Cytapheresis re-induces high-rate steroid-free remission in patients with steroid-dependent and steroidrefractory ulcerative colitis

Masahiro Iizuka, Takeshi Etou, Yosuke Shimodaira, Takashi Hatakeyama, Shiho Sagara

Abstract

BACKGROUND It is a crucial issue for patients with refractory ulcerative colitis (UC), including steroid-dependent and steroid-refractory patients, to achieve and maintain steroid-free remission. However, clinical studies focused on the achievement of steroid-free remission in refractory UC patients are insufficient. Cytapheresis(CAP) is a non-pharmacological extracorporeal therapy that is effective for active UC with fewer adverse effects. This study comprised UC patients treated with CAP and suggested the efficacy of CAP for refractory UC patients.

AIM To clarify the efficacy of CAP in achieving steroid-free remission in refractory UC patients.

METHODS We retrospectively reviewed the collected data from 55 patients with refractory UC treated with CAP. We analyzed the following points: (1 ) Efficacy of the first course of CAP; (2 ) Efficacy of the second, third, and fourth courses of CAP in patients who experienced relapses during the observation period; (3 ) Efficacy of CAP in colonic mucosa; and (4 ) Long-term efficacy of CAP. Clinical efficacy was evaluated using Lichtiger’s clinical activity index or Sutherland index (disease activity index). Mucosal healing was evaluated using Mayo endoscopic subscore.Written or oral informed consent was obtained from patients and/or parents of patients aged younger than 20 years.The primary and secondary endpoints were the rate of achievement of steroidfree remission and the rate of sustained steroid-free remission, respectively.Statistical analysis was performed using the paired t-test and chi-squared test.

RESULTS The rates of clinical remission, steroid-free remission, and poor effectiveness after CAP were 69 .1 %, 45 .5 %, and 30 .9 %, respectively. There were no significant differences in rate of steroid-free remission between patients with steroiddependent and steroid-refractory UC. The mean disease activity index and Lichtiger’s clinical activity index scores were significantly decreased after CAP (P< 0 .0001 ). The rates of steroid-free remission after the second, third, and fourth courses of CAP in patients who achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP were 83 .3 %, 83 .3 %, and 60 %, respectively. Mucosal healing was observed in all patients who achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP. The rates of sustained steroid-free remission were 68 .0 %, 60 .0 %, and 56 .0 % at 12 , 24 , and 36 mo after the CAP. Nine patients (36 %) had maintained steroid-free remission throughout the observation period.

CONCLUSION Our results suggest that CAP effectively induces and maintains steroid-free remission in refractory UC and re-induces steroid-free remission in patients achieving steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP.

Conflict-of-interest statement: We declare no conflict-of-interest associated with this manuscript.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4 .0 )license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially,and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: htt p://creativecommons.org/License s/by-nc/4 .0 /

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification Grade A (Excellent): 0 Grade B (Very good): 0 Grade C (Good): C, C, C Grade D (Fair): 0 Grade E (Poor): 0

Received: November 4 , 2020

Peer-review started: November 4 ,2020

First decision: January 23 , 2021

Revised: February 11 , 2021

Key Words: Ulcerative colitis; Cytapheresis; Steroid-dependent; Steroid-refractory;Steroid-free remission; Inflammatory bowel disease

INTRODUCTION

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) of unknown etiology, which can affect the entire colon. Several treatments for UC are available to induce and maintain the clinical remission of the disease. Among these treatments,corticosteroids (CSs) were first introduced by Truelove and Witts[1]and currently remain the first-line treatment to induce remission in moderate to severe UC patients.Faubion et al[2] reported that 34 % of UC patients were treated with CSs and that immediate outcomes were complete remission in 54 %, partial remission in 30 %, and no response in 16 % of patients. They also showed that 1 -year outcomes were prolonged response in 49 %, CS dependence in 22 %, and operation in 29 % of patients[2]. Despite the effectiveness of CSs in inducing clinical remission in UC patients, it has been reported that 16 %-18 % of patients had no response to steroids(steroid-refractory), and the rate of steroid dependence was 17 %-22 % at 1 year following treatment with the initial CS therapy and increased to 38 % mostly within 2 years[2-7].

Refractory UC generally includes both steroid-dependent and steroid-refractory UC.Along with the recent advancements of the treatment for UC, several breakthrough treatments, including biologics, have been developed for refractory UC[8-23]. A metaanalysis showed that anti-tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) antibodies had more clinical benefits than placebo control as evidenced by the former’s increased frequency of clinical remission, steroid-free remission, endoscopic remission, and decreased frequency of colectomy[24]. It was also reported that the rates of induction of steroidfree remission in refractory UC patients with anti-TNF-α antibodies ranged from 40 .0 % to 76 .5 %[6 ,9 ,11 ,15 ,16 ,18]. However, studies that analyzed the efficacy of biologics focused on the achievement of steroid-free remission in refractory UC patients are insufficient. On the contrary, despite the efficacy of anti-TNF-α antibody for UC,secondary loss of response (LOR) is a common clinical problem with its incidence rate ranging from 23 % to 46 % at 12 mo after anti-TNF-α initiation[25]. Moreover, it was reported that the incidence rates of LOR were 58 .3 % (adalimumab) and 59 .1 %(infliximab) during maintenance therapy (mean follow-up: 139 wk and 158 .8 wk,respectively)[26]. Regarding vedolizumab, it was also reported that the cumulative rate for LOR in UC patients was 39 % at 12 mo[27]. Concerning the adverse events of biologics, similar with other biological therapies, anti-TNF-α therapy may lead to serious infection, demyelinating disease, and associated mortality[28]. It was also reported that the use of anti-TNF-α antibody combined with thiopurines was associated with an increased risk of lymphoma in IBD[29].

Thiopurines have been conventionally used for the treatment of steroid-dependent UC[30 -35]. Two randomized controlled trials have shown that the rates of the induction of CS-free remission with thiopurines in steroid-dependent UC patients were 44 % and 53 %, respectively[34 ,35 ]. However, Jharap et al[32]reported that thiopurine therapy has failed in approximately one-quarter of IBD patients within 3 mo after treatment initiation, which is mostly due to drug intolerance or toxicity. Moreover, thiopurines are associated with potential serious adverse events, such as an increased risk of lymphoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer[33].

Cytapheresis (CAP) is a non-pharmacological extracorporeal therapy and has been developed as a treatment for UC[36 -42]. CAP is performed using two methods, namely,granulocyte and monocyte adsorptive apheresis (GMA), which uses cellulose acetate beads (Adacolumn, JIMRO Co., Ltd., Gunma, Japan), and leukocytapheresis (LCAP),which uses polyethylene phthalate fibers (Cellsorba., Asahi Kasei Medical Co., Ltd.,Tokyo, Japan)[42 ,43]. GMA selectively depletes elevated granulocytes and monocytes from the patients’ circulation, but spares most of the lymphocytes[42]. LCAP exerts antiinflammatory effects by removing activated leukocytes or platelets from the peripheral blood through an extracorporeal circulation[43]. It has been shown that CAP is an effective therapeutic strategy for patients with active UC with fewer adverse effects[36 -42]. However, to date, the number of studies focused on the efficacy of CAP in both steroid-dependent and steroid-refractory UC has been limited[43 -54].

Despite the excellent therapeutic effects of CS for UC patients, prolonged CS therapy can result in multiple serious side effects such as diabetes mellitus, infection,osteonecrosis, and steroid-associated osteoporosis[55 ]. Furthermore, McCurdy et al[56]showed that IBD patients receiving CSs and immunomodulators were more likely to be diagnosed with cytomegalovirus diseases than IBD patients not receiving CSs and immunomodulators. Therefore, management of refractory UC patients is a crucial issue, and the goal of the treatment for such patients should be steroid-free remission.However, as described above, clinical studies focused on the achievement of steroidfree remission in refractory UC patients are insufficient. We had treated many UC patients with CAP and consequently suggested the efficacy of CAP for refractory UC patients. Considering these backgrounds, we retrospectively analyzed the efficacy of CAP specifically focused on the achievement of steroid-free remission in patients with steroid-dependent and steroid-refractory UC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

