Long-term follow-up of cumulative incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis B virus patients without antiviral therapy

Xiao-Yan Jiang, Bing Huang, Dan-Ping Huang, Chun-Shan Wei, Wei-Chao Zhong, De-Ti Peng, Fu-Rong Huang, Guang-Dong Tong

Abstract

Key Words: Chronic hepatitis B; Anti-inflammatory therapy; Hepatoprotective therapy; Cumulative incidence; Hepatocellular carcinoma; Antiviral therapy

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 45% of hepatocellular carcinomas (HCCs) in patients worldwide and 80% of HCCs in patients in China are caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection[1]. According to the World Cancer Report published by the World Health Organization in 2014, the number of new cases of and deaths from HCC in China accounted for more than half of the total global number in 2012[2]. The high prevalence of HCC in China is mainly due to HBV infection[3,4].

Early studies suggest that effective antiviral therapy can reduce the incidence of HCC in patients with hepatitis B cirrhosis[5-7]. A clinical study in Hong Kong included 1446 patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) (including 482 patients with cirrhosis) who received entecavir treatment. The control group included 424 untreated patients (including 69 with cirrhosis). The cumulative incidence rates of HCC in patients with cirrhosis at 3 and 5 years were reduced in the treatment group[8]. Two studies in Japan showed similar results[9,10].

However, there is no consistent conclusion regarding the effect of antiviral therapy on reducing the incidence of HCC among patients with CHB without cirrhosis who have a low risk of HCC[11,12]. Many studies have found no significant reduction in the incidence of HCC in patients with CHB who benefit from antiviral therapy[13]. A Greek study followed up 818 patients with CHB. The results showed that 49 patients developed HCC and that the cumulative incidence of HCC at 5 years was 3.2%. The incidence rates of HCC among patients aged < 50 years, 50-60 years and > 60 years were 0.7%, 6.7% and 11.7%, respectively. Antiviral therapy did not reduce the incidence of HCC associated with age. Multivariate analysis showed that age, sex and cirrhosis were independent risk factors for HCC, regardless of antiviral therapy[14]. A recent Caucasian study found that among 1666 patients with CHB who received entecavir or tenofovir antiviral therapy, the incidence rates of HCC at 1, 3 and 5 years were 1.3%, 3.4% and 8.7%, respectively[15]. The cumulative incidence of HCC has been increasing even with HBV suppression. With the prolongation of follow-up, the incidence of HCC is predicted to increase.

The occurrence of HCC is related to a high viral load and to a long-term and continuous increase in alanine aminotransferase (ALT). The REVEAL study suggested that HCC is associated with a sustained increase in serum ALT levels[16]. Elevated ALT is an indicator of hepatocyte injury or inflammation. Liver fibrosis and cirrhosis caused by chronic liver inflammation are the pathophysiological and histological bases for HCC progression in patients with hepatitis B[17]. Patients with CHB and persistent or repeated elevations in ALT have significantly higher risks of cirrhosis, hepatic decompensation, and HCC than those with persistently normal ALT levels or with fluctuations that return to normal[18,19].

Anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective therapy is an important approach for CHB in China[20]and effectively inhibits the inflammatory response of the liver and promotes repair of damaged hepatocytes. Studies have shown that anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective therapy can delay or even prevent the development of CHB into cirrhosis, indicating its high clinical value[21,22]. Antiviral therapy is also effective in controlling liver inflammation, but the ALT levels of 20% of patients still fail to return to normal afterwards[23]. Abnormal ALT levels during the first year of treatment in patients with CHB are associated with an increased risk of HCC[23].

In China, there are approximately 30 million patients with CHB, but only 11% of these patients receive standardized antiviral therapy[24]. Currently, there are few relevant reports addressing the outcomes of the large number of CHB patients who do not receive antiviral therapy. In our observation group, we included 362 patients with CHB and 96 with hepatitis B cirrhosis who were not treated with antiviral therapy but had been treated with anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective drugs for a long time. The median follow-up times were 10 and 7 years, respectively. A total of 203 patients with CHB and 129 patients with hepatitis B cirrhosis receiving antiviral therapy were included as the control group. The median follow-up times were 8 and 7 years, respectively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Observation group

This study comprised 3500 patients with CHB who were hospitalized for the first time in the Department of Hepatology, Shenzhen Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine between January 1993 and December 1998 due to abnormal liver function (ALT ≥ 40 U/L). According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we enrolled 362 patients with CHB and 96 patients with cirrhosis who were treated with anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective drugs without antiviral therapy. The median HBV-DNA (log) load was 7.14, and the median ALT level was 188.62 U/L. These patients should have been treated with antiviral therapy, but for various reasons, they did not receive antiviral therapy.

Control group

We collected data for 3897 patients with CHB who received antiviral therapy when they were admitted to the Department of Shenzhen Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine between January 1999 and December 2007 and who received antiviral therapy at the initial visit. According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we enrolled 203 patients with CHB and 129 patients with hepatitis B cirrhosis.

Inclusion criteria

CHB without cirrhosis: (1) Patients were positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) for at least 6 mo; (2) Aged 18-75 years; (3) No treatment with interferon; (4) Patients with anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective drug treatment had ALT ≥ 2 upper limit of normal, HBV-DNA positivity and follow-up times ≥ 2 years; and (5) Patients with antiviral treatment had voluntary acceptance of nucleoside antiviral therapy, follow-up time of ≥ 2 years, and treatment with anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective drugs for ≤ 6 mo. Hepatitis B cirrhosis patients: (1) Cirrhosis diagnosed by imaging or histology at enrollment; and (2) Child-Turcotte-Pugh score ≥ 7 points defined as decompensated.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) CHB complicated by drug-induced liver damage, alcoholic liver disease, autoimmune liver disease or other liver diseases; (2) HCC; (3) Liver cancer diagnosed within 1 year after treatment; (4) Patients with antiinflammatory and hepatoprotective therapy who were followed up for < 2 years after treatment; and (5) Patients with antiviral treatment who were followed up for < 2 years or who received anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective treatment for > 6 mo.

