to the physical environment (air quality, built environment), social position in the neighbourhood (race/ethnicity, immigration status) and other social environmental factors, such as those relating to neighbourhood deprivation, wealth and inequality.1–6Research has shown that living in or moving into an impoverished neighbourhood is associated with higher risk of asthma when compared with never having lived in a poor neighbourhood.7

More frequent changes in neighbourhood may also influence asthma outcomes or asthma care utilisation. A Welsh team, using data from more than 200 000 children, found that moving within the first year of life was associated with increased risk of future emergency hospitalisation for asthma.8Other studies from Europe and New Zealand have also found residential mobility to be associated with negative health outcomes910possibly because moves can be an indication of financial insecurity or other underlying family instability.

According to the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program’s Expert Panel, one of the main goals in asthma care is asthma control, which includes reducing impairment (symptoms) and reducing risk (eg, preventing exacerbations and reducing emergency care).11Primary care clinics are essential in this endeavour, because they are where many asthma management medications are prescribed and asthma action plans are developed. Primary care clinics are also increasingly screening for a wide range of socioeconomic adversity indicators, yet screening is labour intensive and therefore often not feasible in busy clinical environments.12–14An alternative could be to use administrative data on address changes and zip- code linked neighbourhood- level deprivation data to identify clinical populations at risk for negative outcomes. If this risk stratification is meaningful, it could help prioritise care for populations with greater needs without necessitating large- scale patient- facing screening. Address data are readily accessible by many clinics, and could be used to therefore better assess risk. However, these associations between neighbourhood- level deprivation, moving neighbourhoods and primary care utilisation in children with asthma has not been studied at a national level in the USA, though some work has studied neighbourhood- level deprivation on a smaller scale.1516

Community health centres (CHCs) are clinics in the USA that provide primary care to anyone regardless of insurance status or the patient’s ability to pay for care in a defined community. They serve disproportionately high numbers of low- income patients, including residents of public housing and those experiencing homelessness.17These features make CHCs particularly appropriate settings in which to examine how residential mobility across neighbourhoods with varying levels of social deprivation affects routine primary care utilisation (regular visits and immunisations) in children with asthma. We hypothesised that children with asthma who receive care in CHCs would have higher care needs and therefore higher primary care utilisation if they (1) moved from areas with little deprivation to areas with more deprivation and (2) had higher number of residential moves within areas of high deprivation.

METHODS

Data and inclusion criteria

Our analysis uses OCHIN (formerly Oregon Community Health Information Network until other states joined) data on children with asthma from 15 states, aged 3–17 who had ≥1 ambulatory visit in study clinics between 1 January 2012 and 31 December 2017 and had documented geocoded addresses. Guidelines encourage regular clinical contact in children with asthma, and it is especially important to vaccinate children with asthma for other respiratory illnesses.11Study participant flow based on inclusion criteria is reported in online supplemental figure 1.

Outcomes

We chose the outcomes of office visits and immunisations because they apply to all children with asthma regardless of asthma severity or current symptoms. Specifically, the outcome variables were (1) rate of primary care visits (the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel recommends that children with asthma be seen twice/year at minimum11); (2) annual rate of influenza immunisation, as children who have asthma are also at an increased risk of complications from influenza, which may require hospitalisation,18–20and (3) a binary indicator of whether the child had received ≥1 pneumococcal vaccination, as the pneumococcal immunisation is recommended for children with asthma, who may be more at risk for invasive pneumococcal disease.21Asthma diagnosis was determined by having ≥1 International Classification of Disease (ICD)-9 codes of 493* or ICD-10 codes of J45* documented at an visit during the study period. We identified influenza and pneumococcal immunisations using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s National Center of Immunization and Respiratory Diseases vaccine administered codes,22which were reviewed and cleaned by analysts, and reviewed again for final categorisation by a practicing clinician.