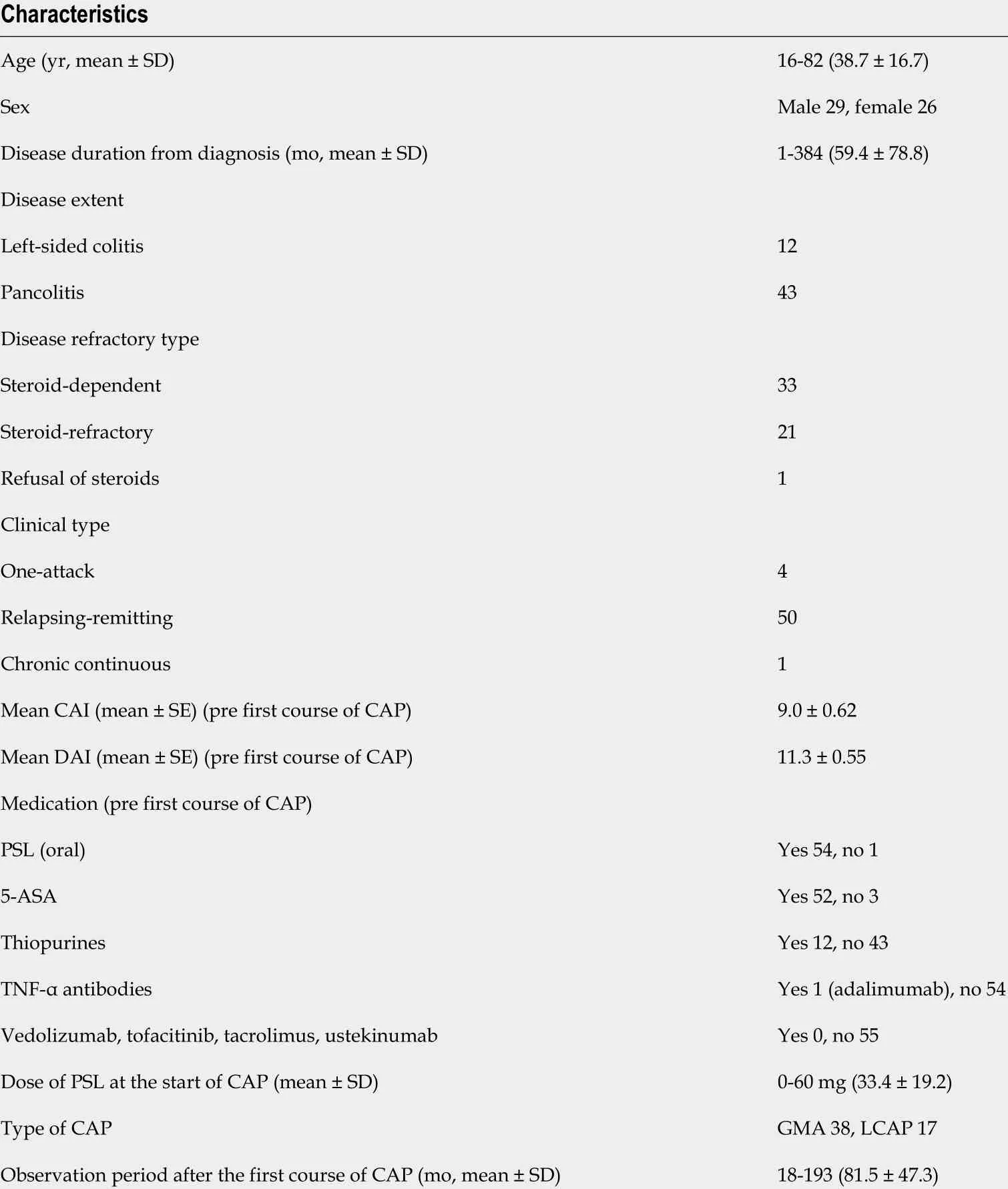

Patients

We retrospectively reviewed the collected data from 55 (male 29 , female 26 ) patients aged 16 -82 years (mean ± SD, 38 .7 ± 16 .7 years) with active refractory UC (steroiddependent type 33 , steroid-refractory type 21 , refractory but refused steroid therapy 1 )treated with CAP (GMA 38 , LCAP 17 ) between September 2002 and December 2019 (Table 1 ). The detailed clinical profiles of the patients enrolled in this study are shownin Table 1 . The dosage of prednisolone and the concomitant therapies at apheresis commencement are also shown in Table 1 . The rates of concomitant use of prednisolone, 5 -aminosalicylic acid, and immunomodulators were 98 .2 % (54 /55 ),94 .5 % (52 /55 ), and 21 .8 % (12 /55 ), respectively. Anti-TNF-α antibody (adalimumab)was administered to one patient. In most patients, concomitant medications except prednisolone were continued at the same dosage. The dosage of prednisolone was tapered or discontinued according to patients’ clinical improvement during the CAP therapy.

Table 1 Patients’ characteristics in this study

This retrospective study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Akita Red Cross Hospital (approval No: 195 ) and Akita University School of Medicine (approval No:2419 ). Written or oral informed consent was obtained from patients and/or parents of patients aged younger than 20 years.

The primary endpoint of this study was the rate of achievement of steroid-free remission in refractory UC patients after the CAP therapy. The achievement of steroidfree remission included the induction of steroid-free remission in the first course of CAP and re-induction of steroid-free remission in the second, third, and fourth courses of CAP. The secondary endpoint was the rate of sustained steroid-free remission in refractory UC patients after the CAP therapy.

Definition of steroid-dependent and steroid-refractory UC

Steroid-dependent UC was defined as the disease that initially responds to steroids but could not maintain control of symptoms without steroids and requires low doses of steroids to remain symptom-free[6, 57]. Steroid-refractory UC was also defined as active UC characterized by the failure to respond to 0 .75 -1 .5 mg/kg per day of prednisolone administered over at least 1 wk[43 ,57].

CAP

Each patient was treated with 5 to 20 GMA or LCAP sessions (mean ± SD, 8 .8 ± 3 .8 sessions). A total of 20 patients were treated with 5 sessions of CAP, 29 patients with 10 sessions, 1 patient with 9 sessions, 1 patient with 15 sessions, 1 patient with 18 sessions, and 3 patients with 20 sessions. Under the Japanese health insurance treatment system, the 11 th CAP session was performed at 1 mo after the 10thCAP session in patients who received more than 10 CAP sessions. CAP was performed once weekly in principle. However, in some patients with severe UC, CAP was exceptionally performed twice a week for the first 2 -3 wk (intensive CAP). CAP was also exceptionally performed once 2 wk for the last several weeks in some patients whose symptoms improved to mild after the treatment with several sessions of CAP.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with serious cardiac, kidney, or liver diseases; malignancy; coagulation disorders; infections; history of hypersensitivity to heparin; severe dehydration,granulocytopenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia; and patients taking angiotensinconverting enzyme inhibitor were excluded.

Evaluation of the efficacy of CAP

Efficacy of the first course of CAP:Clinical efficacy between April 2008 and December 2019 were evaluated using the Lichtiger’s clinical activity index (CAI)[58]and that between September 2002 and March 2008 was evaluated using Sutherland index(disease activity index, DAI)[59]. Clinical remission was defined as decreased Lichtiger’s CAI in 4 or less or decreased DAI in less than 2 .5 [60]. In this study, we assessed patients who did not achieve clinical remission after CAP, suggesting the “poor effectiveness of CAP”. We evaluated the efficacy of CAP approximately 4 wk after the last apheresis session. We also examined the rate of steroid-free remission. We have defined“steroid-free” as the point when both oral steroids and enemas including steroids were discontinued. However, suppositories including small amounts of steroids were permitted, as an exception.

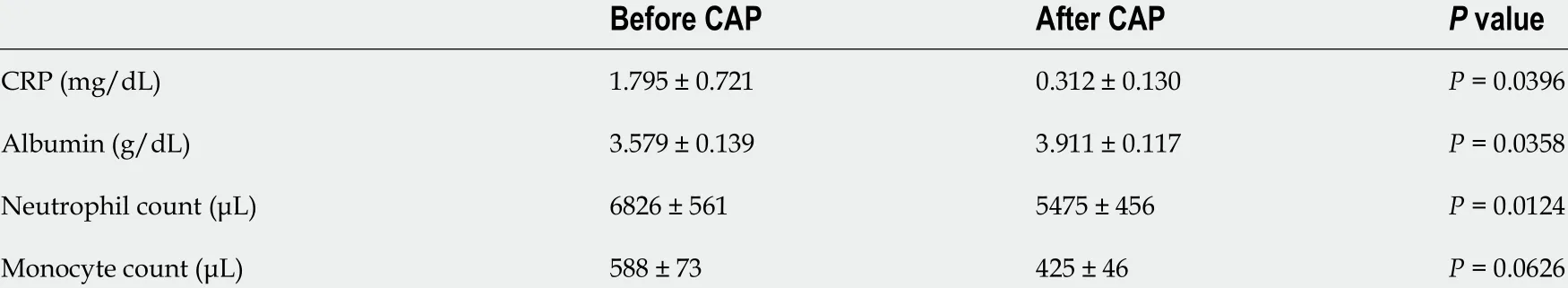

Laboratory data (C-reactive protein level, serum albumin concentration, neutrophil count, and monocyte count) before and after CAP were also examined in 28 patients treated between April 2008 and December 2019 .