Study design

This was an ambispective cohort study, with retrospective analyses before December 31, 2007, and prospective cohort analyses thereafter. The study was conducted and reported according to the study protocol, conforming to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, which was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shenzhen Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine. All of the included patients were required to give signed informed consent.

Treatment

Observation group: Treatment consisted of glycyrrhizin preparation (oral or intravenous injection), glutathione (oral or intravenous injection), schisandra preparation (oral bicyclol, wuzhi capsule or tablet), and Silymarin. Control group: monotherapy consisted of lamivudine (LAM) 100 mg/d (Galans history Ke Pharmaceutical Company), adefovir (ADV) 10 mg/d (GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals), telbivudine (LDT) 600 mg/d (Beijing Novartis Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.), or entecavir (ETV) 0.5 mg/d (China-US Shanghai Squibb Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.), and combination therapy consisted of an initial combination or salvage treatment, namely, LAM + ADV, LDT + ADV, or ETV + ADV.

Follow-up procedure

The starting point was the time when each patient was enrolled for the first time, and the endpoint of follow-up was the time of study discontinuation or last follow-up visit before the patient was lost to follow-up. All patients were followed up at least every 6 mo. The follow-up times of the patients with anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective treatment were ≥ 2 years. The addition of or switching between antiviral drugs was considered to be the endpoint of follow-up. Patients with antiviral therapy alone were not treated with anti-inflammatory or hepatoprotective therapy for ≥ 6 mo. The antiinflammatory and hepatoprotective therapy patients were followed up for 2-23 years (1993-2016), and antiviral patients were followed up for 2-17 years (1999-2016) (Figure 1). Follow-up observation indicators were: (1) Liver function: ALT, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and total bilirubin (TB); (2) HBV-DNA quantification; (3) HBV markers such as HBsAg and hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg); (4) Routine blood tests; (5) B-mode Doppler imaging, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); and (6) a-fetoprotein (AFP) detection.

Laboratory tests

Figure 1 Flow chart of the control group.

(1) Liver function was tested with an Olympus 2700 automatic biochemical analyzer, and routine analysis of blood was performed with an XS-500i automatic analyzer; (2) HBV marker detection was performed using an ELISA method, with reagents provided by Shanghai Kehua Bioengineering Co., Ltd; (3) HBV-DNA quantitative analysis was performed using real-time fluorescent quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and COBASTaqMan HBV diagnostic reagents, and the reagents were provided by Shenzhen Piji Bioengineering Co., Ltd. and Roche Diagnostics Co., Ltd. The instruments used were the ABI PRISM 7000 fluorescence quantitative PCR instrument and COBAS Taqman48analyzer real-time quantitative PCR analyzer; (4) AFP measurements were performed using enzyme immunoassays, with a normal detection value of 20 ng/L; (5) B-mode Doppler imaging was performed using the Fynergy-type color dual-function Doppler produced by the Tyson Corporation. The Bultrasound diagnostic criteria for cirrhosis were as follows: according to the integral classification standard of liver ultrasound parameters, the score was ≥ 10 points[25]; (6) Lesions in the liver were observed by B-ultrasound, CT and MRI. The CT spiral scanner was the Siemens Picker UltraZ super, and the MRI diagnostic instrument was the Philips intera2.0T, 3.0T high magnetic field superconducting magnetic resonance machine; and (7) For the liver biopsy specimens, the lengths were ≥ 1.5 cm, conventional paraffin sections were prepared for hematoxylin and eosin staining and Masson and reticulum fiber staining, and each specimen contained at least six junction areas.

Statistical analysis

This study used HCC as the endpoint of observation. The study deadline was December 31, 2016. The analysis of all patients with follow-up data and of those who were lost to follow-up was ended with the last clinical datapoints. For statistical analysis of differences between groups, qualitative data were analyzed using the c2test or Fisher’s exact probability method, and continuous variables were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test. The cumulative incidence of liver cancer was analyzed by Kaplan-Meier curves, and statistical significance was determined using the log-rank test. The Cox risk regression model was used to analyze the factors influencing liver cancer. All data were analyzed by SPSS version 22.0. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Clinical baseline data of enrolled patients