Independent variables

The main independent variable was a categorical indicator of residential mobility during the study period with five groups: (1) all moves within high deprivation neighbourhoods (‘a(chǎn)lways high’); (2) all moves within low deprivation neighbourhoods (‘a(chǎn)lways low’); (3) a move from a highly deprived neighbourhood to one with low deprivation (‘high to low’); (4) a move from a neighbourhood with low deprivation to one with high deprivation (‘low to- high’) and (5) multiple moves (>2 moves) across neighbourhoods with at least one differing deprivation level (‘varied’). Children who did not move at all either fell into the always high deprivation group or always low deprivation group. Addresses were obtained from the electronic health record (EHR); these are collected as a matter of routine care. The current address recorded in the EHR is a reliable measure of exposure to neighbourhood level deprivation.23To measure social deprivation in an area, we used the Social Deprivation Index (SDI) of the census tract in which the patient resided at the time. The SDI is a validated composite measure of neighbourhood- level social determinants including income, employment, education, housing and transportation, and can be used to represent the overall socioeconomic conditions in a geographical area.24The index was created by the Robert Graham Center for the year 2015, using a subset of 2011–2015 American Community Survey 5- year estimates.2425The SDI score (a unitless range of 0–100) was split at the median (based on this sample, median=83) to create the ‘low deprivation’ and ‘high deprivation’ categories. Low deprivation included values between 0 and 83, high deprivation included values between 83 and 100. The models also include the number of moves experienced by each child (categorised as 0, 1–2, and ≥3 moves).26

Patient- level characteristics added as covariates included: age at first visit (categorised in years as 3–5, 6–11, 12–17), sex (female or male), categorical indicator of rate of visits per year in the models analysing vaccination (<1, 1–2, 3–4, ≥5), primary insurance type during the study period recorded at each visit (never insured, some private insurance, some public insurance, some public and private insurance), income as percent of US federal poverty level (FPL), and race/ethnicity (Latinx, non- Hispanic white, non- Hispanic black). While we generally use ‘Latino/a/x’ because it can be preferred in populations similar to our study population, the actual ethnicity information collected by clinics is ‘Hispanic’ and ‘non- Hispanic white’. We also included body mass index (BMI) over time, as asthma severity and control may be influenced by obesity.2728BMI was calculated from EHR data from clinic visits and categorised as never overweight/obese, overweight/obese at some clinic visits, or overweight/obese at every clinic visit during the study period. Overweight was defined as having a BMI ≥85th percentile to <95th percentile for one’s respective age and sex, while obesity was defined as a BMI ≥95thpercentile, consistent with CDC standards.29BMI and BMI percentile were calculated at the visit level using the R package childsds.30

Statistical analysis

We conducted descriptive analyses to examine patient characteristics. For the analyses evaluating the rates of visits and influenza immunisations, we used generalised estimating equations (GEE) negative binomial regression models as a function of social deprivation mobility groups, adjusted for all of the above- listed covariates. Negative binomial modelling was used instead of a GEE Poisson model due to its flexibility to account for overdispersion of outcome data. Models were fitted with a compound symmetry correlation structure and empirical sandwich variance estimator to obtain adjusted rate ratios (RRs) and their corresponding 95% CIs, accounting for clustering of patients within CHCs. For the analyses evaluating the odds of ever having had a pneumococcal vaccination (past age 2), we used GEE logistic regression models to estimate adjusted ORs, also while accounting for clustering of patients by CHC.

As a sensitivity analysis, we examined the above outcomes in subsamples stratified by number of moves (0, 1–2, or ≥3 moves), as we expected that those with higher residential mobility might have differing patterns of primary care utilisation. We also stratified by race/ethnicity as children in different racial/ethnic groups may use health services at different rates. R and Stata software were used to perform statistical analysis. Two- sided statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