Efficacy of the second, third, and fourth courses of CAP:Efficacy of the second course of CAP in patients experiencing a relapse during the observation period was assessed. Furthermore, efficacy of the third and fourth courses of CAP was also assessed specifically in patients who achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP and experienced relapses during the observation period.

Efficacy of CAP in colonic mucosal inflammation:Endoscopic findings after the first course of CAP in patients who achieved steroid-free remission were evaluated using the Mayo endoscopic subscore[61 ]. A score ≤ 1 suggested mucosal healing.

Long-term efficacy:Long-term efficacy of CAP in patients who achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP was examined by assessing (1 ) the rate of sustained steroid-free remission at 12 , 24 , and 36 mo after the first course of CAP and(2 ) overall rate of maintaining sustained steroid-free remission throughout the observation period.

The surgical operation rate:The surgical operation rates of the patients within 6 mo, 3 years, and throughout the observation period after the first course of CAP were examined.

Statistical analysis:Statistical analysis was performed using the paired t-test, and chisquared test, and a P value < 0 .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Efficacy of the first course of CAP

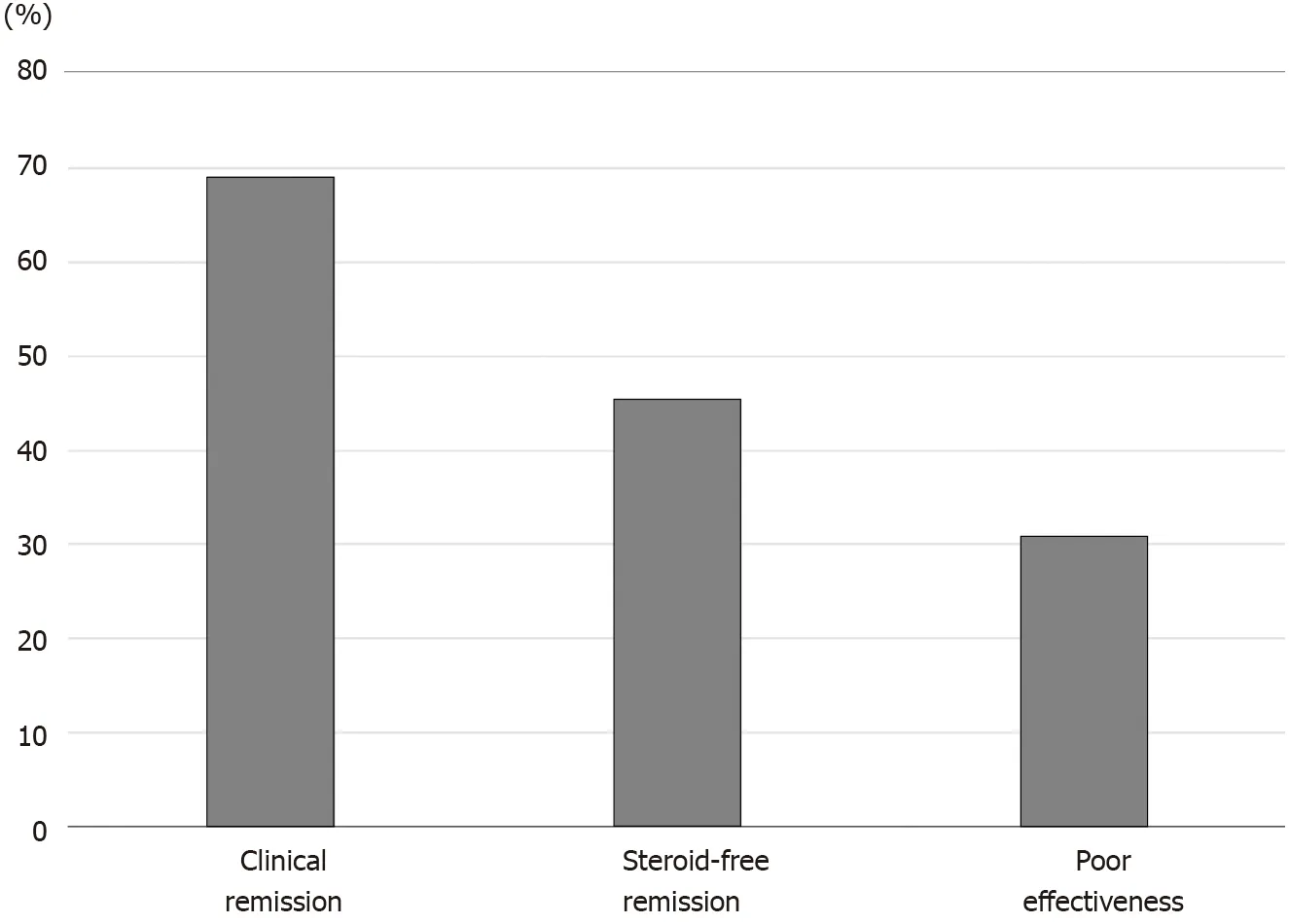

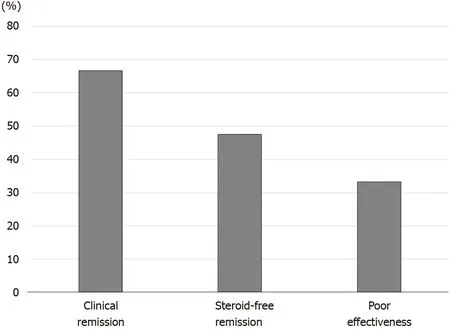

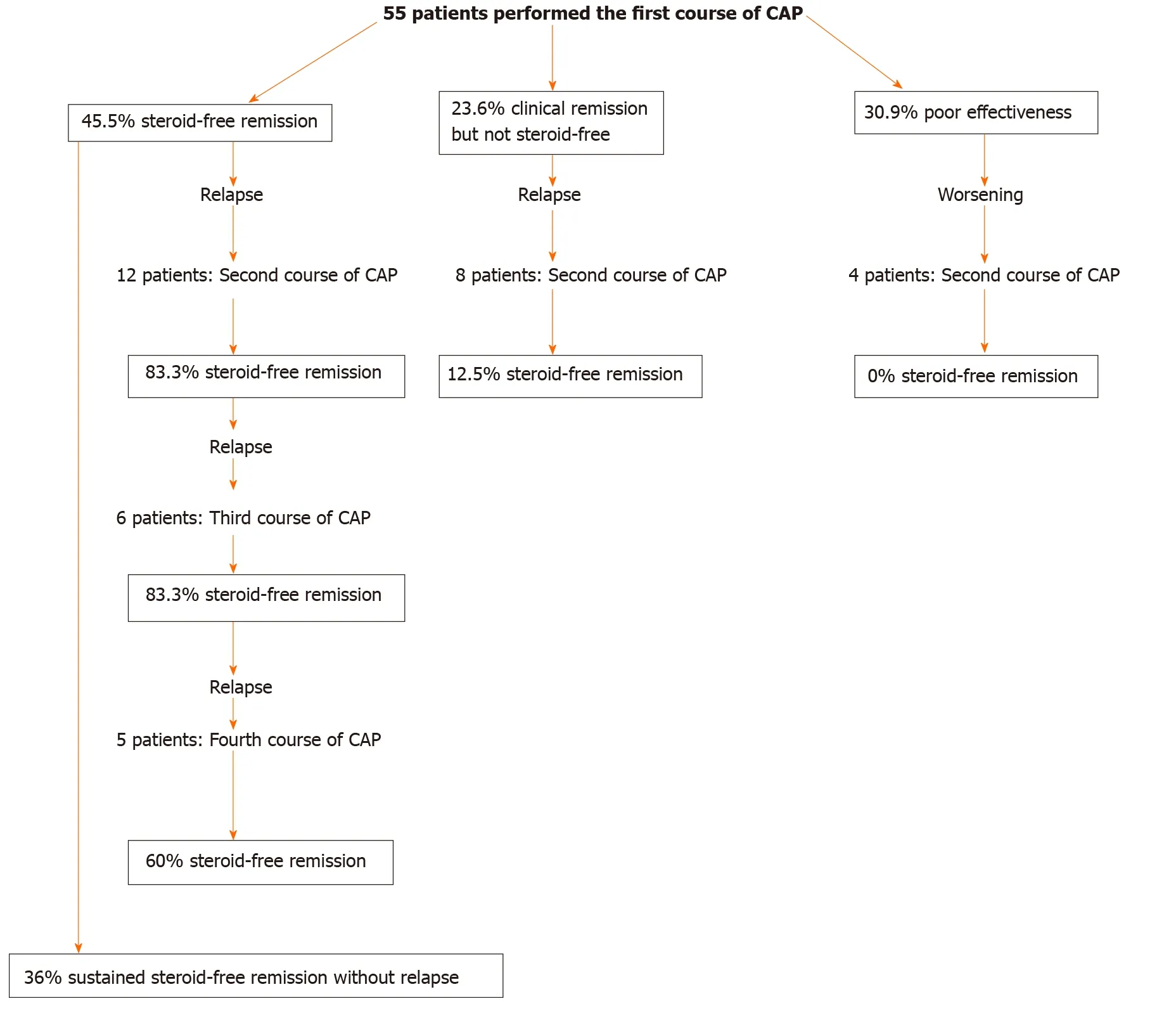

The rates of clinical remission, which includes steroid-free remission and clinical remission but not steroid-free remission, steroid-free remission, and poor effectiveness after CAP were 69 .1 %, 45 .5 %, and 30 .9 %, respectively (Figure 1 ). The rates of clinical remission, steroid-free remission, and poor effectiveness after GMA were 69 .2 %,43 .6 %, and 30 .8 %, respectively. The rates of clinical remission, steroid-free remission,and poor effectiveness after LCAP were 68 .8 %, 50 .0 %, and 31 .2 %, respectively. There were no significant differences in the rates of both clinical remission and steroid-free remission after CAP between patients who received GMA therapy and patients who received LCAP.