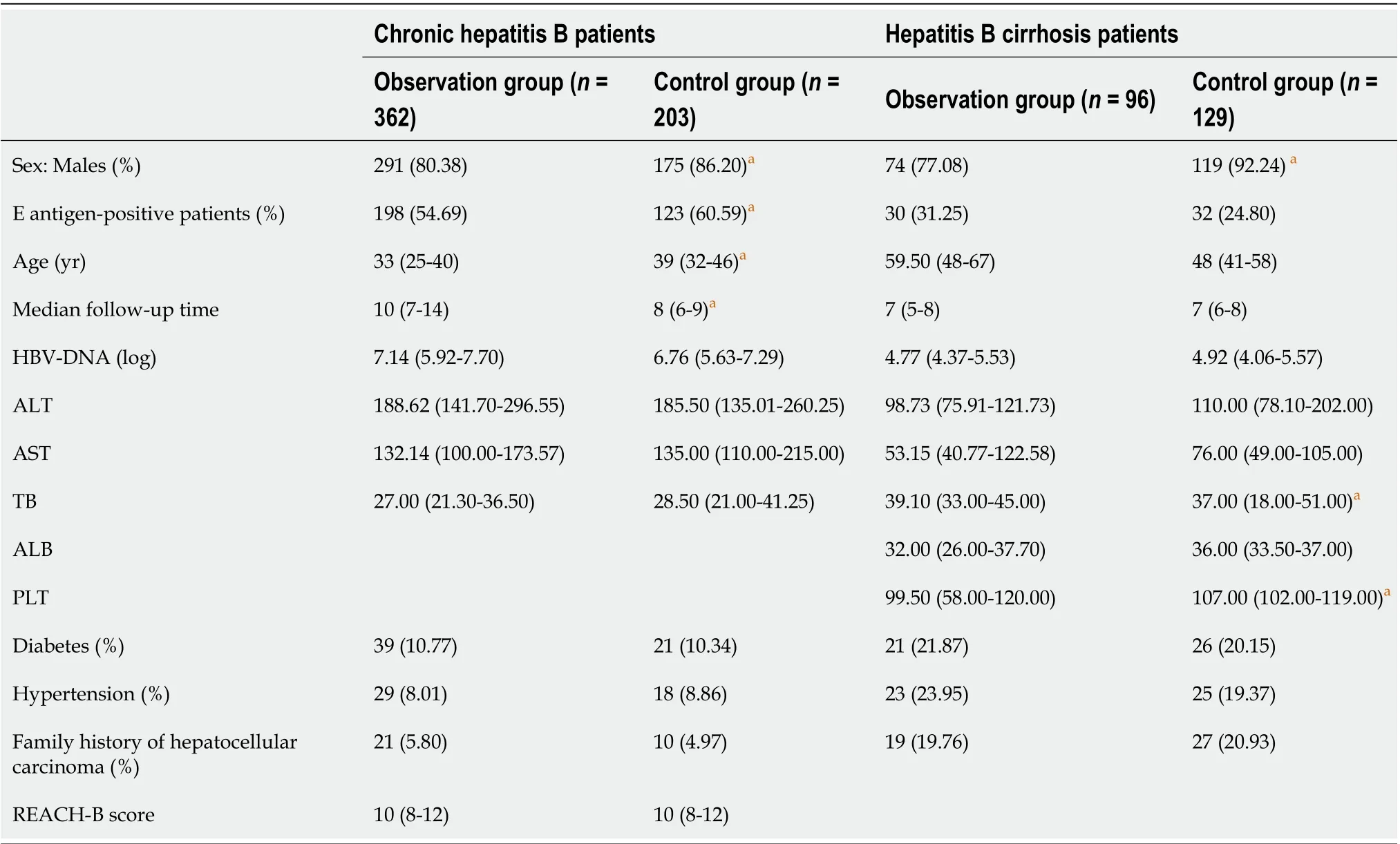

There were 291 men and 71 women among the 362 patients with CHB in the observation group. There were 175 men and 28 women in the control group. According to the statistical analysis, there were significant differences in sex between the two groups (P < 0.05). There were 198 HBeAg-positive patients in the observation group and 123 in the control group. The difference in the proportions of HBeAgpositive patients in the two groups was significant (P < 0.05). In the observation group, the median age was 33 years, and the median follow-up time was 10 years; in the control group, the median age was 39 years, and the median follow-up time was 8 years. There were significant differences in age and follow-up between the two groups (P < 0.05). However, there were no significant differences in the remaining indicators (Table 1).

In the observation group, there were 74 men and 22 women among the 96 patients with hepatitis B cirrhosis. In the control group, there were 119 men and 10 women among 129 patients with hepatitis B cirrhosis, and there were significant differences in sex between the two groups (P < 0.05). In the observation group, the median TB level was 39.10 mmol/L, and the median platelet count was 99.50 × 109/L. In the control group, the median TB level was 37.0 mmol/L, and the median platelet count was 107 × 109/L. There were significant differences in the TB and platelet levels between the two groups (P < 0.05). There were no significant differences in the other indicators (Table 1).

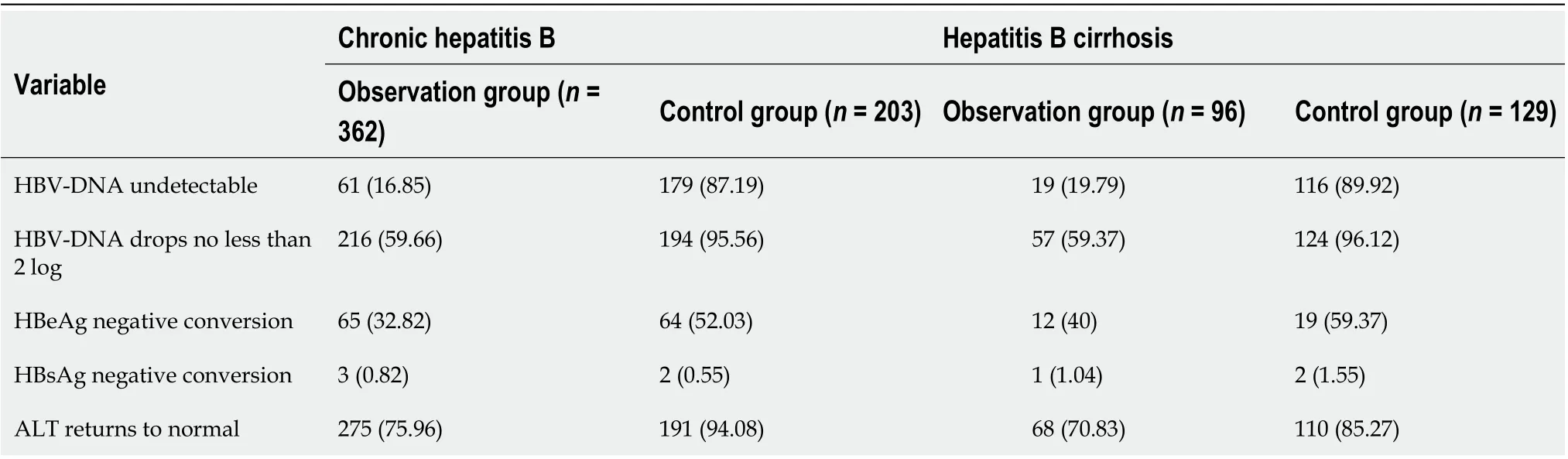

HBV-DNA, HBeAg, HBsAg and ALT testing at the end of follow-up

At the end of follow-up of the 362 CHB patients, HBV DNA was undetectable in 61 patients (16.6%) and decreased by no less than 2 Log in 216 patients (59.7%). Sixty-five patients (32.8%) were negative for HBeAg, three (0.8%) were negative for HBsAg, and 275 (76.0%) had normal ALT levels. However, among the 203 patients in the control group, 179 were HBV-DNA negative (87.2%), 194 (95.6%) had decreased HBV-DNA levels by no less than 2 Log, 64 (52.0%) were negative for HBeAg, two (0.6%) were negative for HBsAg, and 191 (94.1%) had normal ALT levels (Table 2).