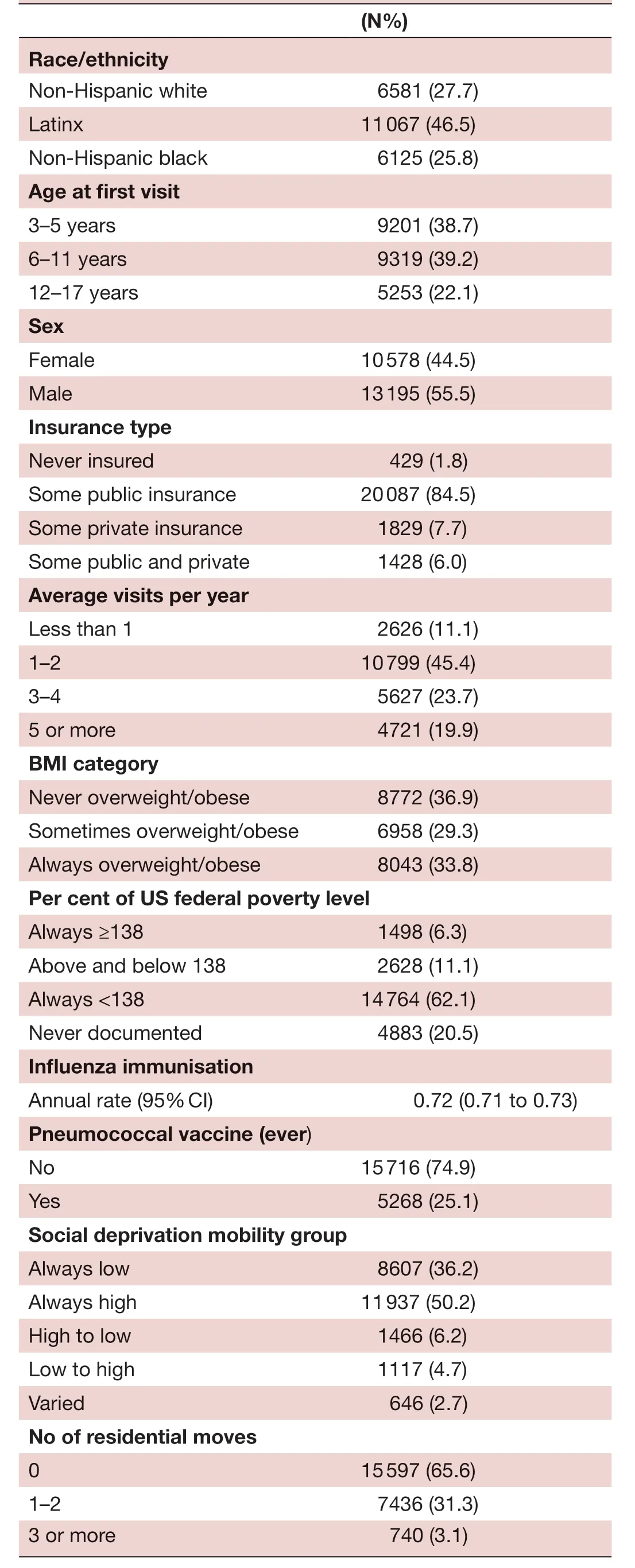

The sample was composed of 23 773 children with asthma who received primary care in CHCs. Table 1 shows patient characteristics. The sample included Latinx (46.5%), non- Hispanic white (27.7%), and non- Hispanic black (25.8%) children. Slightly more than half the population was male (55.5%) and many patients first visit in the study period was at age 3–5 years (38.7%) or age 6–11 years (39.2%). Most patients had some public insurance (84.5%) and 1–2 ambulatory visits per year (45.4%). In this sample, 33.8% of patients were overweight/obese at every visit and 36.9% were never overweight/obese. The majority of children (62.1%) lived in a household reporting income <138% FPL at every ambulatory visit. The annual rate of influenza vaccination was 0.72 vaccines per year, and 25.1% had received a pneumococcal vaccination within the study period. The majority of children had 0 residential moves within the study period (65.6%), while 31.3% had 1–2 residential moves within the study period. The largest proportion of patients were in the always high (50.2%) or always low (36.2%) deprivation mobility groups. 6.2% of children were in the high- to- low deprivation group, and 4.7% were in the low- to- high group (table 1).