In this study, thiopurines were concomitantly used in 12 patients. The rates of clinical remission, steroid-free remission, and poor effectiveness after CAP in patients who concomitantly received thiopurines were 66 .7 %, 41 .7 %, and 33 .3 % respectively.There were no significant differences in the rates of both clinical remission and steroidfree remission after CAP between patients who concomitantly received thiopurines and patients who did not receive thiopurines.

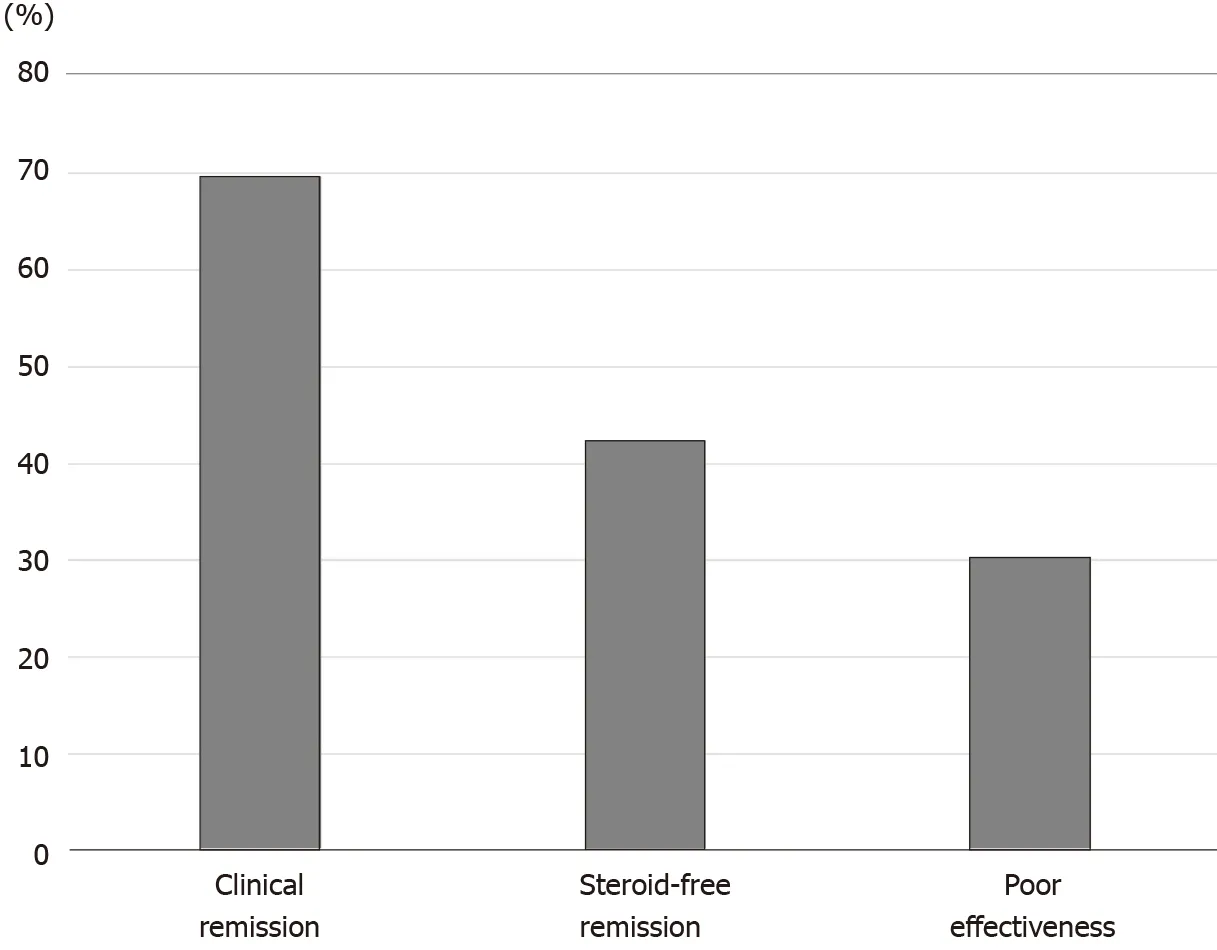

For patients with steroid-dependent UC, the rates of clinical remission, steroid-free remission, and poor effectiveness after CAP were 69 .7 %, 42 .4 %, and 30 .3 %,respectively (Figure 2 ). On the contrary, the rates of clinical remission, steroid-free remission, and poor effectiveness after CAP in patients with steroid-refractory UC were 66 .7 %, 47 .6 %, and 33 .3 %, respectively (Figure 3 ). There were no significant differences in both rates of clinical remission and steroid-free remission between patients with steroid-dependent UC and patients with steroid-refractory UC.

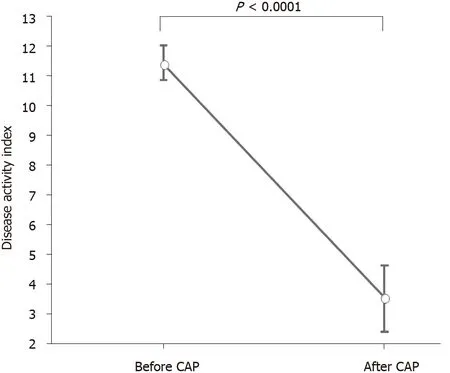

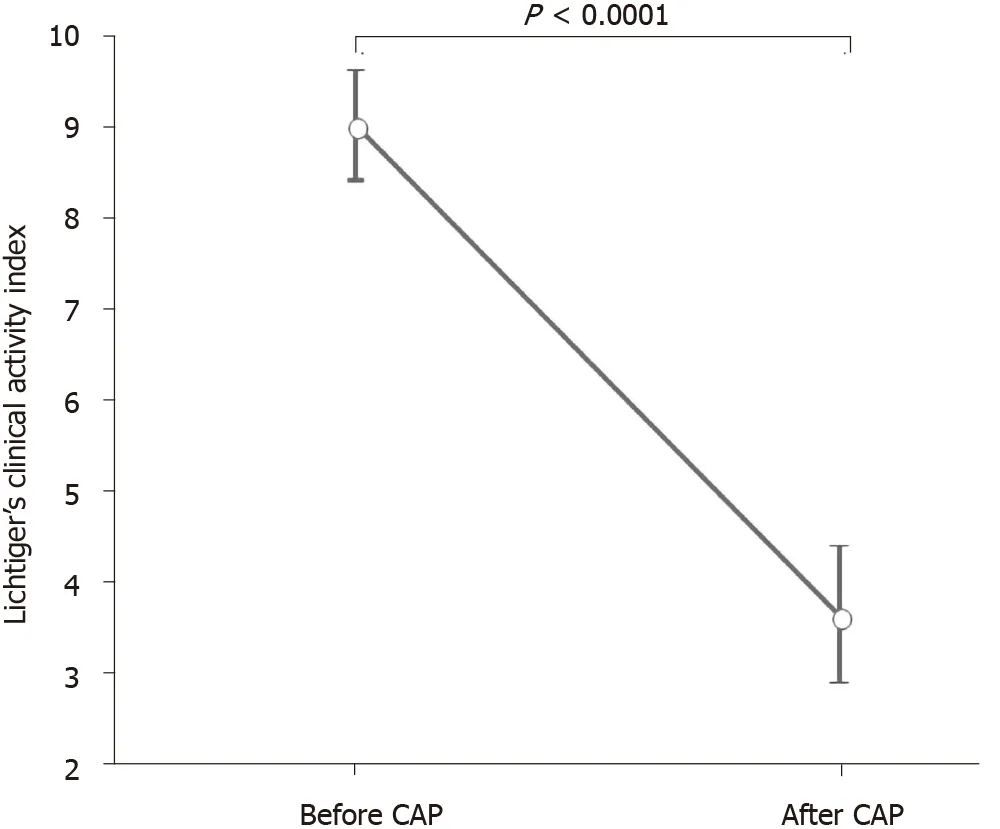

DAI and CAI scores (mean ± SE) before and after the first course of CAP are shown in Figures 4 and 5 . The mean DAI score before CAP was 11 .4 , which decreased significantly to 3 .36 after the CAP therapy (P < 0 .0001 ) (Figure 4 ). The mean CAI score before CAP was 9 .0 , which decreased significantly to 3 .63 after the CAP therapy (P <0 .0001 ) (Figure 5 ).