At the end of the follow-up of the 96 patients with hepatitis B cirrhosis, 19 (19.8%) were negative for HBV DNA. Fifty-seven patients (59.37%) showed decreases in HBVDNA of no less than 2 Log, 12 (40.0%) had HBeAg negative conversion, one had HBsAg negative conversion (1.0%), and 68 patients (70.8%) had normal ALT levels. In the control group of 129 patients, 116 (89.9%) were HBV-DNA negative, 124 (96.1%) had decreases in HBV DNA of no less than 2 Log, 19 (59.4%) had HBeAg negative conversion, one (1.6%) had HBsAg negative conversion, and 110 patients (85.3%) had normal ALT levels (Table 2).

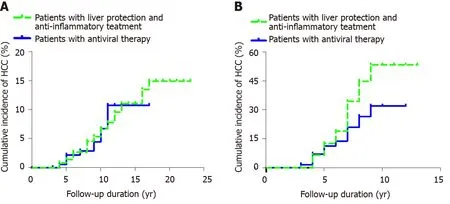

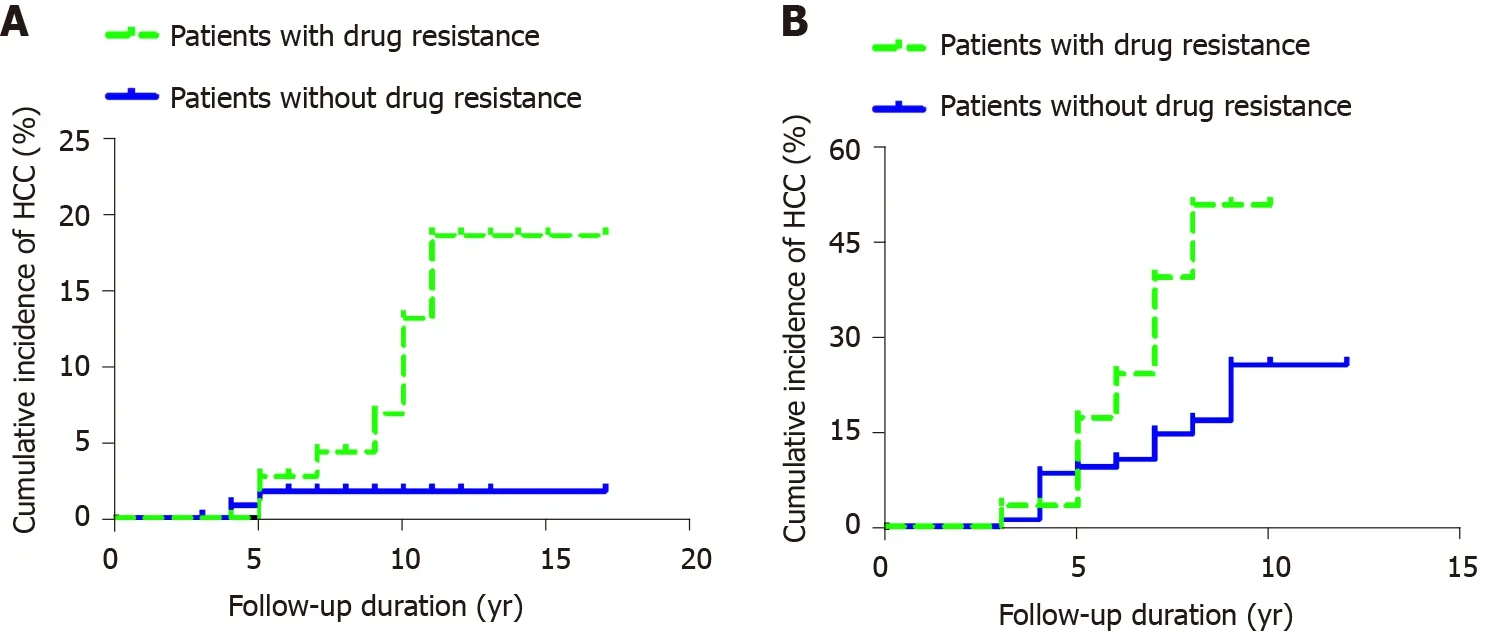

Comparison of cumulative incidence of HCC in CHB patients

Among 362 patients with CHB, the cumulative incidence rates of HCC (n = 29) in years 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16 and 18 were 0, 0.008, 0.027, 0.045, 0.067, 0.096, 0.111, 0.135 and 0.149, respectively. The cumulative incidence rates of HCC (n = 9) among the 203 patients in the control group in years 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14 and 16 were 0, 0.005, 0.022, 0.029, 0.066, 0.107, 0.107 and 0.107, respectively. After the Kaplan-Meier log-rank analysis, there was no significant difference in the cumulative incidence of HCC between the two groups (P = 0.842) (Figure 2A).

Comparison of cumulative incidence of HCC in patients with hepatitis B cirrhosis

Among the 96 patients with hepatitis B cirrhosis, the cumulative incidence rates of HCC (n = 27) in years 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 in the observation group were 0, 0.065, 0.189, 0.446 and 0.531, respectively. The cumulative incidence rates of HCC (n = 31) in years 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 and 14 among the 129 patients with cirrhosis were 0, 0.071, 0.138, 0.264, 0.319, 0.319 and 0.319, respectively. The incidence of HCC accumulation in the control group was lower than that in the observation group, and the results of the Kaplan–Meier log-rank analysis showed that there was a significant difference (P = 0.026) (Figure 2B).