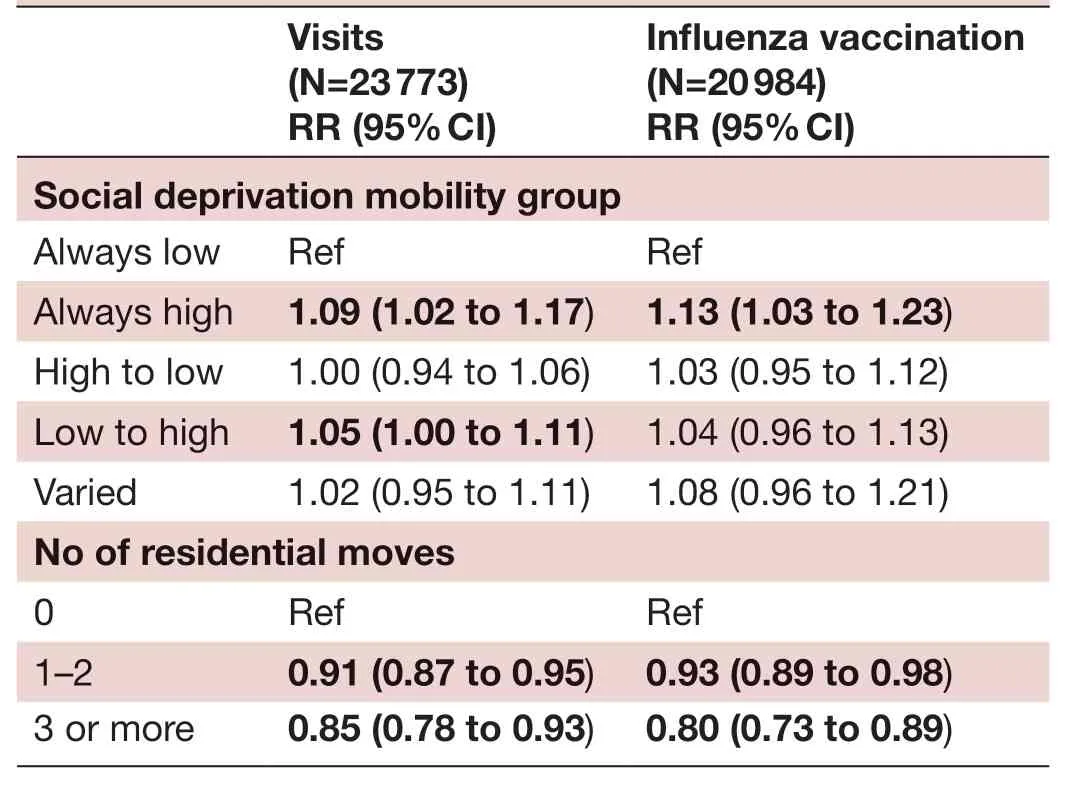

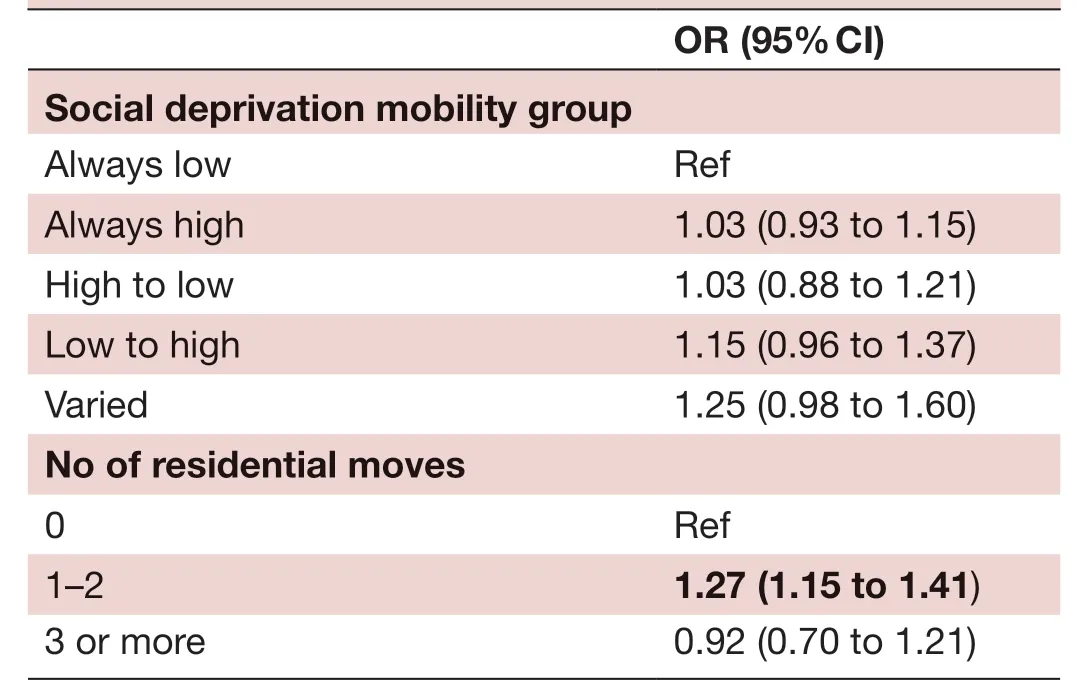

Children living in the always high deprivation group and in the low- to- high deprivation group had higher adjusted RRs of clinical visits than those in the always low group (RR 1.09, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.17 and RR 1.05, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.11, respectively) (table 2). The annual influenza immunisation rate was also higher in the always high deprivation group (RR 1.13, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.23) compared with the always low group (table 2). Similar ORs of pneumococcal vaccination were seen between all groups (table 3). Full model results are reported in online supplemental tables 1 and 2.