Laboratory data before and after CAP are shown in Table 2 . As shown in Table 2 ,the inflammatory parameter (C-reactive protein) and the nutritional parameter (serum albumin concentration) significantly improved after CAP. Neutrophil count significantly decreased after CAP therapy. Monocyte count tended to decrease after CAP, but no significant difference was observed.

The rates of steroid-free remission after the second course of CAP

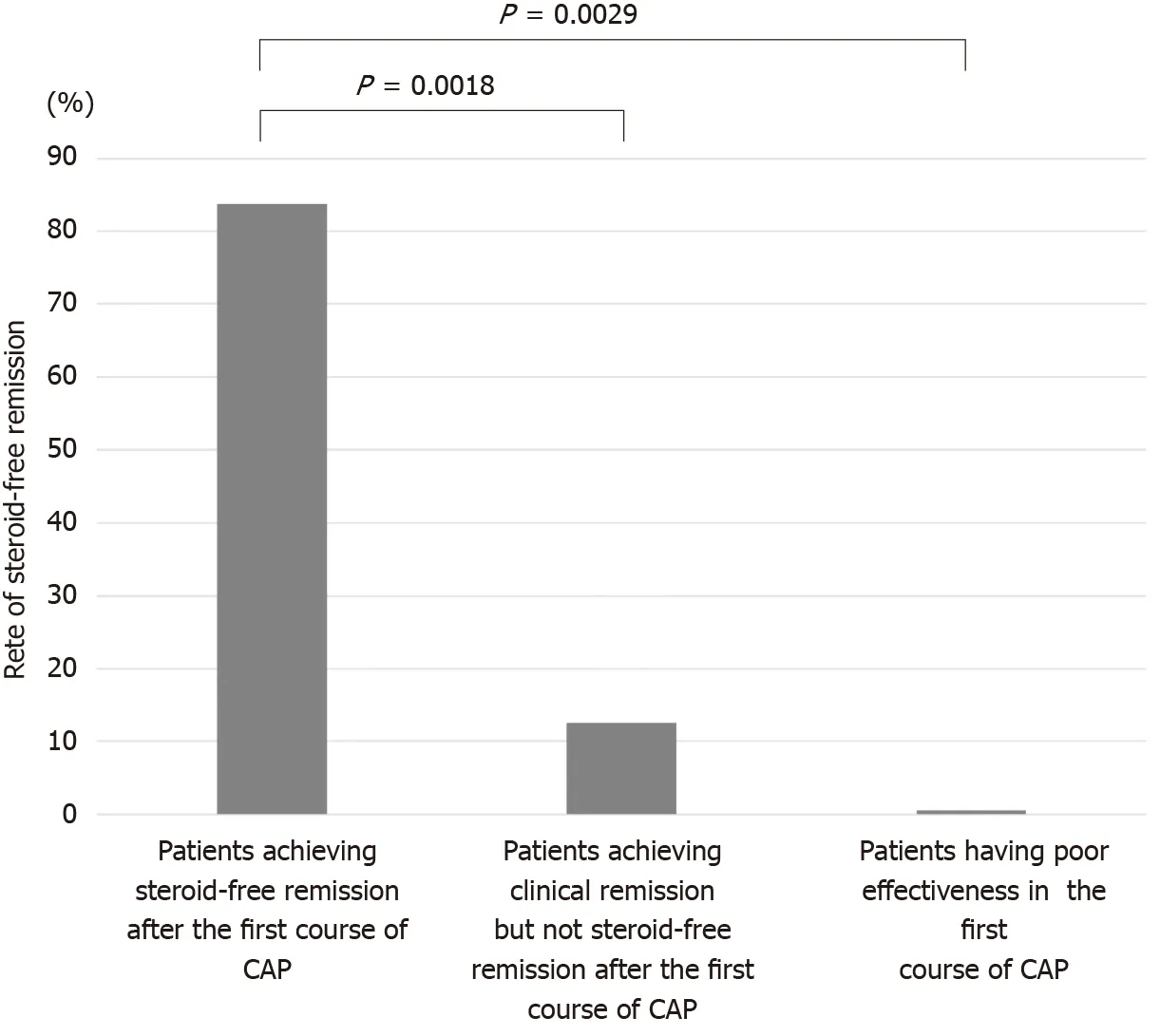

The second course of CAP was performed in 24 patients (12 patients who achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP, 8 patients who achieved clinical remission but not steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP, 4 patients who had poor effectiveness in the first course of CAP) experiencing a relapse or worsening condition during the observation period. The rates of steroid-free remission after the second course of CAP in patients who achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP, patients who achieved clinical remission but not steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP, and patients who had poor effectiveness in the first course of CAP were 83 .3 % (10 /12 ), 12 .5 % (1 /8 ), and 0 % (0 /4 ), respectively (Figure 6 ).The rate of steroid-free remission after the second course of CAP was significantly higher in patients who achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP compared with that in patients who achieved clinical remission but not steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP (P = 0 .0018 ) and that in patients who had poor effectiveness in the first course of CAP (P = 0 .0029 ).

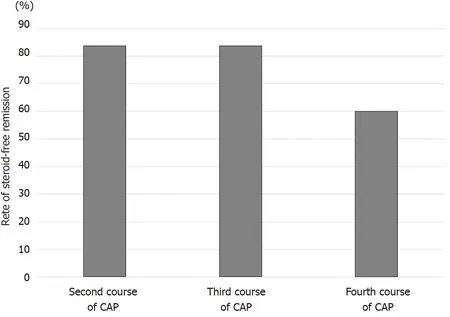

The rates of steroid-free remission after the second, third, and fourth courses of CAP in patients who achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP

As shown above, the rate of steroid-free remission after the second course of CAP in patients who achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP was 83 .3 %.In these patients, the rate of steroid-free remission after the second course of CAP in patients with steroid-dependent UC (83 .3 %) was the same as that of patients with steroid-refractory UC (83 .3 %).

The third and fourth courses of CAP were performed in 6 patients and 5 patients,respectively, who achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP and experienced relapses during the observation period. The rates of steroid-free remission after the third and fourth courses of CAP in these patients were 83 .3 % (5 /6 ) and 60 %(3 /5 ), respectively (Figure 7 ).

Table 2 Laboratory data obtained (mean ± SE) before and after cytapheresis

Figure 1 Efficacy of the first course of cytapheresis. The rates of clinical remission, which includes steroid-free remission and clinical remission without steroid-free remission, steroid-free remission, and poor effectiveness after cytapheresis were 69 .1 %, 45 .5 %, and 30 .9 %, respectively.