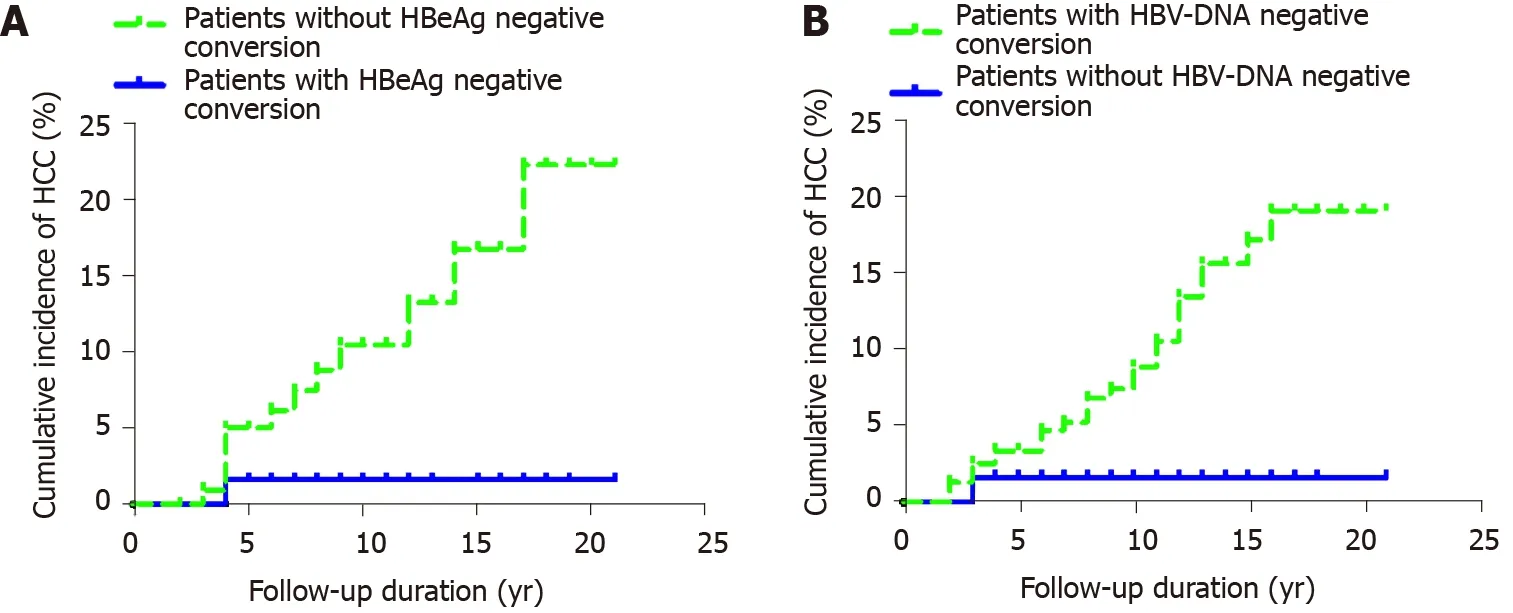

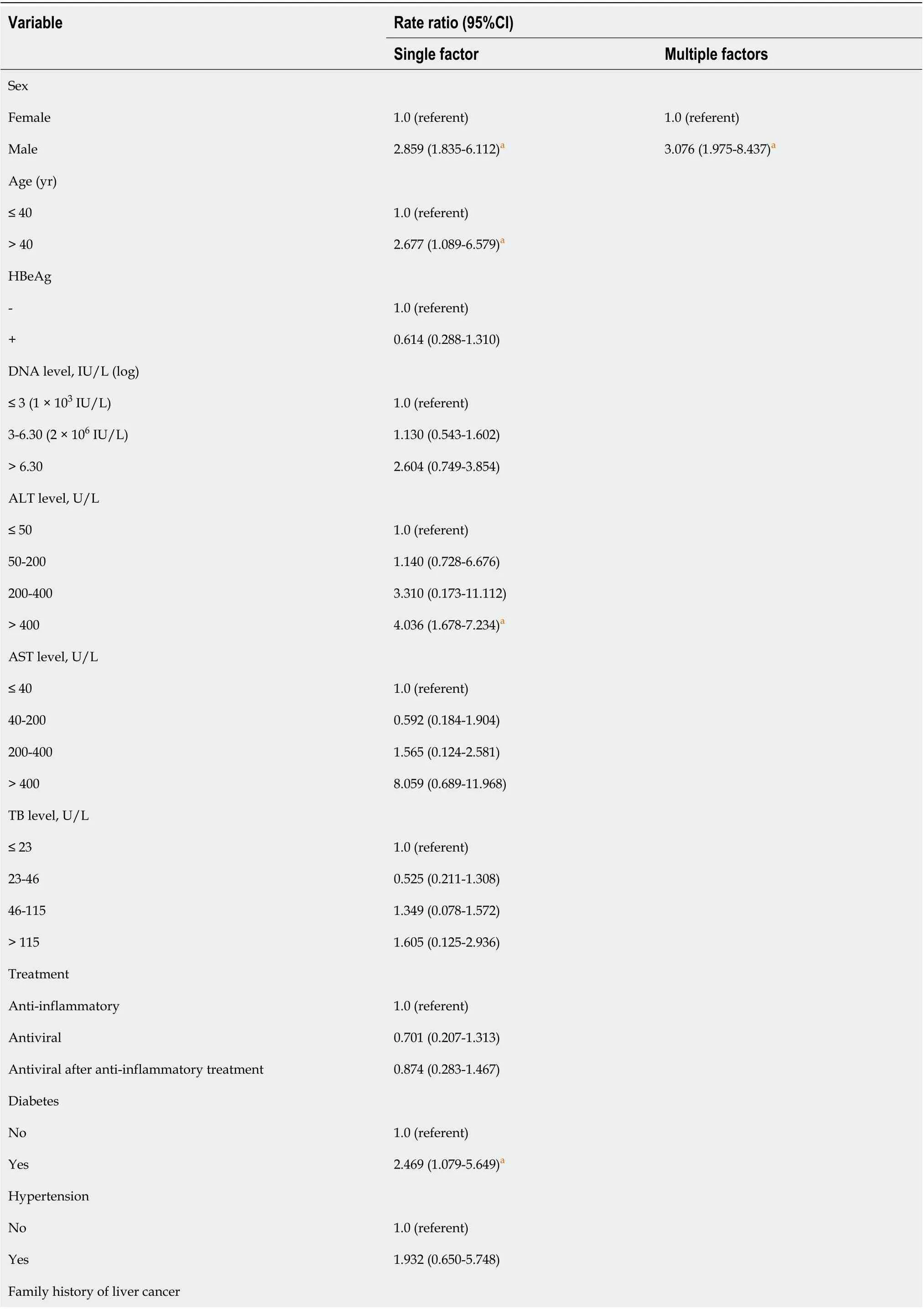

Cumulative incidence of HCC after HBeAg negative conversion in HBeAg-positive CHB patients