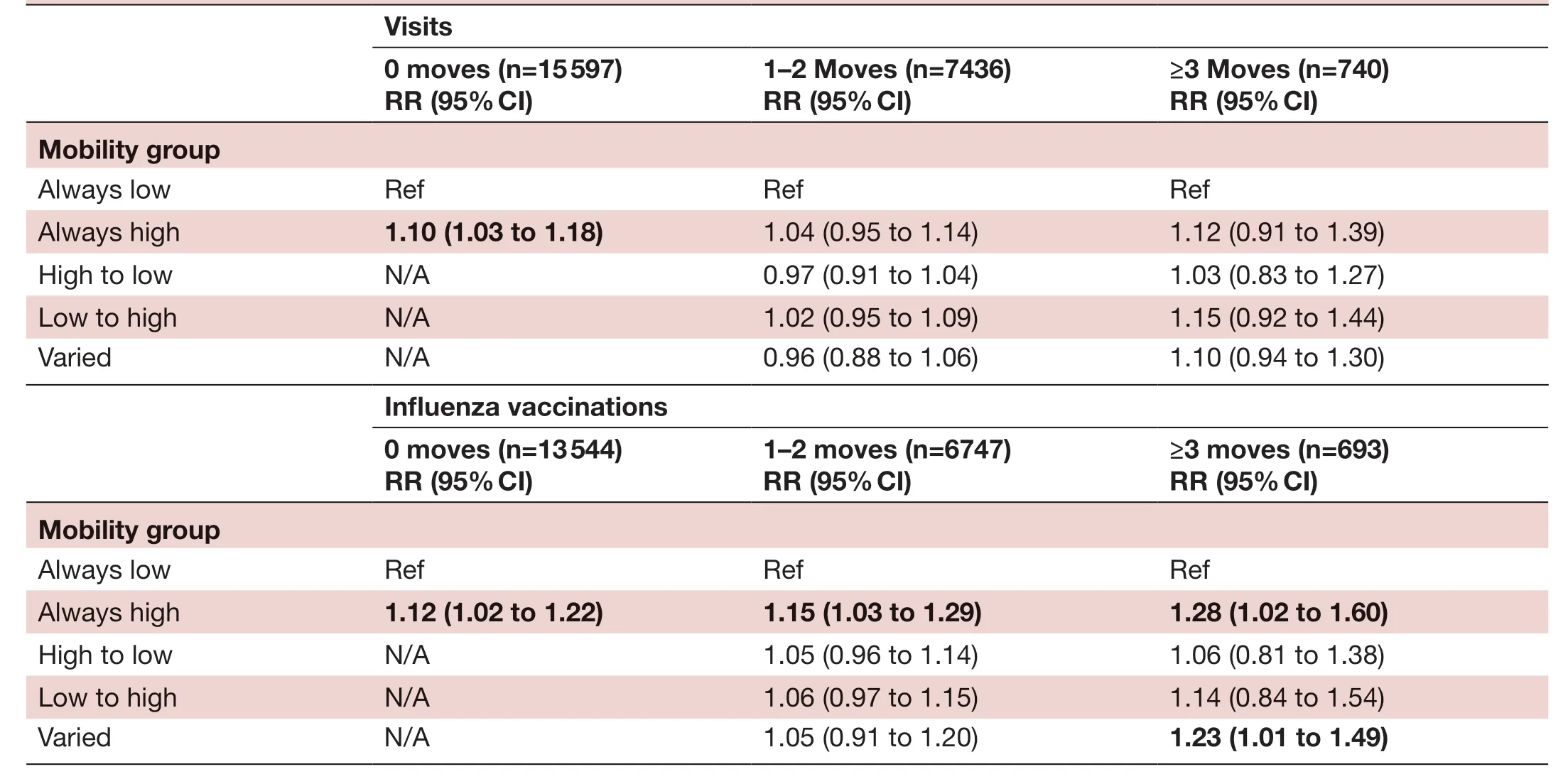

Sensitivity analysis: stratified by number of residential moves

Children with no recorded residential moves who lived in the always high SDI areas had increased RRs of visits compared with children with no recorded moves living in the always low areas (table 4). All other SDI mobility groups had similar RRs of visits, regardless of whether they had 1–2 residential moves or ≥3 residential moves within the study period.