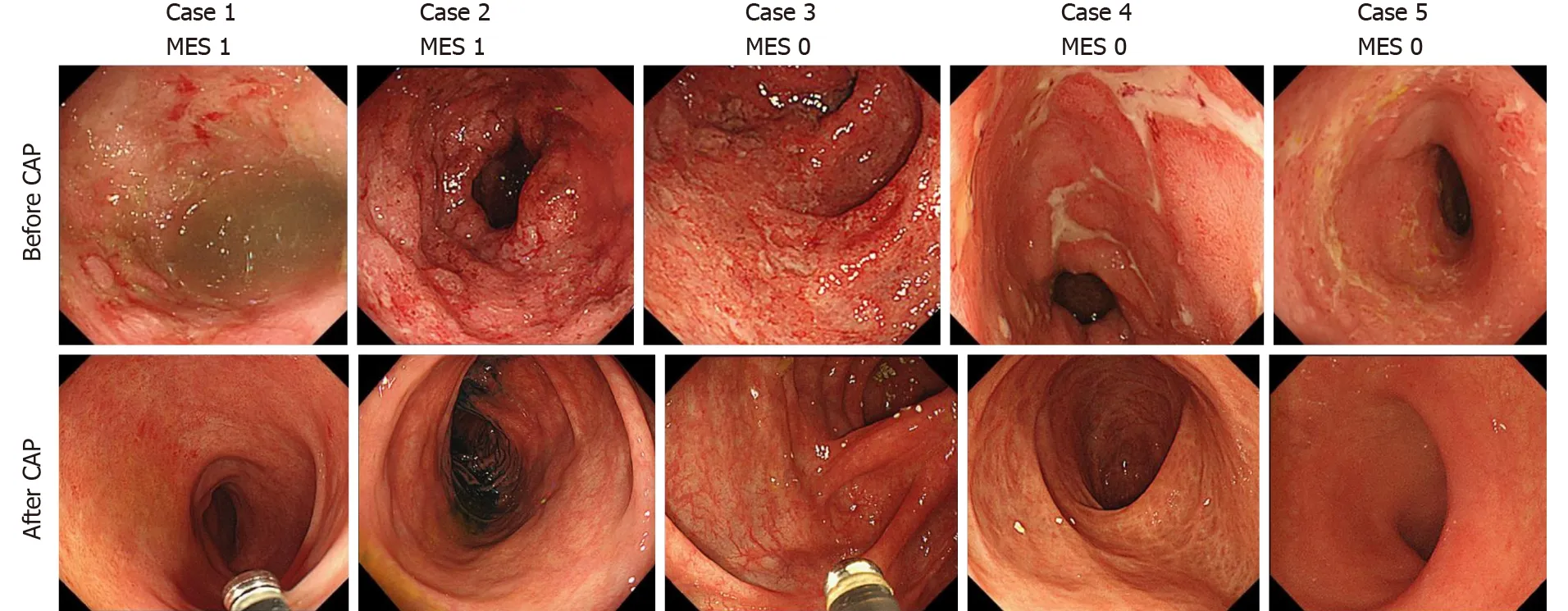

Endoscopic findings of patients who achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP

Colonoscopic examination was performed in 21 out of the 25 patients (84 %) who achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP. Mucosal healing was observed in all 21 patients after the first course of CAP [Mayo endoscopic subscore 0 in 17 patients (81 .0 %), Mayo endoscopic subscore 1 in 4 patients (19 .0 %)]. None of the patients showed a Mayo endoscopic subscore ≥ 2 after the CAP. Endoscopic images before and after the CAP therapy of 5 patients are shown in Figure 8 .

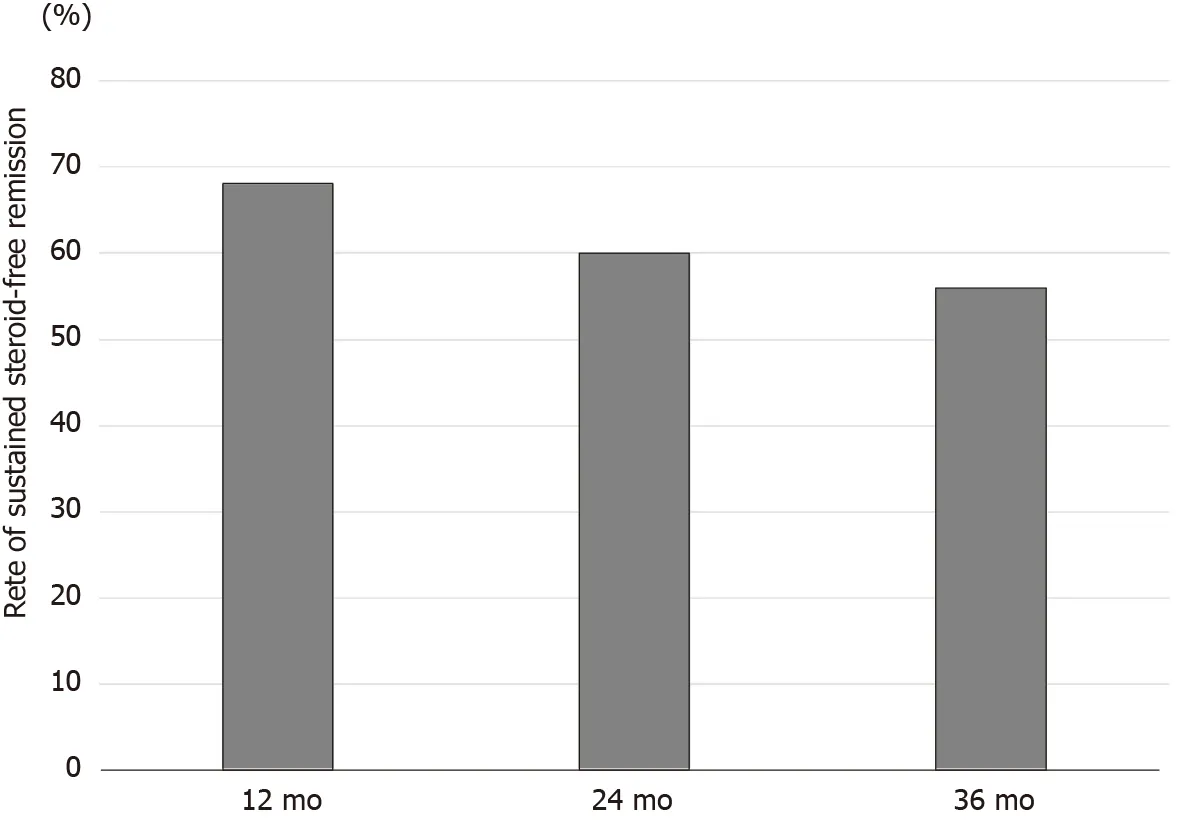

Long-term efficacy of CAP in patients achieving steroid-free remission in the first course of CAP

We could correctly follow the rate of sustained steroid-free remission for 3 years (36 mo) in all 25 patients who successfully achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP. The rates of sustained steroid-free remission in these patients were 68 .0 % at 12 mo, 60 .0 % at 24 mo, and 56 .0 % at 36 mo after the first course of CAP(Figure 9 ). The rates of sustained steroid-free remission in patients with steroiddependent UC were 69 .2 % at 12 mo, 53 .8 % at 24 mo, and 46 .1 % at 36 mo, respectively.On the other hand, the rates of sustained steroid-free remission in patients with steroid-refractory UC were 63 .6 % at 12 mo, 63 .6 % at 24 mo, and 63 .6 % at 36 mo,respectively.

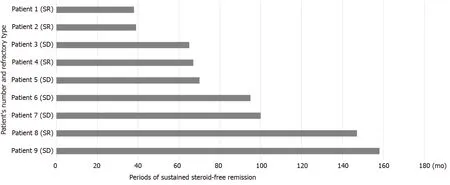

The mean observation period of these 25 patients was 81 .5 ± 9 .7 mo (mean ± SE).Although the observation periods varied in these 25 patients, 9 patients (36 .0 %) had maintained sustained steroid-free remission throughout the observation periods. The mean period of maintained steroid-free remission of these 9 patients was 86 .6 ± 14 .3 mo (mean ± SE). Periods of sustained steroid-free remission and refractory type of the 9 patients are shown in Figure 10 . Two patients had maintained sustained steroid-free remission over 10 years after the first course of CAP. The summary of the results of this study is shown in Figure 11 .

Figure 2 Efficacy of the first course of cytapheresis in the patients with steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis. The rates of clinical remission,steroid-free remission, and poor effectiveness after cytapheresis were 69 .7 %, 42 .4 %, and 30 .3 %, respectively.

Figure 3 Efficacy of the first course of cytapheresis in the patients with steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis. The rates of clinical remission,steroid-free remission, and poor effectiveness after cytapheresis were 66 .7 %, 47 .6 %, and 33 .3 %, respectively.

The surgical operation rates

The surgical operation rate of the patients within 6 mo after the first course of CAP was 9 .1 % (5 /55 ). The surgical operation rate within 6 mo after the CAP was significantly lower in patients who achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP (0 %) compared with that in patients who had poor effectiveness in the first course of CAP (29 .4 %) (P = 0 .0039 ). The surgical operation rate within 3 years after the first course of CAP was 12 .7 % (7 /55 ). The surgical operation rate within 3 years after the CAP was significantly lower in patients who achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP (4 %) compared with that in patients who had poor effectiveness (29 .4 %) (P = 0 .0209 ). The surgical operation rate throughout the observation period [18 -193 mo (81 .5 ± 47 .3 (mean ± SD)] after the first course of CAP was 20 % (11 /55 ). The surgical operation rate throughout the observation period after the CAP was significantly lower in patients who achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP (12 %) compared with that in patients who had poor effectiveness in the first course of CAP (41 .2 %) (P = 0 .0293 ).