Among 362 patients with CHB, 198 were HBeAg positive, 65 had HBeAg negative conversion, and one developed HCC after HBeAg negative conversion. The cumulative incidence rates of HCC (n = 1) among the 65 patients in years 2, 4 and 6-20 were 0, 0.016 and 0.016-0.016, respectively. Among the 133 patients without HBeAg negative conversion, 12 developed HCC. The cumulative incidence rates of HCC (n = 12) in years 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14 and 16-20 were 0, 0.050, 0.062, 0.088, 0.104, 0.132, 0.167 and 0.223, respectively. The cumulative incidence rate of HCC in patients with CHB who did not have HBeAg negative conversion was higher than that in patients with HBeAg negative conversion. The cumulative incidence rates of HCC in the two groups were significantly different (P = 0.022) (Figure 3A).

Table 1 Data regarding the patients’ baseline characteristics

Table 2 Changes in hepatitis B virus-DNA, hepatitis B e antigen, hepatitis B surface antigen and alanine aminotransferase after antiinflammatory and hepatoprotective treatment and antiviral therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis B and cirrhosis, n (%)

Cumulative incidence of HCC after spontaneous decreases in HBV DNA to undetectable levels in patients with CHB

Among the 362 patients with CHB, 61 had undetectable HBV DNA, and one developed HCC after undetectable HBV DNA. The cumulative incidence rates of HCC (n = 1) in years 2 and 4-20 were 0.016 and 0.016, respectively. A total of 301 patients did not have undetectable HBV DNA, and 28 of them developed HCC. The cumulative incidence rates of liver cancer in years 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14 and 16-20 were 0.013, 0.034, 0.047, 0.068, 0.089, 0.135, 0.157 and 0.191, respectively. The incidence of HCC in patients without undetectable HBV DNA was higher than that of HCC in those with HBV-DNA negative conversion. There was no significant difference in the cumulative incidence of liver cancer between the two groups (P = 0.051) (Figure 3B).

Figure 2 Cumulative incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma. A: Comparison of the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma over time in two groups of chronic hepatitis B patients (patients with liver protection and anti-inflammatory treatment and patients with antiviral therapy); B: Comparison of the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma over time in patients with hepatitis B cirrhosis. HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

Figure 3 Cumulative incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma. A: Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatitis B e antigen negative conversion in hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B patients; B: Cumulative incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatitis B virus-DNA negative conversion in patients with chronic hepatitis B. HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; HBeAg: Hepatitis B e antigen; HBV: Hepatitis B virus.

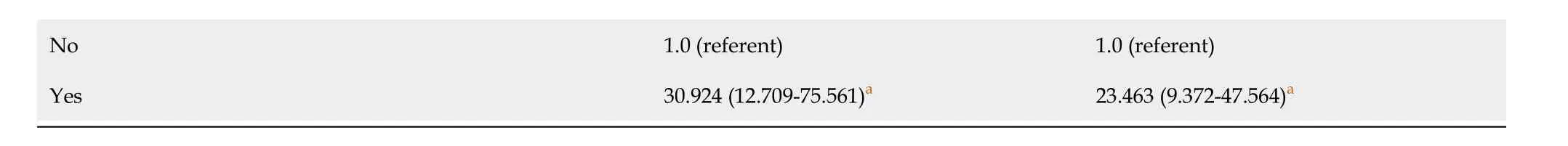

Cumulative incidence of HCC among patients with antiviral resistance in CHB

Among the 203 patients with CHB who received direct antiviral therapy, 79 developed antiviral resistance; of whom, 47 received LAM, 22 ADV, and 10 LDT. Seven of 79 patients developed HCC. The cumulative incidence rates of HCC among the 79 patients with drug resistance at years 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 were 0.000, 0.000, 0.027, 0.043, 0.130 and 0.185, respectively. The cumulative incidence rates of HCC (n = 2) among the 124 nonresistant patients at years 2, 4 and 6-12 were 0.000, 0.008 and 0.018, respectively. There was no significant difference in the cumulative incidence of HCC between the two groups according to the Kaplan-Meier log-rank test (P = 0.119) (Figure 4A).

Cumulative incidence of HCC in patients with antiviral resistance in hepatitis B cirrhosis

Of the 129 patients with direct antiviral cirrhosis, 30 developed antiviral resistance (HCC = 14); 17 of whom received LAM, eight ADV, and five LDT. The cumulative incidence rates of HCC among the 30 patients with drug resistance at years 2, 4, 6 and 8 were 0, 0.033, 0.240 and 0.506, respectively. The cumulative incidence rates of HCC (n = 16) among the 99 patients who did not develop antiviral resistance at years 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 were 0, 0.083, 0.105, 0.167 and 0.255, respectively. The cumulative incidence of HCC among patients with antiviral-resistant hepatitis B cirrhosis was higher than that among nonresistant patients. The difference was significantly different according to the Kaplan-Meier log-rank test (P = 0.004) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4 Cumulative incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma. A: Cumulative incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with antiviral resistance in chronic hepatitis B; B: Cumulative incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with antiviral resistance in hepatitis B cirrhosis. HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