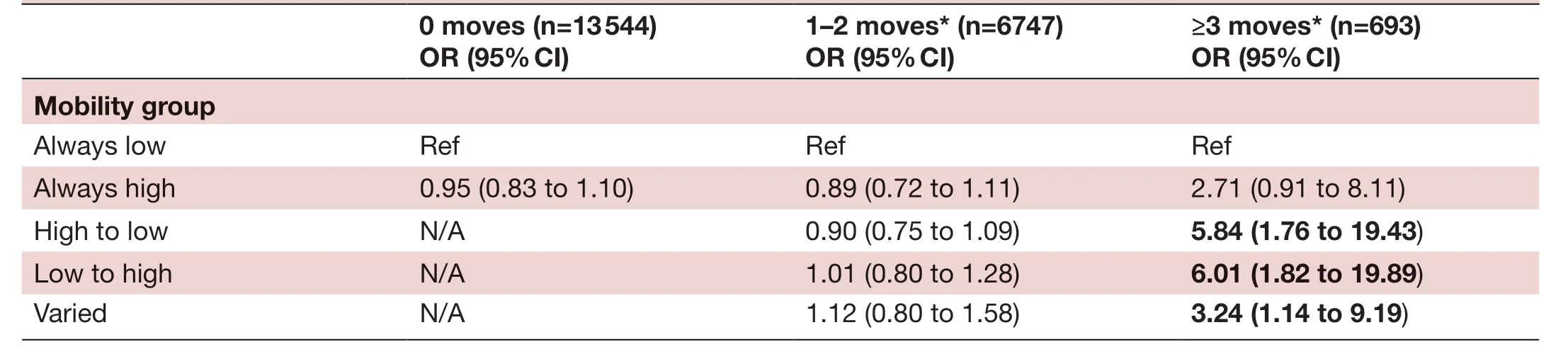

Influenza vaccine rates were higher in children with no moves in the always high group compared with the always low group. Influenza vaccine rates were also higher in the always high group compared with the always low group in those with 1–2 moves, and in the always high and varied groups compared with the reference group for children with ≥3 moves (table 4). Odds of pneumococcal vaccination were increased among those with ≥3 moves in the high- to- low, low- to- high, and varied groups compared with those in the always low reference category (table 5). We acknowledge the large confidence intervals due to small sample size in table 5, and interpret these results with caution.

TabIe 1 Patient characteristics overall and in children with asthma (N=23 773)

TabIe 2 Rate ratios of visits and influenza vaccinations

TabIe 3 ORs of pneumococcal vaccination ever (within study period) (N=20 984)

DISCUSSION

This study used EHR data from a multistate network of clinics linked with administrative and location data to examine the effects of social deprivation and residential mobility on three indicators of routine primary care utilisation in a CHC cohort of children with asthma, preschool age and older. In an era of increasing attention to and collection of place- based social determinants of health data, it is crucial to know how neighbourhood features and residential mobility are associated with healthcare utilisation.

TabIe 4 Rate ratios (RRs) of visits and influenza vaccinations, stratified by number of residential moves

We found three significant associations worthy of further discussion. First, living or moving within/to a high social deprivation area was associated with increased utilisation of primary care and rates of influenza vaccination. This overarching pattern was supported by significant associations in the whole study population (living within or moving to a high deprivation area), as well as positive findings in the stratified analysis (higher likelihood of visits in the children with no moves in a high deprivation neighbourhood and a higher influenza vaccine rate across all move strata in high deprivation neighbourhoods.) That children with asthma in deprived neighbourhoods appear to use more primary care has several important implications. It may imply worse control of this chronic disease (though we did not limit these visits to asthma visits), or that they have increased healthcare needs in general. But while neighbourhood deprivation may signal providers and clinics that children may use more care (and require more proactive disease or health management), it also implies that CHCs may be an important point of contact for these children. Rather than less interaction with these centres, children from deprived neighbourhoods have more interaction with primary care than their less deprived peers, and CHCs could be viewed as valuable platforms for social and health interventions in these communities.

TabIe 5 ORs of pneumococcal vaccination ever (within the study period) stratified by number of residential moves

Second, moving was associated with less visits and influenza vaccination than those children who did not move. Residential mobility, in a low- income population like that which is served by CHCs, has been shown to cause disruptions in health and healthcare.8–10In this analysis, we also find evidence that such mobility is also associated with reduced routine care utilisation in children with a chronic disease. From these findings we are unable to determine if these children received sufficient or quality care, but the fact that they use less than their counterparts raises concern that this is possible, and clinical organisations and future research could consider further evaluating risk screening strategies that employ number of address changes from administrative data in order to stratify clinical risk.