Figure 4 Mean disease activity index score before and after cytapheresis. Disease activity index score (mean ± SE) before and after cytapheresis is shown. The mean disease activity index score before cytapheresis was 11 .4 , which decreased significantly to 3 .36 after treatment (P < 0 .0001 ). CAP: Cytapheresis.

Figure 5 Mean Lichtiger’s clinical activity index score before and after cytapheresis. Lichtiger’s clinical activity index score (mean ± SE) before and after cytapheresis is shown. The mean Lichtiger’s clinical activity index score before cytapheresis was 9 .0 , which decreased significantly to 3 .63 after treatment (P <0 .0001 ). CAP: Cytapheresis.

Adverse events

Headache and slight fever were observed in one patient during the CAP therapy. No serious adverse events were observed in all patients in this study.

DISCUSSION

Figure 6 The rates of steroid-free remission after the second course of cytapheresis. The rate of steroid-free remission after the second course of cytapheresis (CAP) was significantly higher in patients who achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP (83 .3 %) compared with that in patients who achieved clinical remission but not steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP (12 .5 %, P = 0 .0018 ) and that in patients who had poor effectiveness after the first course of CAP (0 %, P = 0 .0029 ). CAP: Cytapheresis.

Figure 7 Rates of steroid-free remission after the second, third, and fourth courses of cytapheresis in patients who achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of cytapheresis. The rates of steroid-free remission after the second, third, and fourth courses of cytapheresis in patients who achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of cytapheresis and then experienced relapses were 83 .3 %, 83 .3 %, 60 %, respectively. CAP: Cytapheresis.

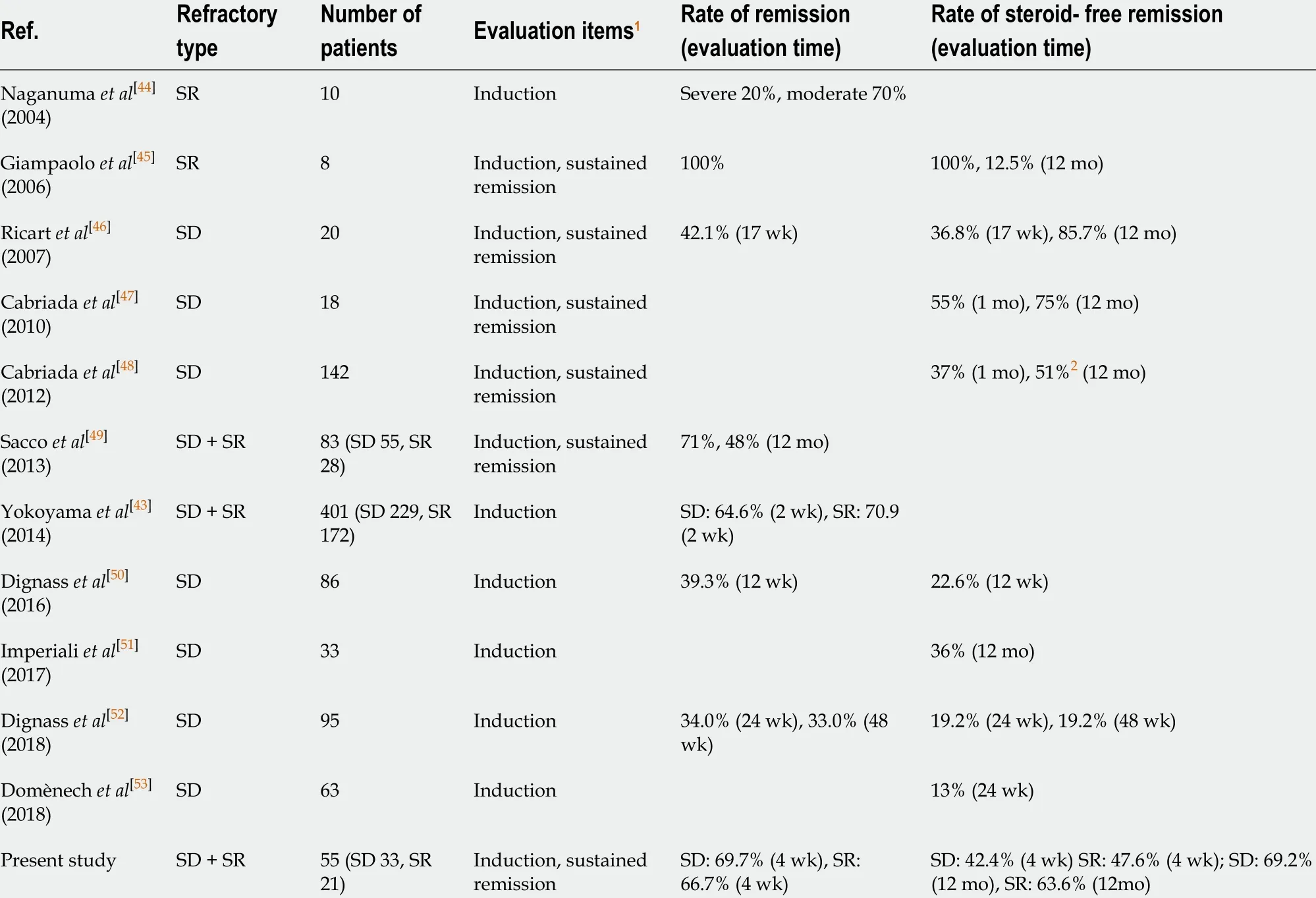

The primary endpoint of this study was the rate of achievement of steroid-free remission in refractory UC patients after the CAP therapy. In this context, we demonstrated that CAP effectively induced steroid-free remission not only in patients with steroid-dependent (42 .4 %) but also in patients with steroid-refractory (47 .6 %) UC.We also showed that mucosal healing was observed in all patients who achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP. Previous studies examining the efficacy of CAP in refractory UC and the results of this study are shown in Table 3 [43 -53].In these studies, eight studies[45 -48 ,50 -53]examined the efficacy of CAP for induction of steroid-free remission and three studies[43 ,44 ,49]examined that for induction of only clinical remission. Here, we discuss the eight studies examining the efficacy of CAP for induction of steroid-free remission. In the eight studies, seven studies[46 -48 ,50 -53]examined the rate of the induction of steroid-free remission in patients with steroid-dependent UC and one study[45]examined that in patients with steroid-refractory UC. Regarding steroid-refractory UC, it is difficult to evaluate the results of the study because there is only one study, which only comprised eight steroid-refractory patients, that assessedthis type of UC[45]. With regard to steroid-dependent UC, according to the seven previous studies[46 -48 ,50 -53], the rates of the induction of steroid-free remission ranged from 13 % to 55 % (mean 31 .4 %). Although it is difficult to compare the results of these studies with that of our study because of the diversity of the patients’ background enrolled in the studies, the rate of the induction of steroid-free remission of our study is higher than that of the six previous studies[46 ,48 ,50 -53]. Based on the following reports[43 ,46 ,50], we suggest that the differences of the history of previous medication and the differences of the methods of CAP treatment of the studies might influence the rates of steroid-free remission. Dignass et al[50]showed that remission was achieved at week 12 after Adacolumn apheresis by 40 .3 % of patients who failed on immunosuppressants, but only 27 .8 % of patients who failed on anti-TNF-α treatment.On the other hand, Yokoyama et al[43]showed that a multivariate logistic regression analysis comparing the patients’ backgrounds, concomitant medications, and therapeutic variables of LCAP between the remission and nonremission groups identified intensive LCAP (≥ 4 LCAP treatments within the first 2 wk) as the only factor that was significantly related to remission after LCAP. On the contrary, Ricart et al[46]showed that increasing the number of apheresis sessions affords a significant steroid-sparing effect in steroid-dependent UC. Looking back with reference to these reports, in our study, only one patient who had insufficient response to anti-TNF-α treatment was included, and intensive CAP was performed in some severe cases in contrast to the six previous studies[46 ,48 ,50 -53]performing weekly apheresis in all patients.Additionally, it appears that patients in our study received more CAP sessions [5 -20 sessions (mean 8 .8 )] compared with the previous studies. We suggest that a selection of an appropriate CAP treatment method for each patient is important to induce steroid-free remission effectively in refractory UC patients.

Table 3 Previous studies examining the efficacy of cytapheresis in refractory ulcerative colitis

Figure 8 Endoscopic images of 5 patients who achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of cytapheresis. Endoscopic images before and after the cytapheresis (CAP) therapy of 5 patients who achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP are shown. Active inflammation (Mayo endoscopic subscore ≥ 2 ) was observed in the colonic mucosa in all 5 patients before the CAP therapy. On the contrary, mucosal healing (Mayo endoscopic subscore ≤ 1 ) was observed in all 5 patients after the CAP therapy. MES: Mayo endoscopic subscore; MES 1 /MES 0 : Mayo endoscopic subscore after cytapheresis;CAP: Cytapheresis.