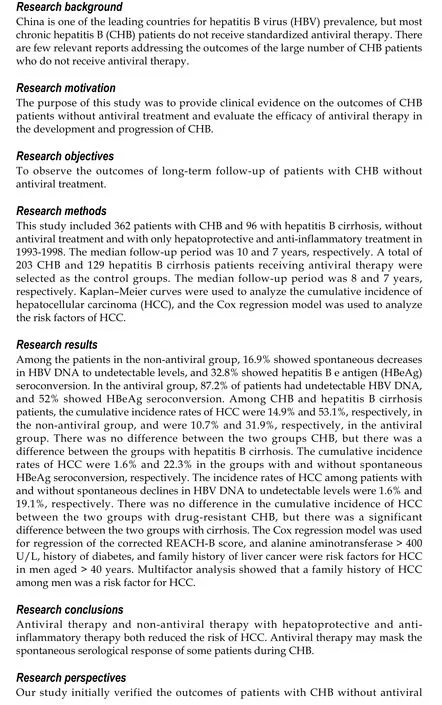

Cox regression analysis of risk factors for HCC in patients with CHB who were calibrated with REACH-B

We used the Cox regression model of the corrected REACH-B score to determine whether HCC occurred as the endpoint of observation, after adjusting for sex, age, HBeAg, ALT, AST, DNA, and other related parameters. The results showed that men aged > 40 years, ALT > 400 U/L, history of diabetes, and family history of HCC were risk factors for HCC (P < 0.05). Multivariate analysis showed that male sex and HCC family history were risk factors for HCC (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In China, HCC is mainly HBV-associated, and this form of HCC has a worse prognosis than hepatitis-C-virus-associated HCC. Therefore, the effect of antiviral therapy should be discussed based on the incidence of HBV-related HCC rather than on the disappearance of HBV viral markers or serological conversion as the main target of treatment.

The antiviral mechanism of nucleoside analogs (NAs) is propagated mainly through their inhibition of the polymerase of HBV replication, thereby controlling the HBV load in the serum and the circulating pool, thus reducing the pathogenic factors of HBV-related HCC[26]. However, NAs cannot completely eradicate covalently closed circular DNAs, and they cannot block the occurrence of HBV-related HCC. This is mainly related to the carcinogenic mechanism of HBV. It is generally believed that there are three factors contributing to HBV carcinogenesis: the integration of HBV and host genes; accumulation of HBX protein in cells; and the persistence of inflammation. HBV destroys the genes of host cells, and the trans-binding carcinogenesis of HBX proteins leads to a series of carcinogenic factors that cannot be countered by NA drugs. It is important to note that persistent liver inflammation is also an important factor in the development of HCC. The causes of HBV inflammation include: (1) Induction of the host immune response by HBV infection; and (2) Uncontrollable inflammatory factors. Specifically, under uncertain conditions, inflammation cannot change from an anti-infection/tissue damage mode to a balanced and stable state[26], leading to continuous progression of inflammation. Proinflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species produced in the process of inflammation lead to gene mutations or phenotypic modifications that promote canceration[27].

Antiviral therapy reduces HCC mainly by decreasing the HBV-DNA load, thereby reducing immune-related injury to the body[28-30]and the levels of carcinogenic factors associated with inflammation. NA antiviral therapy can effectively decrease the HBVDNA load, but it cannot achieve effective immune control. Immunoregulation is generally divided into positive and negative regulation. NA antiviral therapy mainly acts as a negative regulatory factor, but it does not affect positive regulatory factors; thus, it is difficult to achieve true immune functional recovery[31]. Therefore, 50%-70% of patients relapse after stopping drug treatment[32], which confirms the lack of immune recovery.

Current, relevant, long-term follow-up studies that have been published adopted aretrospective or database observation comparative design, but these studies all had many shortcomings regarding intergroup confounding factors[33]. The present study is a real-world clinical study, lasting 2-23 years, of CHB patients in China. The aim of the study was to evaluate the real clinical outcomes, particularly the occurrence of HCC, in patients who did not receive antiviral therapy but received only anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective therapy. Notably, a large number of data reported that it generally took 6-12 mo for HCC to be detected by B-ultrasound screening. In order to ensure the reliability and the objectivity of the results, we excluded patients with HCC occurring within 1 year of follow-up. We restricted the follow-up period to at least 2 years, and patients who developed detectable liver cancer within 1 year after enrollment were excluded. Considering that the time to find HCC takes 1-2 years, the follow-up period was determined to be ≥ 2 years. Our results showed that no patient in the CHB group and six patients in the cirrhosis group developed HCC within 1 year and we subsequently excluded these patients in the following observation.

Table 3 Cox regression analysis of risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B who were calibrated with REACH-B

aP < 0.05 vs the observation group. HBeAg: Hepatitis B e antigen; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; TB: Total bilirubin.

Our results showed that among 362 patients with CHB who were not treated with antiviral therapy but treated only with anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective therapy, after an average follow-up of 10 years, 16.9% had undetectable HBV DNA, 32.8% had HBeAg seroconversion, and 76.0% had ALT levels that returned to normal. Our results are similar to those of a previous study in Taiwan[34]. In addition, in the antiviral treatment group, 87.2% of patients were HBV-DNA negative, 52.0% had HBeAg seroconversion, and 94.1% had ALT levels that returned to normal. After antiviral treatment, the virological response of patients was significantly higher than that of patients without antiviral treatment; however, neither group showed significant differences.

At present, in China, anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective drugs, such as glycyrrhizin, glutathione, polyethylene phosphatidylcholine, silymarin, and dicyclol, are classified into multiple categories, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidative and antifibrotic drugs[35,36]. When patients first present with elevated ALT, over the following 5-10 years, approximately 17% of patients may have spontaneous decreases in HBV DNA to undetectable levels, and approximately 33% may have spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion. The results of our study showed that the cumulative incidence of HCC was significantly different between patients with and those without HBeAg seroconversion. As long as the liver inflammatory response is effectively controlled in such patients, once spontaneous HBeAg serological transformation occurs, immune control can be achieved, thereby leading to entry into the inactive HBsAg carrier period, stabilization of the disease for a long time, and a significant reduction of HCC[37]. Although antiviral therapy can significantly inhibit the replication of HBV DNA, 50%-70% of patients relapse after drug withdrawal; even when the serological conversion of HBeAg occurs, it is temporary and unstable, and the cumulative recurrence rate is 44% after a 4-year follow-up period following drug withdrawal[38]. Thus, although these relapsed patients achieve HBV-DNA negative conversion, they do not achieve true immune control, and only 30%-50% of patients have true immune control. There were no significant differences between patients with antiviral therapy who achieved true immune control and spontaneous seroconversion. Therefore, we suggest that antiviral therapy masks the spontaneous relief process of CHB. Several studies have confirmed that the incidence of HCC after interferon therapy is significantly lower than that in patients who benefit from NA antiviral therapy[39-42], which also demonstrates why patients with CHB without cirrhosis who benefit from NA antiviral therapy do not have the advantage of better prevention of HCC. The key is that anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective treatment can effectively improve the inflammatory response of the liver, slow down the progression of liver fibrosis during spontaneous seroconversion, and thus effectively reduce the incidence of HCC[43].