Thirdly, more moves were associated with higher rates of receiving pneumococcal vaccination, as evidenced by an increased frequency of this immunisation in the whole sample with 1–2 moves, and in the stratified sample with 3+ moves across multiple neighbourhood types. While pneumococcal vaccination in our age strata of children with asthma may be routine, it may be more common in children who did not complete the entire pneumococcal series earlier than age three, or if they have had particularly severe symptoms requiring oral steroids.3132While we could not determine these specific factors from our data, the elevated odds of this immunisation in children with more moves does suggest disruptions to the completion of routine preventive measures. This lends further support to the idea that number of moves may be considered for future study as a risk stratification method.

This study had several limitations. All children received care at CHCs, therefore our findings may not be generalisable outside of this setting. While our data did include many clinical factors, we did not have any data on patient beliefs and perceptions regarding vaccination, important factors to consider when examining vaccination rates. It is also possible that children could have moved out of the CHC network, thus our rates may be underestimated. However, research in CHCs suggests that patients often do not leave their networks.33Our data also did not have information on the reason for the move.

CONCLUSIONS

This analysis of the neighbourhood deprivation and residential mobility of children with asthma seeking care at CHCs demonstrated increased utilisation of primary care visits and influenza vaccinations in children in or who moved to high social deprivation neighbourhoods, and reduced utilisation of these services in children who changed addresses. Researchers and healthcare organisations should consider the opportunity for health and social interventions and care that this utilisation may provide. They should also consider further study of the incorporation of assessing residential mobility into clinical risk prediction in this cohort of children.

AcknowledgementsThe authors would like to acknowledge Laura Gottlieb, MD, MPH, who provided valuable commentary and insight to this paper. This work was conducted with the Accelerating Data Value Across a National Community Health Centre Network (ADVANCE) Clinical Research Network (CRN). The ADVANCE network is led by OCHIN in partnership with Health Choice Network, Fenway Health, Oregon Health and Science University and the Robert Graham Centre HealthLandscape.

ContributorsJAL and MM conceptualised and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, supervised data collection, analysed the data and reviewed and revised the manuscript. JH conceptualised and designed the study, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. KF created the analytic dataset, contributed to the analytic design, helped interpret findings and reviewed and revised the manuscript. SFS, SRB and AB helped interpret findings, and reviewed and revised the manuscript, SG collected and cleaned data, contributed to the analytic design, helped interpret findings, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FundingADVANCE is funded through the Patient Centred Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), contract number RI- CRN-2020–001. This work was supported by an NIH National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities grant (R01MD011404; BACKGROUND Study, PI: John Heintzman).

Competing interestsNone declared.

Patient consent for publicationNot required.

Ethics approvalThe Institutional Review Board at Oregon Health & Science University approved this study: STUDY00017724: Bettering Asthma Care in Kids- Geographic Social Determinants Data to Understand Disparities.

Provenance and peer reviewNot commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statementData may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. Data are a limited (partially deidentified) dataset from electronic health records. Data are available to investigators for a fee for those who are willing and able to partner with OCHIN on their analysis.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer- reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Open accessThis is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY- NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non- commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non- commercial. See: http:// creativecommons. org/ licenses/ by- nc/ 4. 0/.

ORCID iD

Jennifer A Lucas http:// orcid. org/ 0000- 0002- 2895- 9809

Family Medicine and Community Health2021年3期

Family Medicine and Community Health2021年3期

- Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- Trends in the prevalence and incidence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in Iran: findings from KERCADRS

- Sexually transmitted infection laboratory testing and education trends in US outpatient physician offices, 2009–2016

- Setting up an epidemiological surveillance system for vaccine hesitancy outbreaks and illustration of its steps of investigation

- Mastering stakeholders’ engagement to reach national scale, sustainability and wide adoption of digital health initiatives: lessons learnt from Burkina Faso

- Insights into the design, development and implementation of a novel digital health tool for skilled birth attendants to support quality maternity care in Kenya

- Impact evaluation of immunisation service integration to nutrition programmes and paediatric outpatient departments of primary healthcare centres in Rumbek East and Rumbek Centre counties of South Sudan