Figure 9 Rates of sustained steroid-free remission at 12 , 24 , and 36 mo after the first course of cytapheresis in patients who achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of cytapheresis. The rates of sustained steroid-free remission in patients who achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of cytapheresis were 68 .0 % at 12 mo, 60 .0 % at 24 mo, and 56 .0 % at 36 mo after the first course of cytapheresis.

Regarding the achievement of steroid-free remission, assessing the rate of reinduction of steroid-free remission with CAP in patients who experience relapse after the first course of CAP is also required. In this regard, our study showed that the second course of CAP effectively re-induced steroid-free remission (83 .3 %) in both steroid-dependent and steroid-refractory UC patients who had achieved steroid-free remission in the first course of CAP. The rate of re-induction of steroid-free remission was significantly higher in patients who achieved steroid-free remission in the first course of CAP (83 .3 %) compared with that of patients who had achieved clinical remission but not steroid-free remission (12 .5 %) and that of patients who had poor effectiveness in the first course of CAP (0 %). Furthermore, our study also showed that the third and the fourth courses of CAP repeatedly induced steroid-free remission at a high rate in patients who achieved steroid-free remission in the first course of CAP.Based on these results, we suggest that patients achieving steroid-free remission in the first course of CAP are significantly likely to have a high sensitivity to CAP, namely,high responders to CAP. There have been no studies assessing the rate of re-induction of steroid-free remission of CAP in patients with steroid-dependent and steroidrefractory UC. However, there have been two studies that examined the re-efficacy of CAP in patients with active UC or Crohn’s disease (CD)[37 ,41 ]. Takayama et al[41]examined the effects of the second course of CAP in UC patients with moderate to severe activity experiencing relapse during the disease course. They showed that the percentage of remissive and effective responses of the second course of CAP was 79 %in patients who had remissive and effective responses in the first course of CAP,whereas 40 % in patients who had noneffective responses in the first course of CAP.Lindberg et al[37 ] presented 14 patients (UC 4 , CD 10 ) who experienced relapse after showing initial remission and were re-treated with GMA. Although the remission rates of the re-treatments of GMA in UC patients were unclear, they showed that 13 of the 14 patients (93 %) achieved a second remission. They also showed that following further relapses, all patients were successfully re-treated with GMA for the third,fourth, and fifth time. Thus, the previous two studies also showed that re-treatment of CAP seemed to be effective in UC patients who had remissive responses in the first course of CAP, supporting our results.

Figure 10 Periods of sustained steroid-free remission and refractory type of the 9 patients who had maintained steroid-free remission throughout the observation periods. Nine patients (36 .0 %) had maintained sustained steroid-free remission throughout the observation periods. Periods of sustained steroid-free remission of the 9 patients are shown in the figure. The mean period of maintained steroid-free remission of these 9 patients was 86 .6 ± 14 .3 mo (mean ± SE). Nine patients included 5 steroid-dependent patients and 4 steroid-refractory patients. Periods of sustained steroid-free remission of the 9 patients are shown in the figure. SR: Steroid-refractory patient; SD: Steroid-dependent patient.

The secondary endpoint of this study was the rate of sustained steroid-free remission in refractory UC patients after the CAP therapy. In this regard, we showed that CAP had good long-term efficacy for the maintenance of sustained steroid-free remission (68 % at 12 mo, 60 % at 24 mo, 56 % at 36 mo) in refractory UC patients who achieved steroid-free remission in the first course of CAP. Furthermore, interestingly,36 % of patients had maintained sustained steroid-free remission throughout the observation periods, and two patients had maintained it over 10 years. Previous studies examining the rate of sustained steroid-free remission after the CAP therapy in refractory UC patients are also shown in Table 3 . Among them, three studies examined the rate of sustained steroid-free remission in patients with steroid-dependent UC[46 -48].The rates of sustained steroid-free remission at 12 mo after CAP of the three studies ranged from 51 % to 85 .7 % (mean 70 .6 %). Thus, these studies and our study (69 .2 % in steroid-dependent patients) showed good long-term efficacy in the rates of sustained steroid-free remission. In this regard, in our study, mucosal healing was observed in all patients who achieved steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP. Ricart et al[46]also showed that all patients who experienced clinical remission also experienced endoscopic remission and good long-term efficacy. Cabriada et al[48]showed that among those patients in steroid-free remission, 96 % also achieved endoscopic remission. They also showed that a tendency for sustained remission at 1 year was observed when initial endoscopic remission was achieved[47]. Based on these findings, we suggest that endoscopic mucosal healing was closely involved in the maintenance of sustained steroid-free remission and good long-term efficacy of CAP.

In this study, no serious adverse events were observed during the CAP therapy. It has been reported that other therapies, such as anti-TNF-α antibody administration,are associated with risk of serious infections, lymphoma, and associated mortality in IBD[28 ,29 ,50]. In this context, several studies reporting on the safety of CAP have been considered important[39 ,42 ,43 ,49 ,50 ]. Among these studies, Hibi et al[39]evaluated the safety and clinical efficacy of Adacolumn in 697 patients with UC in 53 medical institutions.They showed that no serious adverse events were observed, and mild to moderate adverse events were observed in 7 .7 % of patients. Motoya et al[42]conducted a retrospective multicenter cohort study that evaluated the safety and effectiveness of GMA in 437 IBD patients under special situations. They showed that the incidence of adverse events among elderly patients was similar in all patients.

Figure 11 Summary of the results of the study. The results of this study are summarized in the figure. CAP: Cytapheresis.

There have been several studies comparing the impact of CAP in the clinical practice with the conventional pharmacotherapy for UC[53 ,62 -64]. A meta-analysis showed that GMA is effective for inducing clinical remission in patients with UC compared with CS [odds ratio (OR), 2 .23 ; 95 % confidence interval (CI): 1 .38 -3 .60 ] and that the rate of adverse events by apheresis was significantly lower than that by CS(OR, 0 .24 ; 95 %CI: 0 .15 -0 .37 )[62]. Another meta-analysis showed that comparing with conventional pharmacotherapy including CS, LCAP supplementation presented a significant benefit in promoting a response rate (OR, 2 .88 , 95 %CI: 1 .60 -5 .18 ) and remission rate (OR, 2 .04 , 95 %CI: 1 .36 -3 .07 ) together with significant higher steroidsparing effects (OR, 10 .49 , 95 %CI: 3 .44 -31 .93 ) in patients with active moderate-tosevere UC[63 ]. In this regard, Domènech et al[53 ] showed that the addition of 7 weekly sessions of GMA to a conventional course of oral prednisolone did not increase the proportion of steroid-free remissions in patients with active steroid-dependent UC. On the other hand, Tominaga et al[64]showed that GMA produced efficacy equivalent to prednisolone and was without safety concern. Although they also showed that the average medical cost was 12739 .4 €/patient in the GMA group and 8751 .3 € in the prednisolone group (P < 0 .05 ), they concluded that the higher cost of GMA vs prednisolone should be compromised by good safety profile of GMA.

In summary, our study showed that CAP was effective in inducing steroid-free remission and maintained sustained steroid-free remission in both steroid-dependent and steroid-refractory UC patients. Additionally, our study also showed that CAP reinduced high-rate steroid-free remission repeatedly in patients who achieved steroidfree remission in the first course of CAP, namely, patients potentially having a high sensitivity to CAP. Therefore, considering the high level of safety of CAP, we suggest that CAP should be one of the first-line therapies for steroid-dependent and steroidrefractory UC patients. We also suggest that CAP should be chosen as a first-line therapy for patients who achieve steroid-free remission in the first course of CAP and thereafter experience relapses during the disease course.

However, this study has some limitations; that is, this study is a retrospective study with small sample size that was conducted only in two medical institutions. Thus, a multicenter prospective study with large sample sizes is required to warrant our results.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our results suggest that CAP effectively induces and maintains steroidfree remission in refractory UC and re-induces high-rate steroid-free remission repeatedly in patients achieving steroid-free remission after the first course of CAP.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research perspectives

A multicenter prospective study with large sample sizes is required to warrant our results.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Dr. Koizumi S (Center for Cancer Registry and Information Services in Akita University Hospital) for biostatical review of the study.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2021年12期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2021年12期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Perioperative blood transfusion decreases long-term survival in pediatric living donor liver transplantation

- Emerging wearable technology applications in gastroenterology: A review of the literature

- Primary localized gastric amyloidosis: A scoping review of the literature from clinical presentations to prognosis

- Hepatitis E in solid organ transplant recipients: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Risk stratification and geographical mapping of Brazilian inflammatory bowel disease patients during the COVID-19 outbreak: Results from a nationwide survey

- Risk perception and knowledge of COVID-19 in patients with celiac disease