For patients with CHB complicated by cirrhosis, our results show that effective antiviral therapy can significantly reduce the cumulative incidence of HCC in patients with HBV-related cirrhosis. For hepatitis B cirrhosis patients who are positive for HBV DNA, taking antiviral therapy in a timely manner is important for controlling the persistent inflammatory response in the liver and eliminating the virus[44]. However, the cumulative incidence of HCC in patients with cirrhosis is still increasing with the prolongation of follow-up, and there is no plateau phase. This shows that antiviral therapy can only delay but not eliminate the occurrence of HCC. Notably, even if patients with cirrhosis are treated with antiviral drugs in a timely manner, the cumulative incidence of HCC is still higher than that of patients with CHB without liver cirrhosis. This indicates that cirrhosis remains the most important factor in the development of HCC[45].

Drug resistance is common in CHB patients receiving antiviral therapy, especially in those treated with LAM and ADV in the early stage. However, will the incidence of HCC be further increased in patients with antiviral resistance? At present, there are still few reports suggesting that drug resistance may offset the benefit of antiviral therapy in patients with cirrhosis[46]. The results of our study showed that there was no significant difference in the cumulative incidence of drug-resistant and nonresistant HCC after antiviral therapy in patients with CHB without cirrhosis. This finding may be related to effective control of the HBV-DNA load in these patients with a low risk of HCC through timely rescue treatment, even when drug resistance occurred. However, in patients with cirrhosis, the incidence of HCC in drug-resistant patients was significantly higher than that in nonresistant patients, and the difference was significantly different. For patients with cirrhosis, the reserve function of the liver decreases, and the effective liver tissue decreases; drug resistance can lead to virological breakthroughs or rebounds, accelerate the progression of the disease, and further aggravate liver injury, thus increasing the risk of cirrhosis and HCC[47]. HBV mutation tends to increase gradually with infection time and disease progression[48], and the selection of antiviral drugs with high resistance barriers is an important factor in preventing viral mutation and reducing the occurrence of HCC in patients with liver cirrhosis.

Taiwanese scholars used data from the Reveal-HBV cohort to quantify HCC risk factors, and they established and preliminarily verified the first HBV-related HCC prediction model, REACH-B. The HCC scoring system includes host factors such as sex, age, family history of HCC, serum ALT levels, and virological indicators such as HBeAg levels, HBV-DNA levels, HBsAg quantification, and HBV genotypes[49]. The optimal cutoff point is 8 points, which is more suitable for the Asian population. Many guidelines recommend this model. The higher the score of this model, the higher the incidence of HCC. In this study, the REACH-B score did not indicate that non-antiviral therapy was an independent factor in the occurrence of HCC, while the occurrence of HCC was closely related to age, sex and family history of HCC.

This study was a single-center, pre-retrospective study, and further prospective cohort studies will be conducted when patients are identified as research subjects. Because antiviral therapy patients were enrolled after 2001 and the enrollment time of each group was different, the results of the study were biased to some extent. In this study, LAM, ADV and other high-resistance and low-potency drugs were used in the early stage of antiviral therapy, which affected the effectiveness of antiviral therapy. The evaluation criteria of the patients with liver cirrhosis were mainly based on Bmode ultrasound, while only 10% of patients were assessed by histopathology, which may have led to an underestimation in diagnosing the degree of liver fibrosis and early cirrhosis.

This study shows that in addition to viruses being the main carcinogenic factor in patients with CHB, inflammation or uncontrollable inflammation of the liver are important carcinogenic factors. Whether it is antiviral therapy or anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective therapy alone, controlling liver inflammation is one of the mechanisms for improving liver histology. Therefore, once ALT elevation occurs in patients with CHB without cirrhosis, as long as liver inflammation is effectively controlled and immune control is achieved, the incidence of long-term HCC can be reduced to a certain extent. Our results showed that patients with liver cirrhosis had a higher cumulative incidence of HCC, so it was important to prevent patients developing cirrhosis. Patients with cirrhosis must receive antiviral therapy. Antiviral therapy can be implemented at the stage of progressive liver fibrosis to prevent the rapid occurrence of cirrhosis, which will be beneficial to the long-term prevention of HCC. Early NA antiviral therapy for low-HCC-risk patients with CHB without cirrhosis may mask the spontaneous serological response of some patients; therefore, the role of early antiviral therapy in reducing the occurrence of HCC cannot be overestimated.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, antiviral therapy and non-antiviral therapy with liver protection and anti-inflammatory therapy can reduce the risk of HCC. Antiviral therapy may mask the spontaneous serological response of some patients during CHB. Therefore, the effect of early antiviral therapy on reducing the incidence of HCC cannot be overestimated.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

World Journal of Gastroenterology2021年11期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2021年11期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Fatigue in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in Eastern China

- Prospective single-blinded single-center randomized controlled trial of Prep Kit-C and Moviprep: Does underlying inflammatory bowel disease impact tolerability and efficacy?

- Apolipoprotein E polymorphism influences orthotopic liver transplantation outcomes in patients with hepatitis C virus-induced liver cirrhosis

- Study on the characteristics of intestinal motility of constipation in patients with Parkinson's disease

- Efficacy and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric tube cancer: A multicenter retrospective study

- How to manage inflammatory bowel disease during the COVID-19 pandemic: A guide for the practicing clinician